An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Fitz Henry Lane: Painting, Science, & Owl's Head

An Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2016)

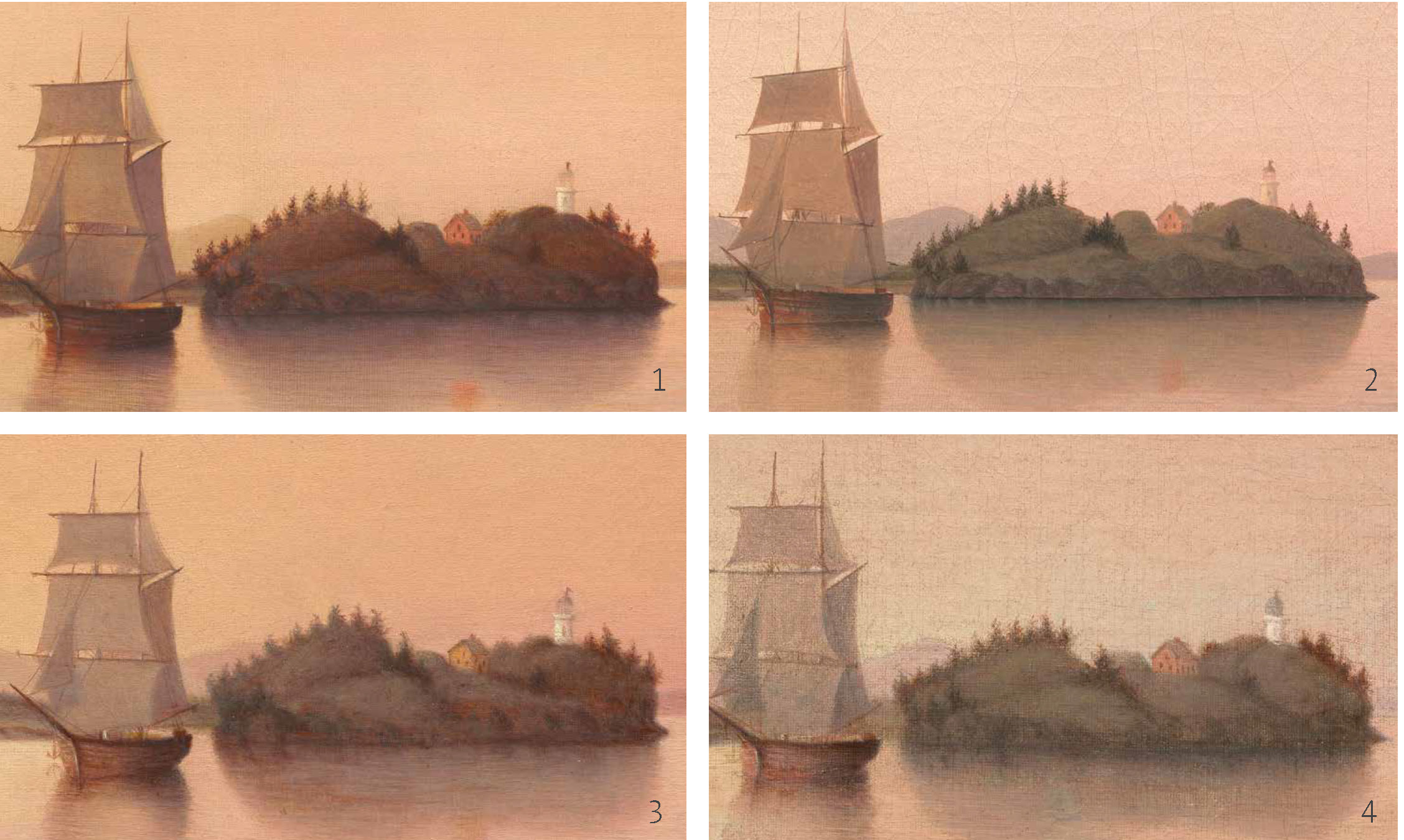

Fitz Henry Lane's Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862 (inv. 47) has long been a highlight of the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, celebrated for the quiet beauty of its luminous light and color– a masterpiece of mid-nineteenth-century American landscape painting. Surprisingly, three more versions have surfaced. All four paintings are extremely close in size and composition. What could this mean?

|

Mary Blood Mellen, Owl's Head, 1860s (not published) Isaacson Family Trust

|

Fitz Henry Lane, Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862 (inv. 47) |

|

Mary Blood Mellen, Owl's Head, 1860s (not published) Private Collection |

|

Lane had a talented student, Mary Blood Mellen, who seemingly copied many of his compositions. But the working relationship between Lane and Mellen appears to have been more complex than a student merely copying a master’s work. By the 1850s, Mellen was an apprentice in Lane's Gloucester studio, where, as part of her training, she spent time copying her teacher's work. She was apparently so skilled at the task that on one occasion when two paintings were hung side-by-side Lane reportedly even had trouble telling his canvas from hers. The two were evidently collaborators as well– Coast of Maine, 1850s (inv. 32) at the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, bears both artists' signatures.

Close examination shows that the “copies” vary in technique, and MFA curators and conservators are actively investigating whether Lane himself may have worked on them as well. An 2016 installation at the MFA (as summarized here) featured research on the artists’ working methods and presented the findings to date.

Inscriptions

Fitz Henry Lane, Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862 (inv. 47)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865, 1948 48.448

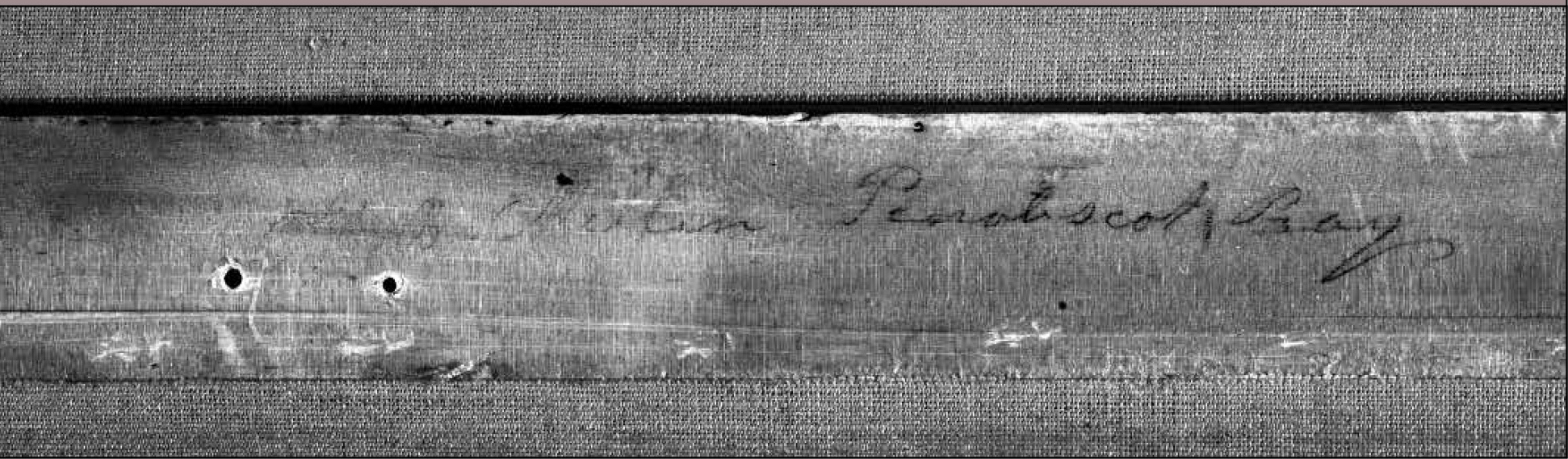

On the back of the painting above, an inscription in Lane's hand establishes it as his own work: Owl's Head–Penobscot Bay, by F.H. Lane, 1862. The text is no longer visible, however – it was covered up by a canvas lining, which was attached to the back of the painting during the 20th century. Knowing it was there, conservators were able to take a photograph of the inscription from the front, using infrared technology. This inscription established a baseline for comparison of all four Owl's Head paintings.

|

|

|

|

|

1. An inscription on the reverse, on a stretcher bar, is only visible using an infrared camera. It reads: Mary B. Mellen Penobscot Bay. |

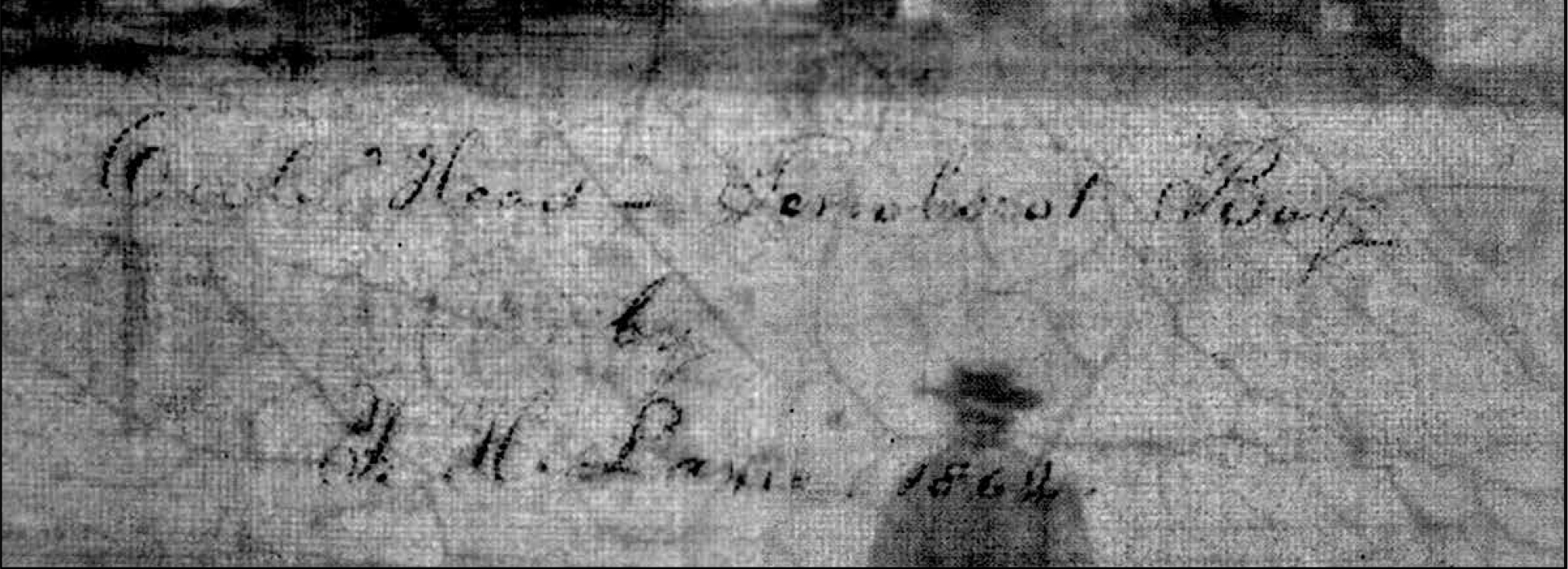

2. Infrared image of the painting's title and Lane's signature, Owl's Head–Penobscot Bay, by F.H. Lane, 1862 taken from the front. |

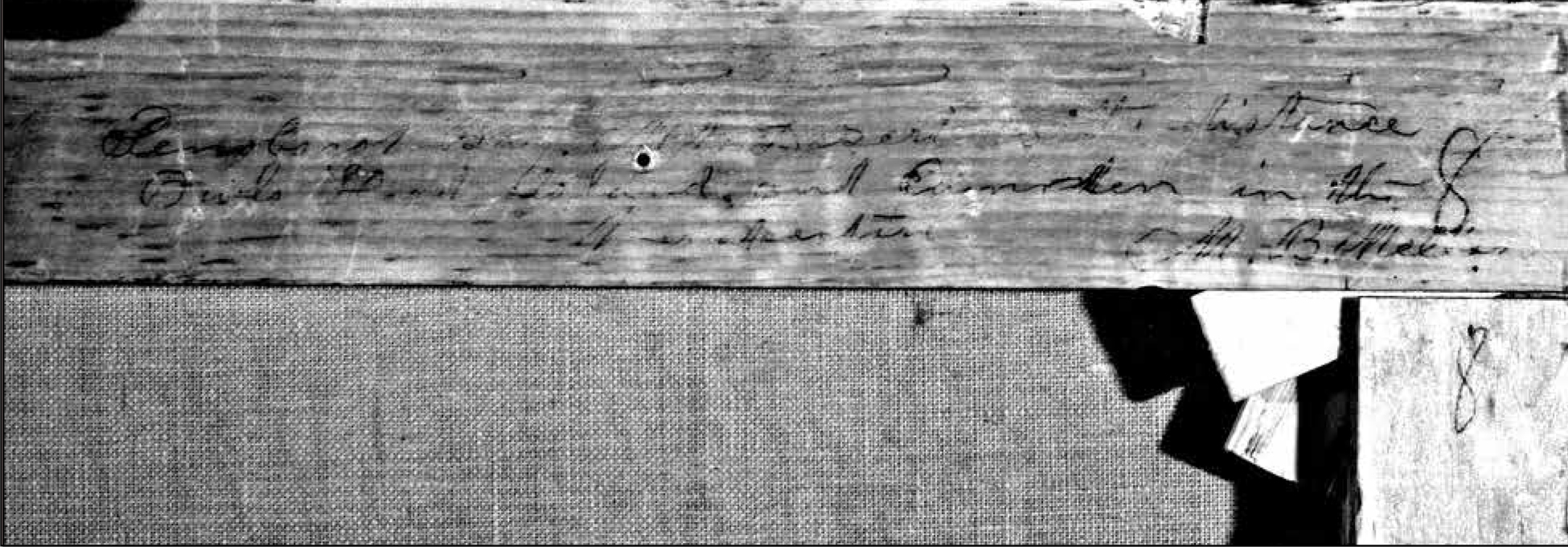

3. An infrared camera revealed this painting's inscription, on the stretcher bar on the reverse: Penobscot Bay Mt. Desert in the distance/ Owl's Head Island and Camden in the distance/ M.B. Mellen. |

4. At some point in its history, this painting was removed from its stretcher and attached to a board. The original stretcher–and any inscriptions thereupon – have been lost. |

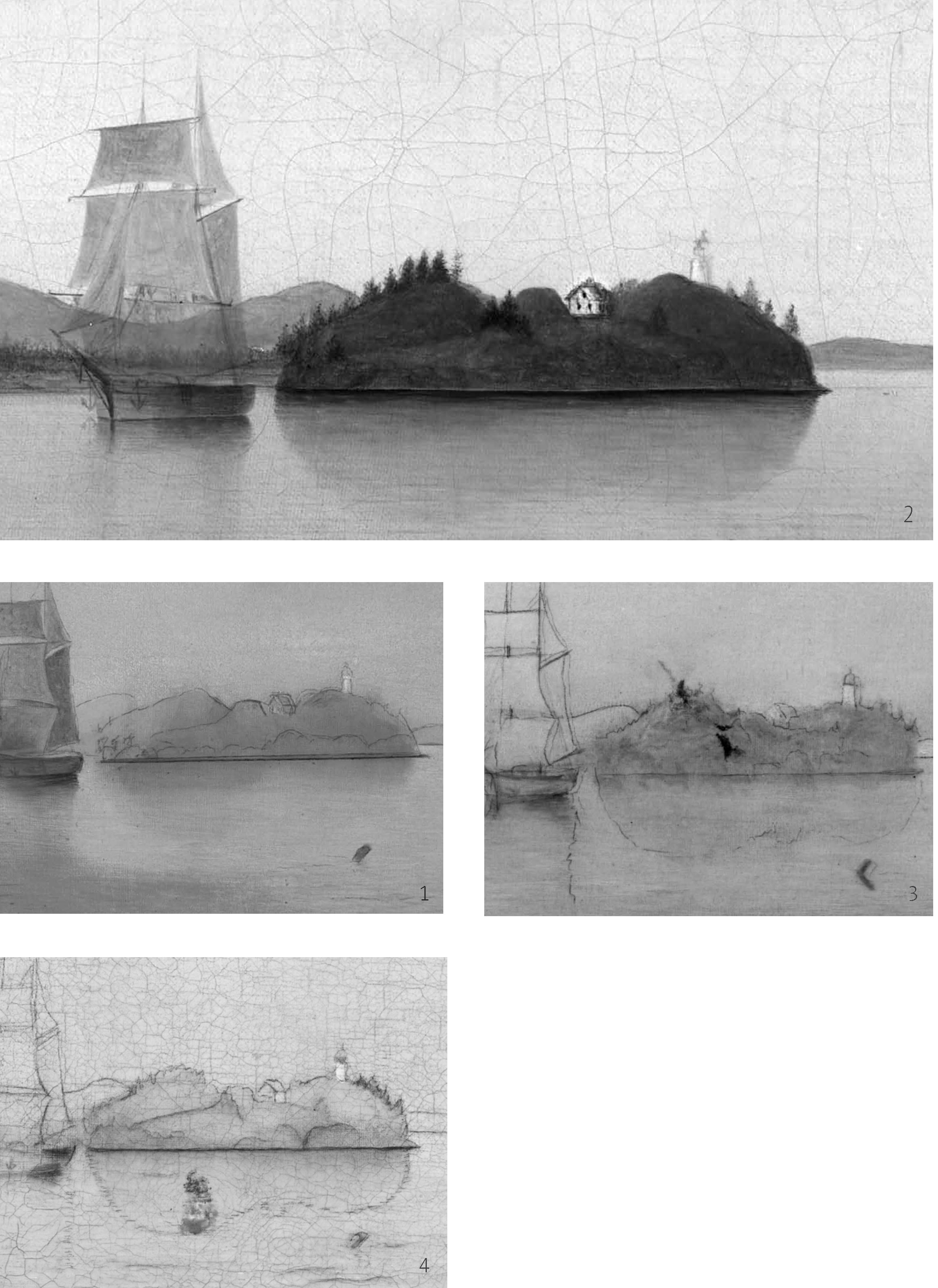

Infrared ReflectographyConservators use a number of imaging techniques to study an artist’s materials and techniques. Examining a painting using infrared wavelengths (longer than visible light wavelengths) can yield information about layers beneath the surface that are not visible to the naked eye. The absorption of infrared wavelengths varies for different pigments and materials; under certain circumstances, underdrawing or compositional changes made by the artist are revealed. Conservators examined all four Owl’s Head paintings using infrared reflectography, which can penetrate the layers of paint and reflect back darker mediums such as graphite, ink, or even darker oil paint. In each case, the infrared camera revealed underdrawings that the artist sketched onto the surface of the canvas as a compositional guide. Note the drawing on the hills and buildings in the MFA painting by Lane (#2), but there are no underdrawings for transient elements such as reflections or waves. In the other three, these details are sketched in. Since these elements are also missing from the original drawing, this indicates that Mellen likely based her underdrawings on Lane’s finished painting. Given how close the composition of each of these three works is to the Lane, it seems likely that a camera lucida was used to transfer the Lane composition to the canvases. |

|

Paint and Color

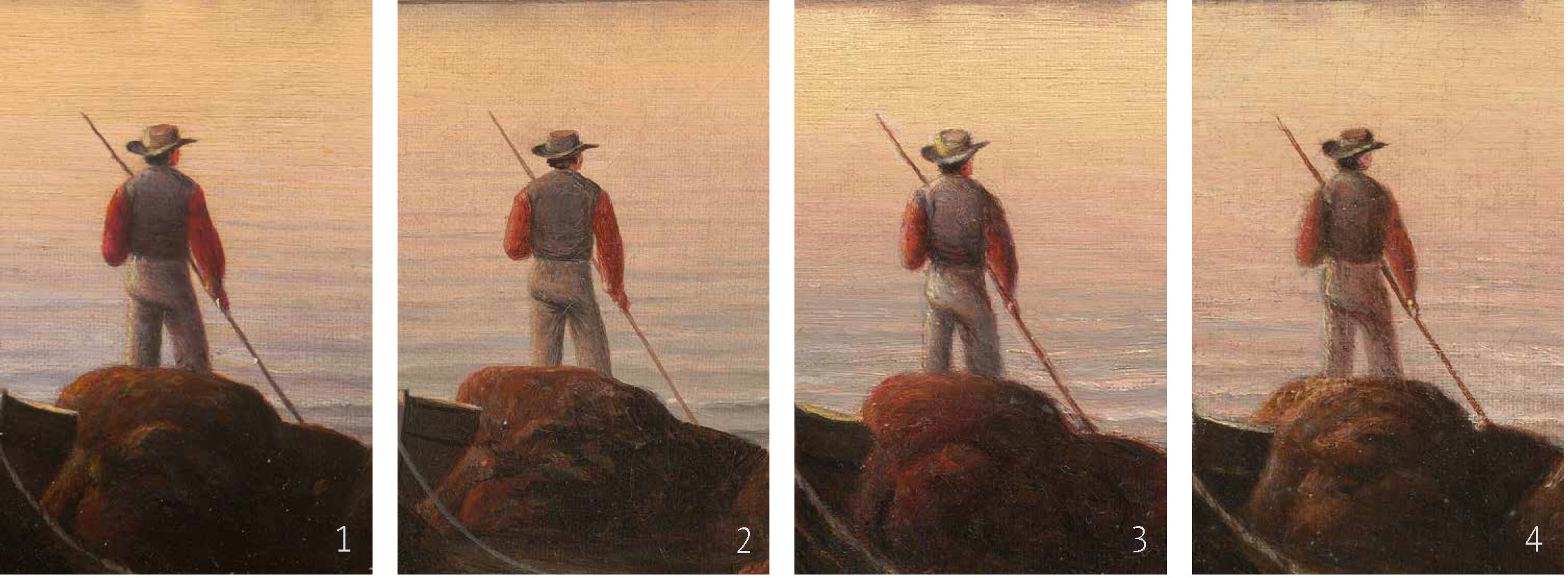

MFA curators and conservators also compared paint application and the use of color in the four paintings. In general, Lane's brushstrokes seem crisper, and he more precisely defines compositional elements such as the pine trees (image 2 in both above and below images.) Lane's palette is also cooler than Mellen's. Yet careful examination reveals that these details can sometimes be too close to definitively separate the authorship. It is entirely possible that, in studio tradition, Lane contributed to Mellen's paintings, even if she signed them, and this complicates the issues of attribution even further.

Fitz Henry Lane and the Camera Lucida

As early as 1849, Lane was hailed in a Gloucester newspaper for a painting “flooded with rosy and golden light.” At the same time, the writer noted that Lane rendered the details of each natural and manmade landmark with unerring precision and topographical accuracy. This marriage of science and art characterized Lane’s paintings throughout his career, and has been the focus of a research project related to the study of Lane and Mellen.

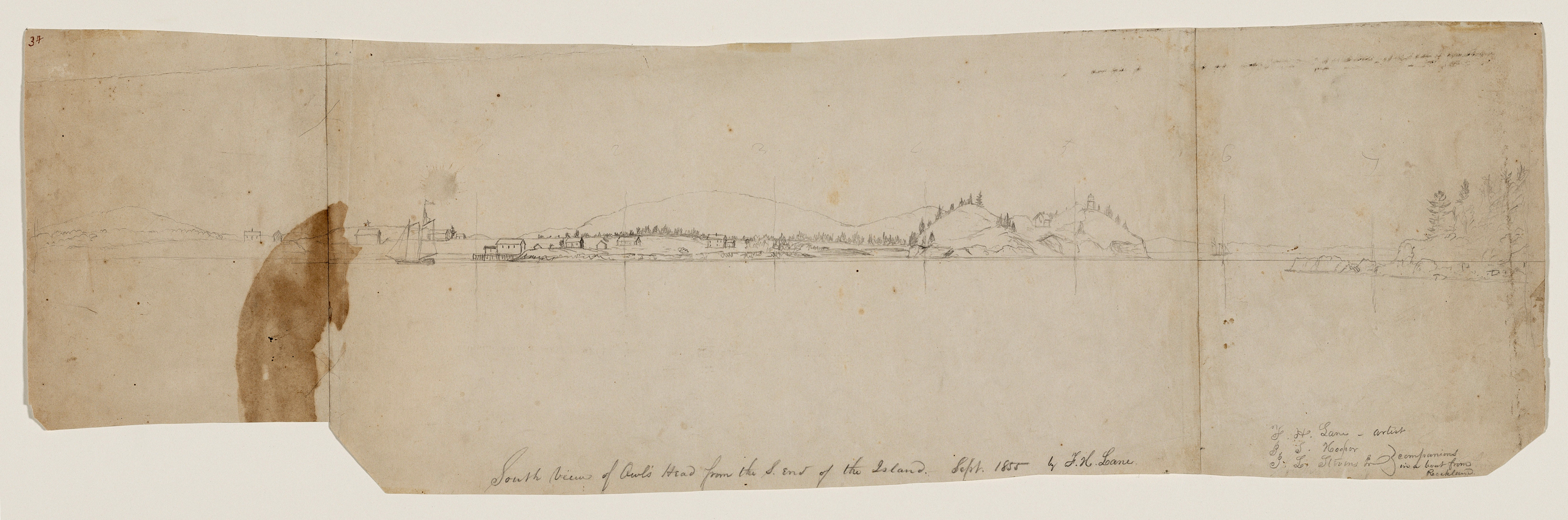

Fitz Henry Lane, South View of Owl's Head, from the S. End of the Island, 1855 (inv. 128)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

Lane based the composition of South View of Owl's Head, from the S. End of the Island, 1855 (inv. 128) on a drawing, and he likely transferred the composition of the drawing to the canvas with the help of a camera lucida.

To create his topographical sketches, Lane likely used some kind of drawing tool. Though no documentation survives, a variety of such instruments would have been available– the most likely among them being the camera lucida.

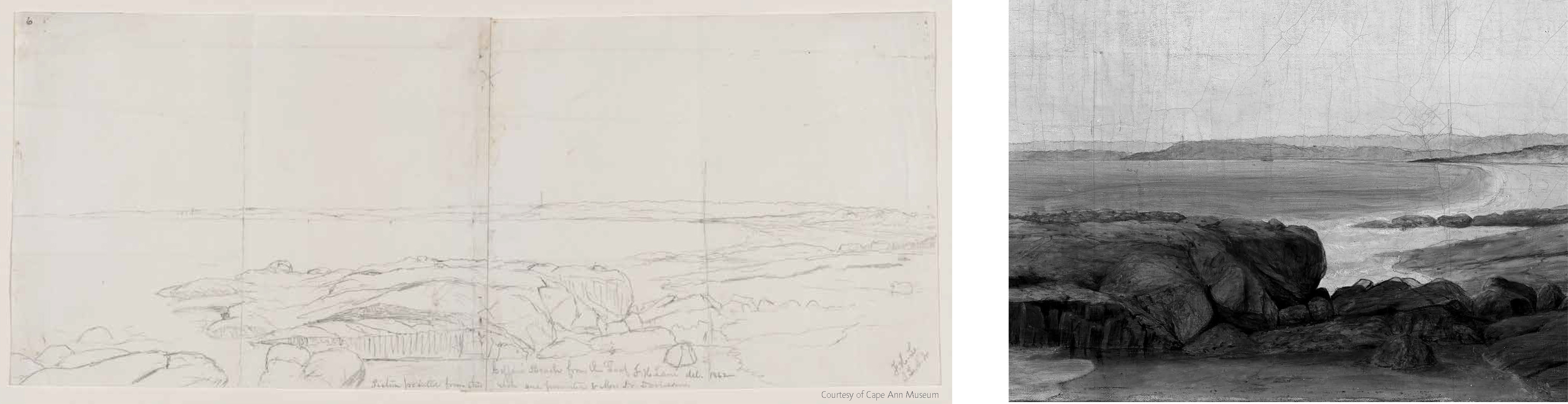

Lane's sketch of Gloucester's Coffin's Beach, made from a rocky outcropping at the northern end of the beach. It's possible Lane used a camera lucida to capture the scene, and to transfer his sketch to the canvas in preparation for painting. The vertical lines in the sketch and in the infrared reflectogram of the painting at right would have helped him line up the lens in the camera for an undistorted transfer section to section.

What makes us think he used a camera lucida? Close looking at Lane's drawings reveals two distinct drawing styles: one spontaneous and fluid, the other more static and uniform. In his sketch of Gloucester's Coffin's Beach, Lane employed both methods in a single drawing. The former approach, with lines that very in pressure, length, and width, would seem to indicated a freehand technique, seen in the shadows on the rocks in the foreground. In the latter method, visible in the contours of the land and rocks, regular lines are consistent in strength and have the mechanical, stop-and-start quality that suggests the use of an optical device.

Fitz Henry Lane, View of Coffin's Beach, 1862 (inv. 41)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Mrs. Barclay Tilton in memory of Dr. Herman E. Davidson, 1953 53.383

While the finished painting replicates the outlines of the drawing, Lane widened the composition, accentuating the horizontal format and emphasizing the expansiveness of the landscape and a sense of emptiness. Lane's subtle blending of the glowing pink-to-blue of the early morning sky transforms a topographical study into one of his finest landscapes.

Working with a Camera Lucida

Invented in England in 1806, the camera lucida ("light room" in Latin) features a prism and lens attached to a flexible metal arm, which can be clamped onto a table or board. To use it, an artist would point the prism toward a desired scene, place a piece of paper on the surface below the lens, and carefully position his or her eye to look through the lens toward the paper. The scene to be drawn–cast through the prism and the lens– would appear superimposed on the paper, making it possible to create an accurate tracing. It could also be used for transferring an image to another surface, for example from a drawing to canvas.

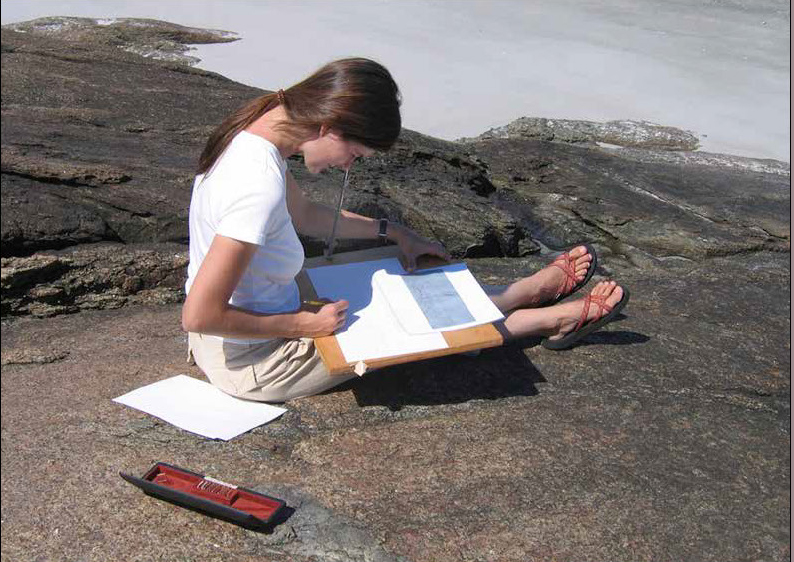

Painting conservator Sandy Kelberlau using the camera lucida to sketch View of Coffin's Beach.