An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

inv. 452

American Vessels No. 1

c. 1845 Colored lithograph on paper 13 x 17 1/2 in. (33 x 44.4 cm) Signed: Lower Left: F.H. Lane, del.

Lower Center: American Vessels, No. 1 / Ship of the Line and First Class Frigate Lower Right: Lane & Scotts, Lith. Collections:

|

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

This store was at 68 Front Street in Gloucester in the early 1840s. In advertisements in the "Cape Ann Light and Telegraph" it is rarely referred to by name, but only by address. It was owned by one of the Davis family and sold everything from gunpowder and tobacco, to "Isle of Shoals Dun Fish" and scaled herring, to almanacs. In 1843 one of the advertisements listed engravings for sale, and this appears to be the location of the exhibition of Lane's print American Vessels No. 1, c.1845 (inv. 452).

Newspaper

p. 3

"Engravings. A splendid lot of Engravings, at 12 1/2 cents each, just rec'd at 68 Front Street, among which are the following: The May Queen, Augusta, Clara, Victoria, Nancy, The Sleeping Beauty, John Tyler, Landing of the Pilgrims, Flower Vase, Brig Somers, Father Matthew, Mourning Pieces, suitable for framing - also Portraits of the People."

Also filed under: Lithography (Sales & Exhibitions) » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper

vol. 17, no. 43

“A beautiful picture of the U.S. Ship of the Line Ohio drawn and published by F. H. Lane of Boston may be seen at 68 Front St.”

Also filed under: "Ohio" (Ship) » // Lithography (Sales & Exhibitions) » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Following the War of 1812, the United States determined to rebuild its navy – to include classes of warships equal or greater in size and fire power than corresponding ships in foreign navies. The largest of these were “ships of the line” carrying a nominal number of guns (74 or 84), but in actuality 90 to 100 guns or more, making them equal to – or more powerful than – the largest warships in foreign navies. (1)

The best of these warships was the 74-gun ship “Ohio”, designed in 1816-1817 by Eckford Webb. Built at New York Navy Yard, 1817-1820, she carried between 86 and 102 guns firing 32- or 42-pound shot. The numbers and sizes of guns varied according to her commanding officers’ wishes. (2) Based at Boston Navy Yard for most of her career, she was the Navy Yard’s receiving ship for many years before being sold out of service in 1883. (3) The “Ohio” would have been a familiar sight to Lane during his years in Boston and the logical subject for a lithograph (perhaps two) and a painting. There was a painting titled "Ship of the Line Ohio" exhibited by Lane in 1851 at New England Art Union in Boston and also a picture exhibited in a Gloucester storefront in 1843.

–Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, “The History of the American Sailing Navy” (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1949), pp. 313, 314, 316.

2. Ibid., p. 314.

3. W. H. Bunting, “Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914” (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), pp. 436, 437.

Government-owned vessels were mainly concerned with defense of the nation (i.e. the U.S. Navy), the regulation of foreign commerce via enforcement of tariffs and seizure of contraband (i.e. the U.S. Revenue Service), and aids to navigation (i.e. the U.S. Lighthouse Service; coastal life-saving was in the hands of civic organizations).

Naval vessels were classified according to a multitude of duties, which in turn determined hull form and size, propulsion (sail, engine-powered, oars), and numbers and duties of crews.

Revenue service vessels varied from small harbor craft, swift-sailing schooners for coastal and harbor patrols, and large square-rigged (and later engine-powered) ships for off-shore duty. These vessels worked closely with customs houses in seaports with significant foreign commerce.

Oil on canvas

15 3/4 x 23 1/4 in.

Hunter Museum of Art, Chattanooga, Tenn., Museum Purchase (1968.4)

Detail of navel vessel.

Also filed under: "Constitution" (U.S. Frigate) »

Oil on canvas

28 x 42 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Corcoran Collection (Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lansdell K. Christie) (2014.136.82)

Detail of naval vessel.

Hand-colored lithograph

Published by N. Currier, New York

Library of Congress catalog number 93514426

Also filed under: Currier (& Ives) – New York »

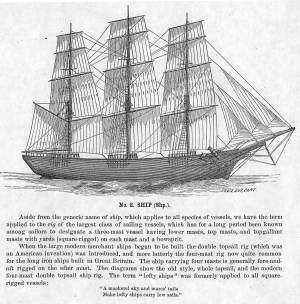

The term "ship," as used by nineteenth-century merchants and seamen, referred to a large three-masted sailing vessel which was square-rigged on all three masts. (1) In that same period, sailing warships of the largest classes were also called ships, or more formally, ships of the line, their size qualifying them to engage the enemy in a line of battle. (2) In the second half of the nineteenth century, as sailing vessels were replaced by engine-powered vessels, the term ship was applied to any large vessel, regardless of propulsion or use. (3)

Ships were often further defined by their specialized uses or modifications, clipper ships and packet ships being the most noted examples. Built for speed, clipper ships were employed in carrying high-value or perishable goods over long distances. (4) Lane painted formal portraits of clipper ships for their owners, as well as generic examples for his port paintings. (5)

Packet ships were designed for carrying capacity which required some sacrifice in speed while still being able to make scheduled passages within a reasonable time frame between regular destinations. In the packet trade with European ports, mail, passengers, and bulk cargos such as cotton, textiles, and farm produce made the eastward passages. Mail, passengers (usually in much larger numbers), and finished wares were the usual cargos for return trips. (6) Lane depicted these vessels in portraits for their owners, and in his port scenes of Boston and New York Harbors.

Ships in specific trades were often identified by their cargos: salt ships which brought salt to Gloucester for curing dried fish; tea clippers in the China Trade; coffee ships in the West Indies and South American trades, and cotton ships bringing cotton to mills in New England or to European ports. Some trades were identified by the special destination of a ship’s regular voyages; hence Gloucester vessels in the trade with Surinam were identified as Surinam ships (or barks, or brigs, depending on their rigs). In Lane’s Gloucester Harbor scenes, there are likely (though not identifiable) examples of Surinam ships, but only the ship "California" in his depiction of the Burnham marine railway in Gloucester (see Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, 1857 (inv. 29)) is so identified. (7)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. R[ichard)] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman’s Friend, 13th ed. (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1873), p. 121 and Plate IV with captions.

2. A Naval Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884), 739, 741.

3. M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World’s Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 536.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 281–87.

5. Ibid.

6. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 26–30.

7. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 67–69.

Photograph

From American Clipper Ships 1833–1858, by Octavius T. Howe and Frederick C. Matthews, vol. 1 (Salem, MA: Marine Research Society, 1926).

Photo caption reads: "'Golden State' 1363 tons, built at New York, in 1852. From a photograph showing her in dock at Quebec in 1884."

Also filed under: "Golden State" (Clipper Ship) »

Oil on canvas

24 x 35 in.

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

Walters' painting depicts the "Nonantum" homeward bound for Boston from Liverpool in 1842. The paddle-steamer is one of the four Clyde-built Britannia-class vessels, of which one is visible crossing in the opposite direction.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Packet Shipping » // Walters, Samuel »

The ensign of the United States refers to the flag of the United States when used as a maritime flag to indentify nationality. As required on entering port, a vessel would fly her own ensign at the stern, but a conventional token of respect to the host country would be to fly the flag of the host country (the United States in Boston Harbor, for example) at the foremast. See The "Britannia" Entering Boston Harbor, 1848 (inv. 49) for an example of a ship doing this. The American ensign often had the stars in the canton arranged in a circle with one large star in the center; an alternative on merchant ensigns was star-shaped constellation. In times of distress a ship would fly the ensign upside down, as can be seen in Wreck of the Roma, 1846 (inv. 250).

The use of flags on vessels is different from the use of flags on land. The importance and history of the flagpole in Fresh Water Cove in Gloucester is still being studied.

The modern meaning of the flag was forged in December 1860, when Major Robert Anderson moved the U.S. garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Adam Goodheart argues this was the opening move of the American Civil War, and the flag was used throughout northern states to symbolize American nationalism and rejection of secessionism.

Before that day, the flag had served mostly as a military ensign or a convenient marking of American territory, flown from forts, embassies, and ships, and displayed on special occasions like American Independence day. But in the weeks after Major Anderson's surprising stand, it became something different. Suddenly the Stars and Stripes flew—as it does today, and especially as it did after the September 11 attacks in 2001—from houses, from storefronts, from churches; above the village greens and college quads. For the first time American flags were mass-produced rather than individually stitched and even so, manufacturers could not keep up with demand. As the long winter of 1861 turned into spring, that old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union cause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for.

– Adam Goodheart, Prologue of 1861: The Civil War Awakening (2011).

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

A view of a Cove on the western side of Gloucester Harbor, with the landing at Brookbank. Houses are seen in the woods back. A boat with two men is in the foreground.

Also filed under: Brookbank » // Fresh Water Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854 CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

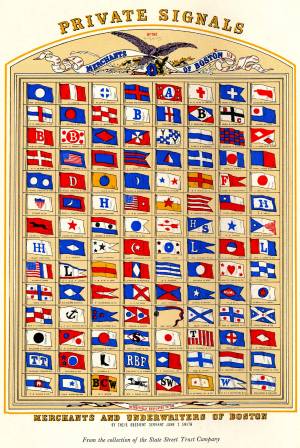

The use of signal flags, for ship-to-ship communication, generally preceded land-based chains of maritime semaphore stations, the latter using flags or rotating arms, until the advent of the electric or magnetic telegraph.

Until the end of the Napoleonic wars, merchant ships generally sailed in convoy as ordered by the escorting warship(s) using a few simple flags. Peace brought independent voyaging, the end of the convoy system, and the realization by various authorities that merchant vessels now needed their own separate means of signaling to each other. This resulted in a handful of rival codes, each with its individual flags and syntax. In general, they each had a section enabling ship identification and also a "vocabulary" section for transmitting selected messages. It was not until 1857 that a common Commercial Code became available for international use, only gradually replacing the earlier ones. All existed side by side for a decade or two.

Signal systems for American ships were originally intended to identify a vessel by name and owner; only later were more advanced systems developed to convey messages. Most basic were private signals, or "house flags", each of a different design or pattern, identifying the vessel's owner; identification charts were local and poorly distributed, limiting their usefulness. A secondary signal, a flag or large pennant bearing the vessel's name, was sometimes flown by larger ships, but pictorial records of them are uncommon. These private signal flags usually flew from the foremasthead or main masthead if a three master ship. Pilot boats had their own identifying flags, blue and white as seen in Spitfire Entering Boston Harbor (inv. 536). Small vessels, such as schooners, often had a "tell-tale" pennant, an often-unmarked and often red flag, that was used to determine wind direction.

A numerical code flag system, identifying vessels by the code numbers, was introduced by Captain Frederick Marryat R.N. in 1817 for English vessels. American vessels soon adopted this system. Elford's "marine telegraphic system" was the first American equivalent to the Marryat code flags, first issued in 1823, and with changes, remaining in use until the late 1850s. Most of the signal flags on vessels depicted by Lane use Elford's; Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43) is a noteworthy example of his depiction of Marryat's. The Elford's Code was popular in America on account of its simplicity and only required six blue and white flags. Eventually these changed to red and white, although it is unclear exactly when this happened. Instructions and a key ot the Elford's Code's use are included in successive editions of the Boston Harbor Signal Book.

Whereas the other codes employ at least ten flags of diverse shapes and colours, there are only six Elford flags in total, representing the numbers one to six. All are uniformly rectangular and monochrome in colour (either blue and white or red and white—or even black and white as in an early photograph). Selected from these six flags each individual vessel is allotted a combination of four flags to be prominently displayed as a vertical hoist. Reading from above down these convey its "designated number." Armed with this number and the type of vessel (e.g. ship, bark, brig, schooner /or steamer) the subject can be uniquely identified by reference to a copy of the Boston Harbor Signal Book for the appropriate year.

– A. Sam Davidson

As reproduced in Yankee Sailing Ship Cards by Allan Forbes and Ralph M. Eastman (Boston: State Street Trust Company, 1948).

Also filed under: "Eastern Star" (Bark) » // Forbes, Robert Bennet »

Harvard Depository: Widener (NAV 578.57)

For digitized version, click here.

Also filed under: Boston Harbor »

Boston: Eastburn's Press

New York Public Library

Complete book is included in Google Books, click here.

In The American Neptune 3, no. 3 (July 1943): 205–21.

Peabody Essex Museum

Descriptions of Marryat, Elford, Rogers, and commercial code signal systems, and private signals. Includes illustrations of flag systems with color keys.

Lane & Scott's Lithography was a Boston-based firm formed by Fitz Henry Lane and John W. A. Scott. The partnership spanned 1844–48, after both artists had apprenticed for prominent Boston lithographer, William Pendleton. The firm was located at 16 Tremont Temple, Boston and created sheet music covers, book illustrations, advertisements, prints, and town views. Lane left the firm around 1847 or 1848 and Scott printed some works under his own name.

This information has been summarized from Boston Lithography 1825–1880 by Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterback.

9 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

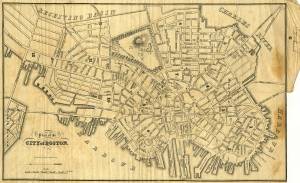

Showing Lane's neighborhood while working in Boston. Lane had studios at the intersection of Washington and State Streets, Summer, Tremont and School Streets.

Also filed under: Boston City Views » // Maps » // Professional » // Residences » // Tremont Temple »

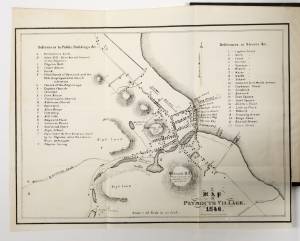

Boston: : Printed for the author, by C.C.P. Moody, Old Dickinson Office–52 Washington Street., 1851

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester.

Call Number LML Plym Russ P851

American Antiquarian Society copy of book inscribed: Belonging to J.G. Orton. Bought in Pilgrim Hall Plymouth, Mass. Oct. 10th 1851

Map of Plymouth Village in 1846 signed: Lane & Scott's Lith., Boston

Boston

Eastburn's Press

Link to Google Books.

Also filed under: "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) » // Forbes, Robert Bennet » // Professional »

_sm.jpg)

Commentary

As indicated below the image, this print was drawn by Lane, and also printed by him at Lane & Scott's.

While in the public’s eyes, the United States Navy’s ships of the line closely resembled each other, there is reason to believe that Lane intended the “Ohio” to be the example in this lithograph. An article in the “Telegraph”, May 31, 1843, mentions a lithograph “drawn and published by F. H. Lane” as depicting that vessel. (1) That lithograph would have been a precursor to American Vessels No. 1, c.1845 (inv. 452), which was published jointly by Lane and John W. A. Scott, who did not form a partnership until a year later. (2) The “Ohio” must have been a subject of interest for Lane, as he also portrayed the vessel in oil on canvas, which was exhibited at the New England Art Union in 1851. (3)

Lane’s depiction of what appears to be a large frigate in the right background cannot be identified as any specific warship. The decorative carvings and gun port arrangement in the stern are at odds with surviving plans and descriptions of American frigates of the period – particularly “Constitution” whose stern configuration is well documented. “Old Ironsides” would seem a likely candidate, having been built in Boston; however, a long absence ending late in 1846, followed by a rebuilding lasting two years, would have limited her value as a “posing subject.” (4)

That this print’s title bore a number indicates that a series of prints was planned, depicting the types of vessels in America’s navy – and perhaps even her merchant marine, given the generic title. Was the scope of this series a factor in Lane & Scott’s parting of the ways? Or was it a casualty?

–Erik Ronnberg

References

1. See supplement “1843 Telegraph”

2. See supplement “Lithography: Lane & Scott’s”

3. See supplement “Boston: New England Art Union”

4. Ira N. Hollis, “The Frigate Constitution” (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900), pp. 230 – 233.

[+] See More