An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

inv. 35

Portrait of the "National Eagle"

Ship "National Eagle"

1853 Oil on canvas 23 1/2 x 36 in. (59.7 x 91.4 cm) Signed and dated lower right: F H Lane 1853

|

Supplementary Images

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

Oil on canvas

23 1/2 x 36 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of the Estate of Marjory A. Johnson, 1988 (2612.00)

Detail from Lane's painting of the "National Eagle" showing a pilot schooner with pilot being rowed to the ship.

Filed under: Schooner (Pilot) »

The medium clipper ship "National Eagle," 1095 tons, was built by Joshua T. Foster at Medford for Fisher and Company, Boston in 1852.

– Erik Ronnberg

When inbound merchant ships approached their destination ports, they were required by law to pick up a pilot to guide the vessel safely into the harbor. Pilot schooners were stationed outside the ports to transfer one of their pilots to the incoming ship by means of a small rowing boat designed for this task, even in heavy seas. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, this boat was called a canoe. In other ports, such as New York, they were of different design and called yawls. (1)

In hull form, the pilot canoe bore no resemblance to any Native American watercraft by that name. The term’s origin seems to be French, where a canot was a small, beamy, and very seaworthy rowing boat. A bilingual guide to French nautical terms and their English equivalents contains a sample dialogue between a shipmaster and a pilot wherein the term canot is used for the pilot’s boat. (2) Definitions and descriptions of the French canot as a ship's boat used for communication between vessels and between ship and shore support the French origin for the Boston pilots' term "canoe." (3) Pilot yawls, as built and used in New York, closely resembled Whitehall boats in design, though with variations in construction. (4)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Charles I. Lampee, “Memories of Cruises on Boston Pilot Boats of Long Ago,” Nautical Research Journal 10, no. 2: 44–58.

2. Eugène Pornain, Termes Nautiques (Sea Terms) Anglais Francais, 13th ed. (Paris: Augustin Challamel,1890), 181–83.

3. John Harland, Seamanship in the Age of Sail (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1984), 283–84; and Lecomte, Jules, Dictionnaire Pittoresque de Marine (Paris: 1835; Douarnenez: Editions de L'estran, 1982), see "canot."

4. Erik A.R. Ronnberg, Jr., “Boston Pilot Canoes Revisited,” Nautical Research Journal 39, no. 3: 166.

Oil on canvas

23 1/2 x 36 in. (59.7 x 91.4 cm)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of the Estate of Marjory A. Johnson, 1988 (2612.00)

In this detail, the canoe can just be discerned conveying the pilot from the pilot boat to the clipper ship.

Pilot schooners in the pre-Civil War period were small- to medium-size schooners (60 to 90 feet on deck) which transported pilots to inbound vessels and picked up pilots from outbound vessels. Their presence was indicated by a signal flag hoisted on the main mast. In Boston, the pilot flag was blue and white, divided vertically. In New York, the flag was solid blue, sometimes with stars in rows. Other ports had pilot flags of differing designs.

When a merchant ship approached its destination port, it was (and still is) mandated by law to take on a pilot to guide the ship through unfamiliar channels, tidal currents, and other hazards to reach safe anchorage or berthing. The same law applies to outbound ships, which must take on a pilot to guide the vessel safely, leaving the pilot with a stationed pilot schooner once the port is cleared. The small rowing boat used to transfer the pilot from schooner to ship (or ship to schooner) was called a pilot yawl (in New York) or a pilot canoe (in Boston).

In many American ports, piloting could be a very competitive business, with rival schooners racing to an inbound ship to be first to put a pilot on board. These vessels were sometimes sold out of service to become yachts, while yachts were occasionally sold into pilot service, so adapted for speed were both types.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

Tom Cunliff, Pilots 1: Pilot Schooners of North America and Great Britain (Douarnenez, France: Le Chasse-Maree/Maritime Life and Traditions; and Brooklin, ME: Wooden Boat, 2001).

Photograph

Johnson, H. and Lightfoot, F.S.: Maritime New York in Nineteenth-Century Photographs, Dover Publications, Inc., New York

The New York pilot boats would sail out to meet large incoming ships, flying the blue and white flag. The pilot would board the large ship and guide her into harbor. On outgoing trips the pilot boat would pick up the pilot after the ship in his charge had cleared the harbor.

Also filed under: New York Harbor »

Mahogany, cotton, paper, metal

29 x 34 x 6 1/2 in (73.66 x 86.36 x 16.51 cm)

M27746

Peabody Essex Museum

Also filed under: Ship Models »

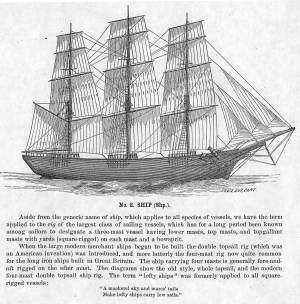

The term "ship," as used by nineteenth-century merchants and seamen, referred to a large three-masted sailing vessel which was square-rigged on all three masts. (1) In that same period, sailing warships of the largest classes were also called ships, or more formally, ships of the line, their size qualifying them to engage the enemy in a line of battle. (2) In the second half of the nineteenth century, as sailing vessels were replaced by engine-powered vessels, the term ship was applied to any large vessel, regardless of propulsion or use. (3)

Ships were often further defined by their specialized uses or modifications, clipper ships and packet ships being the most noted examples. Built for speed, clipper ships were employed in carrying high-value or perishable goods over long distances. (4) Lane painted formal portraits of clipper ships for their owners, as well as generic examples for his port paintings. (5)

Packet ships were designed for carrying capacity which required some sacrifice in speed while still being able to make scheduled passages within a reasonable time frame between regular destinations. In the packet trade with European ports, mail, passengers, and bulk cargos such as cotton, textiles, and farm produce made the eastward passages. Mail, passengers (usually in much larger numbers), and finished wares were the usual cargos for return trips. (6) Lane depicted these vessels in portraits for their owners, and in his port scenes of Boston and New York Harbors.

Ships in specific trades were often identified by their cargos: salt ships which brought salt to Gloucester for curing dried fish; tea clippers in the China Trade; coffee ships in the West Indies and South American trades, and cotton ships bringing cotton to mills in New England or to European ports. Some trades were identified by the special destination of a ship’s regular voyages; hence Gloucester vessels in the trade with Surinam were identified as Surinam ships (or barks, or brigs, depending on their rigs). In Lane’s Gloucester Harbor scenes, there are likely (though not identifiable) examples of Surinam ships, but only the ship "California" in his depiction of the Burnham marine railway in Gloucester (see Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, 1857 (inv. 29)) is so identified. (7)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. R[ichard)] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman’s Friend, 13th ed. (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1873), p. 121 and Plate IV with captions.

2. A Naval Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884), 739, 741.

3. M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World’s Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 536.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 281–87.

5. Ibid.

6. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 26–30.

7. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 67–69.

Photograph

From American Clipper Ships 1833–1858, by Octavius T. Howe and Frederick C. Matthews, vol. 1 (Salem, MA: Marine Research Society, 1926).

Photo caption reads: "'Golden State' 1363 tons, built at New York, in 1852. From a photograph showing her in dock at Quebec in 1884."

Also filed under: "Golden State" (Clipper Ship) »

Oil on canvas

24 x 35 in.

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

Walters' painting depicts the "Nonantum" homeward bound for Boston from Liverpool in 1842. The paddle-steamer is one of the four Clyde-built Britannia-class vessels, of which one is visible crossing in the opposite direction.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Packet Shipping » // Walters, Samuel »

The ensign of the United States refers to the flag of the United States when used as a maritime flag to indentify nationality. As required on entering port, a vessel would fly her own ensign at the stern, but a conventional token of respect to the host country would be to fly the flag of the host country (the United States in Boston Harbor, for example) at the foremast. See The "Britannia" Entering Boston Harbor, 1848 (inv. 49) for an example of a ship doing this. The American ensign often had the stars in the canton arranged in a circle with one large star in the center; an alternative on merchant ensigns was star-shaped constellation. In times of distress a ship would fly the ensign upside down, as can be seen in Wreck of the Roma, 1846 (inv. 250).

The use of flags on vessels is different from the use of flags on land. The importance and history of the flagpole in Fresh Water Cove in Gloucester is still being studied.

The modern meaning of the flag was forged in December 1860, when Major Robert Anderson moved the U.S. garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Adam Goodheart argues this was the opening move of the American Civil War, and the flag was used throughout northern states to symbolize American nationalism and rejection of secessionism.

Before that day, the flag had served mostly as a military ensign or a convenient marking of American territory, flown from forts, embassies, and ships, and displayed on special occasions like American Independence day. But in the weeks after Major Anderson's surprising stand, it became something different. Suddenly the Stars and Stripes flew—as it does today, and especially as it did after the September 11 attacks in 2001—from houses, from storefronts, from churches; above the village greens and college quads. For the first time American flags were mass-produced rather than individually stitched and even so, manufacturers could not keep up with demand. As the long winter of 1861 turned into spring, that old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union cause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for.

– Adam Goodheart, Prologue of 1861: The Civil War Awakening (2011).

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

A view of a Cove on the western side of Gloucester Harbor, with the landing at Brookbank. Houses are seen in the woods back. A boat with two men is in the foreground.

Also filed under: Brookbank » // Fresh Water Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854 CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

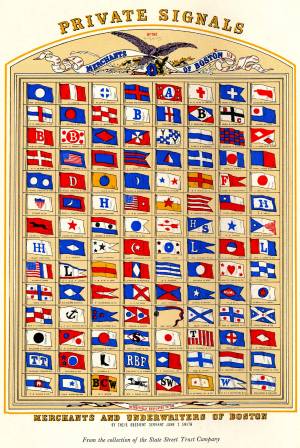

The use of signal flags, for ship-to-ship communication, generally preceded land-based chains of maritime semaphore stations, the latter using flags or rotating arms, until the advent of the electric or magnetic telegraph.

Until the end of the Napoleonic wars, merchant ships generally sailed in convoy as ordered by the escorting warship(s) using a few simple flags. Peace brought independent voyaging, the end of the convoy system, and the realization by various authorities that merchant vessels now needed their own separate means of signaling to each other. This resulted in a handful of rival codes, each with its individual flags and syntax. In general, they each had a section enabling ship identification and also a "vocabulary" section for transmitting selected messages. It was not until 1857 that a common Commercial Code became available for international use, only gradually replacing the earlier ones. All existed side by side for a decade or two.

Signal systems for American ships were originally intended to identify a vessel by name and owner; only later were more advanced systems developed to convey messages. Most basic were private signals, or "house flags", each of a different design or pattern, identifying the vessel's owner; identification charts were local and poorly distributed, limiting their usefulness. A secondary signal, a flag or large pennant bearing the vessel's name, was sometimes flown by larger ships, but pictorial records of them are uncommon. These private signal flags usually flew from the foremasthead or main masthead if a three master ship. Pilot boats had their own identifying flags, blue and white as seen in Spitfire Entering Boston Harbor (inv. 536). Small vessels, such as schooners, often had a "tell-tale" pennant, an often-unmarked and often red flag, that was used to determine wind direction.

A numerical code flag system, identifying vessels by the code numbers, was introduced by Captain Frederick Marryat R.N. in 1817 for English vessels. American vessels soon adopted this system. Elford's "marine telegraphic system" was the first American equivalent to the Marryat code flags, first issued in 1823, and with changes, remaining in use until the late 1850s. Most of the signal flags on vessels depicted by Lane use Elford's; Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43) is a noteworthy example of his depiction of Marryat's. The Elford's Code was popular in America on account of its simplicity and only required six blue and white flags. Eventually these changed to red and white, although it is unclear exactly when this happened. Instructions and a key ot the Elford's Code's use are included in successive editions of the Boston Harbor Signal Book.

Whereas the other codes employ at least ten flags of diverse shapes and colours, there are only six Elford flags in total, representing the numbers one to six. All are uniformly rectangular and monochrome in colour (either blue and white or red and white—or even black and white as in an early photograph). Selected from these six flags each individual vessel is allotted a combination of four flags to be prominently displayed as a vertical hoist. Reading from above down these convey its "designated number." Armed with this number and the type of vessel (e.g. ship, bark, brig, schooner /or steamer) the subject can be uniquely identified by reference to a copy of the Boston Harbor Signal Book for the appropriate year.

– A. Sam Davidson

As reproduced in Yankee Sailing Ship Cards by Allan Forbes and Ralph M. Eastman (Boston: State Street Trust Company, 1948).

Also filed under: "Eastern Star" (Bark) » // Forbes, Robert Bennet »

Harvard Depository: Widener (NAV 578.57)

For digitized version, click here.

Also filed under: Boston Harbor »

Boston: Eastburn's Press

New York Public Library

Complete book is included in Google Books, click here.

In The American Neptune 3, no. 3 (July 1943): 205–21.

Peabody Essex Museum

Descriptions of Marryat, Elford, Rogers, and commercial code signal systems, and private signals. Includes illustrations of flag systems with color keys.

Vessel ornamentation assumed two forms: carvings and color schemes. Carvings, or "ship carvings," as they are called by maritime scholars, are usually crafted in wood and painted or gilt. Many vessels were too small or their owners too frugal to permit carved embellishments, in which cases the enhancement of the vessel's color scheme was a practical alternative. This can be seen in many of the coastal vessels along the new England coast. Pinkies and Chebacco boats had handsome color schemes using only black and green with white sheer lines and limited use of red and yellow. Other combinations of inexpensive pigments were used to improve the simple looks of sloops and schooners in the packet trade, while small pleasure craft and pilot schooners enhanced their appearance in similar ways. Clipper ship owners, finding their vessels' appearance impressive without adding color, settled for unrelieved black hulls. Naval vessels as well preserved their formidable looks with black, relieved only with a white belt in way of the gunports.

The more elaborate ship carvings can be classified in the following categories:

Billetheads: mounted on the bow, at the end of a simple gammon knee, or on the forward end of an elaborate stem-head, they can be scrolls of less or greater intricacy, or sometimes the heads of animals, eagles being the most common. Examples of a sea serpent's head, a pointing hand, and other animal heads have been found. (See Brig "Cadet" in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s (inv. 13); Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43); and Brig Off the Maine Coast, 1851 (inv. 241))

Figureheads: mounted on bows of larger vessels, often with elaborate stem joinerwork (trailboards and headboards with associated knees and rails). Usually these were full-length figures representing the ship's owner, a famous citizen, a mythological person or animal, or an eagle. (See Portrait of the "National Eagle", 1853 (inv. 35) (eagle); New York Harbor, c.1855 (inv. 46); The "Britannia" Entering Boston Harbor, 1848 (inv. 49) (female figures); The Ships "Winged Arrow" and "Southern Cross" in Boston Harbor, 1853 (inv. 54) (dragon and eagle); "Starlight" in Harbor, c.1855 (inv. 249) (dragon); and Steam demi bark Antelope, 615 tons, c.1855 (inv. 375) (antelope))

Trailboards: carved vines or scrollwork abaft the figurehead which trail aft along the stem head in a graceful descending arc, terminating at the hawse pipes. They are usually gilt and frequently ornamented with carved rosettes and other devices. (See Brig "Cadet" in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s (inv. 13); Portrait of the "National Eagle", 1853 (inv. 35); Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43); New York Harbor, c.1855 (inv. 46); and The Ships "Winged Arrow" and "Southern Cross" in Boston Harbor, 1853 (inv. 54))

Headboards: boards mounted to headrails connecting the figurehead to the ship's mainrail at the catheads. While seldom given any decorative carvings, the vessel's nameboards were often mounted to them. (See Brig "Cadet" in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s (inv. 13); Portrait of the "National Eagle", 1853 (inv. 35); Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43); The Ships "Winged Arrow" and "Southern Cross" in Boston Harbor, 1853 (inv. 54); Clipper Ship "Southern Cross" in Boston Harbor, 1851 (inv. 253); and Mary Ann, 1846 (inv. 309))

Catheads: Carved lion heads mounted on the outboard ends of the cathead knees. This term is so archaic that the knees and carvings are treated as one and the same, as in their use, i.e. "catting the anchor" (securing the anchor ring to the cathead). (See Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43); and An American Frigate Hove-to Off the New England Coast (inv. 535))

Quarterboards: Name boards mounted to the vessel's side near the stern, they usually had ornamental edge moldings and sometimes stars or simple scrollwork at each end of the name. (See Portrait of the "National Eagle", 1853 (inv. 35); Mary Ann, 1846 (inv. 309); and Spitfire Entering Boston Harbor (inv. 536))

Transom arches: arch-form panels fitted to the transom, often over gallery lights (windows) or other carvings. They usually have edge moldings, decorative scrollwork, and sometimes a bust or other carved figure at the center.

Other transom carvings: carved eagles, busts, scrollwork and coats of arms can occupy the space between the transom arch and the sternboard. If galleries are present, carved scrollwork may be fitted between the frames of the gallery lights. (See Boston Harbor, c.1850 (inv. 48); The Topsail Schooner "Kamehameha III" in Boston Harbor, 1846 (inv. 301) (eagle); Baltimore Harbor, 1850 (inv. 400) (eagle); and Rough Sea, Schooners, c.1856 (not published) (eagle and flags))

Sternboard: often the bottom plank of the transom on which the vessel's name is carved or painted, seldom with decoration (stars or scrollwork). There is usually simple protective molding above and below the lettering.

Sideboards, or gangway boards: boards on either side of an entry way at main rail level on a large ship, usually between the main and mizen masts. They are carved and painted or (if of fine hardwood) varnished. Most commonly seen on larger vaval vessels, packet ships, and clipper ships.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Brewington, M. V., Shipcarvers of North America, (Barre, MA: Barre Publishing Co., 1962).

2. The American Neptune, Pictorial Supplement XIX, "The Art of the Shipcarver" (Salem, MA: The Peabody Museum, 1977).

3. Ship Figureheads (Boston: State Street Trust Co., n.d.).

4. Edouard A. Stackpole, Figureheads & Carvings at Mystic Seaport (Mystic, CT: The Marine Historical Association, Inc., 1964).

Carved wood with paint and gilt

12 x 22 x 8 in.

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of George W. Woodbury, 1936 (747)

This sea serpent billet head came from the schooner "Diadem" which was built in Essex, Massachusetts, in 1855 and owned by D. Elwell Woodbury and John H. Welsh of Gloucester.

Sea serpents were reportedly sighted here on Cape Ann from colonial times through the mid-nineteenth century. In 1817, more than 50 people, many of them prominent members of the community, reported seeing a serpent in the waters of Gloucester Harbor just off Pavilion Beach. So credible were the reports that the Linnaean Society of New England collected depositions from witnesses and published their findings in a small pamphlet entitled Report of a Committee of the Linnaean Society of New England relative to a Large Marine Animal Supposed to be A Serpent, seen Near Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in August 1817.

Also filed under: Objects » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach »

_sm.jpg)

Commentary

The clipper ship “National Eagle” was built at Medford, Massachusetts, by Joshua T. Foster in 1852 for Fisher & Co. of Boston. Sailed in her first year in the “triangle run” between Boston, New Orleans, and Liverpool, she then made a passage of 134 days from Boston to San Francisco, returning to Boston via Calcutta. The result of this voyage led her owners to put her in the ice trade, taking ice to Calcutta and returning with mixed cargos. In 1863, her voyages between Boston and San Francisco were resumed with numerous extended voyages to other Pacific ports.

In 1865, “National Eagle” was sold to Bates, Holbrook & Candage of Boston, making voyages to numerous ports around the world, though not to any consistent trading route. Sold subsequently to two other shipping firms and registered in New York, she lasted until 1884, when she was wrecked in the Adriatic Sea while bound from New York to Fiume, Austria. Her life span, thirty-one years, was matched or exceeded by very few other clipper ships.

Lane’s painting depicts “National Eagle” outbound from Boston, hove-to with her main sails aback, waiting for the pilot schooner’s yawl boat to row over and pick up the pilot who guided her out of Boston Harbor. She will then proceed on her voyage. This broadside view comes as close as any other Lane vessel portrait in conforming to ship-portrait standards for shipping firms. Lane clearly was not interested in making formalized vessel portraits of ships posed broadside, with all sail set, close-hauled, and drawing perfectly. He constantly varied the settings, weather conditions, and likely situations that were realistic—sometimes threatening, but always depicting competent ship handling.

Lane also had an astute eye for weather and sea conditions. In this case, the fine weather in the foreground is threatened by an approaching front with cirrocumulus and altocumulus clouds leading a darkening bank of cumulonimbus clouds. “National Eagle” will probably have a summer warm front to weather on her maiden voyage to New Orleans.

– Erik Ronnberg

[+] See More