An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

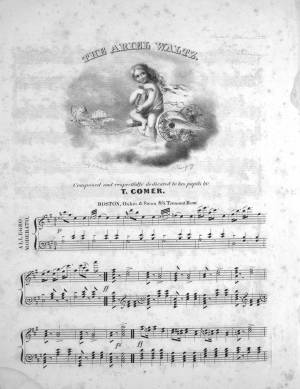

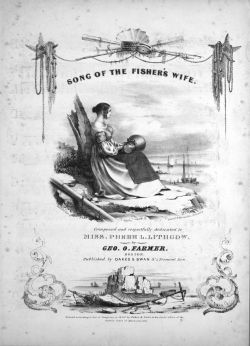

inv. 466

Song of the Fisher's Wife

1840 Lithograph on paper 10 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. (27.6 x 20 cm) F.H. Lane del.

Sharp & Michelin, Printer's Published by Oakes & Swan, 8 1/2 Tremont Row Collections:

On view at the Cape Ann Museum

|

Additional material

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

Stone, oak wood and twine

Sandy Bay Historical Society and Museum, gift of Jack Lawson (1310)

A type of anchor used in dory fishing.

Steel and wood

31 in.

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Erik A. R. Ronnberg, 1995 (2507.20)

A serving mallet is used to cover natural fiber rope with a wrapping of marline (or spun yarn). This covering would reduce chafe and keep water from getting into the cordage and causing rot. The marline would be applied with tar or tar would be added afterwards. This process would take place either in the rigging loft or on the vessel by a professional rigger.

Filed under: Objects » // Vessel details: Rigging and Sails »

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) oncargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Fishing Schooners: While the port of Gloucester is synonymous with fishing and the schooner rig, Lane depicted only a few examples of fishing schooners in a Gloucester setting. Lane’s early years coincided with the preeminence of Gloucester’s foreign trade, which dominated the harbor while fishing was carried on from other Cape Ann communities under far less prosperous conditions than later. Only by the early 1850s was there a re-ascendency of the fishing industry in Gloucester Harbor, documented in a few of Lane’s paintings and lithographs. Depictions of fishing schooners at sea and at work are likewise few. Only A Smart Blow, c.1856 (inv. 9), showing cod fishing on Georges Bank (4), and At the Fishing Grounds, 1851 (inv. 276), showing mackerel jigging on Georges Bank, are known examples. (5)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 74–76.

5. Howard I. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 58–75, 76–101.

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

Stereograph card

Frank Rowell, Publisher

stereo image, "x " on card, "x"

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View showing a sharpshooter fishing schooner, circa 1850. Note the stern davits for a yawl boat, which is being towed astern in this view.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Model made for marine artist Thomas M. Hoyne

scale: 3/8" = 1'

Thomas M. Hoyne Collection, Mystic Seaport, Conn.

While this model was built to represent a typical Marblehead fishing schooner of the early nineteenth century, it has the basic characteristics of other banks fishing schooners of that region and period: a sharper bow below the waterline and a generally more sea-kindly hull form, a high quarter deck, and a yawl-boat on stern davits.

The simple schooner rig could be fitted with a fore topmast and square topsail for making winter trading voyages to the West Indies. The yawl boat was often put ashore and a "moses boat" shipped on the stern davits for bringing barrels of rum and molasses from a beach to the schooner.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seafarers in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 29–31.

Also filed under: Hand-lining » // Ship Models »

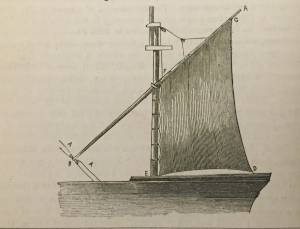

20 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

The image, as originally drafted, showed only spars and sail outlines with dimensions, and an approximate deck line. The hull is a complete overdrawing, in fine pencil lines with varied shading, all agreeing closely with Lane's drawing style and depiction of water. Fishing schooners very similar to this one can be seen in his painting /entry:240/.

– Erik Ronnberg

Newspaper

"Shipping Intelligence: Port of Gloucester"

"Fishermen . . . The T. [Tasso] was considerably injured by coming in contact with brig Deposite, at Salem . . ."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newsprint

From bound volume owned by publisher Francis Procter

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"A Prize Race—We have heard it intimated that some of our fishermen intend trying the merits of their "crack" schooners this fall, after the fishing season is done. Why not! . . .Such a fleet under full press of sail, would be worth going many a mile to witness; then for the witchery of Lane's matchless pencil to fix the scene upon canvass. . ."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Also filed under: Cape Ann Advertiser Masthead »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Rocky Neck » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

See p. 254.

As Erik Ronnberg has noted, Lane's engraving follows closely the French publication, Jal's "Glossaire Nautique" of 1848.

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester »

Wood, cordage, acrylic paste, metal

~40 in. x 30 in.

Erik Ronnberg

Model shows mast of fishing vessel being unstepped.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Fishing »

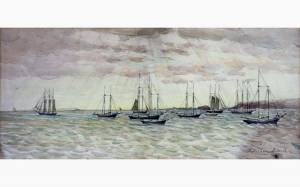

Watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 19 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Rev. and Mrs. A. A. Madsen, 1950

Accession # 1468

Fishing schooners in Gloucester's outer harbor, probably riding out bad weather.

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Print from bound volume of Gloucester scenes sent to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

11 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

Schooner "Grace L. Fears" at David A. Story Yard in Vincent's Cove.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Shipbuilding / Repair » // Vincent's Cove »

Fishing in Lane's time saw the height of hand-lining gear use and the introduction of multi-hook fishing (trawling) for ground fish (cod, halibut, haddock, hake, etc.). Then new to the mackerel fishery was the purse seine, which allowed a whole school of mackerel to be caught in one "set" instead of hand-lining over the rails, one fish at a time. These changes in fishing technology, in time, brought new life to the fishing industry on Cape Ann, which had ceded her leadership in the New England fishing industry to Maine. (1)

Lane would not live to see Cape Ann's restored dominance in the fisheries, nor did his late work document the process of change in any significant way. Apparently content with what he saw and depicted in the 1840s and early '50s, he did little to explore later developments and focused more on other types of merchant vessels in other harbors.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

Wayne O'Leary, Maine Sea Fisheries (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), 160–79.

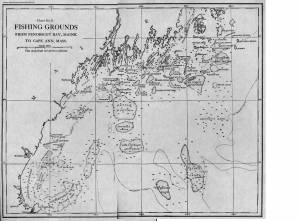

Chart

Fishery Industries of the United States, Sect. 3

Also filed under: Penobscot Bay »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Newsprint

From bound volume owned by publisher Francis Procter

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"A Prize Race—We have heard it intimated that some of our fishermen intend trying the merits of their "crack" schooners this fall, after the fishing season is done. Why not! . . .Such a fleet under full press of sail, would be worth going many a mile to witness; then for the witchery of Lane's matchless pencil to fix the scene upon canvass. . ."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Schooner (Fishing) »

Newspaper

This article details a War Correspondence and an argument against the retrenchment of the Gloucester fishing business.

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper

"They remarked, that if the fishing business is to be continued in the town of Gloucester, and followed successfully, there must be a retrenchment in the outfits..."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newsprint

Cape Ann Advertiser

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"VISIT TO LANE'S STUDIO.

We called at the studio of this artist a few days ago, and found several new paintings had been added to his collection since our last visit. The first that arrested our attention was a view of Good Harbor Beach. . . .

A scene outside Eastern Point, during a fresh sou'wester, is full of life, and faithfully portrayed on the canvass. . . .

A fancy sketch, representing a storm scene, is also on exhibition. . . .

The Artist has now on his easel a large picture 36x60, just commenced, which we should judge would be his master-piece. It will be on exhibition when finished, and we forbear a description of it at this time. Mr. Lane, as a marine painter, ranks first in the country, and we are pleased to chronicle his success in producing such life-like pictures."

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Diorama of Gloucester fishing boats, which includes several models now in the collection of the Cape Ann Museum

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Ship Models »

Wood, wicker, cordage

19 1/2 x 23 in.

Cape Ann Museum (2089-3 G/O EARR)

Used at wharfside for carrying fish and small fishing gear.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (4) »

Also filed under: Mackerel Fishing » // Objects »

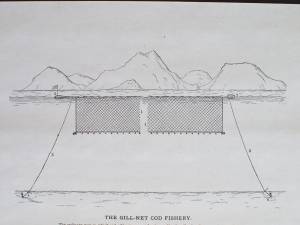

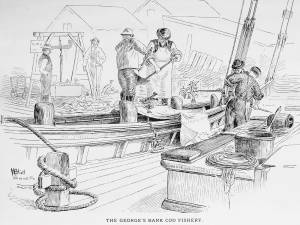

In G. Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

Also filed under: Gill Netting »

1873 Gloucester City Directory (1)

"The design is very pretty and appropriate . . .In the centre of the seal is a representation of a fishing schooner anchored on the banks, copied from a picture painted by that talented artist, the late Mr. Fitz H. Lane." (2)

References:

1. Gloucester City Directory. (Gloucester, MA: Sampson, Davenport, & Co., 1873), front page.

2. "The Town Seal": designed by Capt. Addison Center," Cape Ann Weekly Advertiser, February 9, 1872.

Also filed under: Center, Addison » // Gloucester, Mass. Town Seal » // Publications »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Stone, oak wood and twine

Sandy Bay Historical Society and Museum, gift of Jack Lawson (1310)

A type of anchor used in dory fishing.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Objects »

In G. Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)

A vessel having returned from the fishing grounds with a fare of split salted cod, is discharging it at a fish pier for re-salting and drying. The fish are tossed from deck to wharf with sharp two-pronged gaffs, and from there to a large scale for weighing. From there, they will be taken to another part of the wharf for washing and re-salting.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Drying Fish » // Georges Bank, Mass. »

Wood, cordage, acrylic paste, metal

~40 in. x 30 in.

Erik Ronnberg

Model shows mast of fishing vessel being unstepped.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Schooner (Fishing) »

In G. Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)

See pl. 45.

Underrunning cod gill-nets in Ipswich Bay, Mass.

Also filed under: Gill Netting »

Also filed under: Drying Fish »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View shows Main Street Fish Market, Gloucester, Mass.

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

Oakes & Swan were sheet music engravers and publishers, with a shop located on Tremont Row in Boston, Massachusetts. This was only a brief partnership (c.1840) of William H. Oakes and Samuel Swan. Oakes, however, went on to publish sheet music under his own name from 1840 to 1851.

– Catharina Slautterback

Newspaper

Boston Weekly Magazine Devoted to Moral and Entertaining Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts

"Deception"

v.iii, n.22

p. 175

"Now Boston people do surpass other cities in the execution of almost every species of artizanship [sic] connected with the press; and to none should a higher palm be awarded than to Wm. H. OAKES, music engraver and publisher, Tremont Row, for the beautiful style of his issues. His vignette titles are far superior to anything across the water, and are better specimens of art than half the engravings for sale at the print shops. Who has not seen and admired his "Old Arm Chair," with the music by Russell? and it is of this we would speak; for we have been shown another Old Arm Chair . . . which is an exact copy of Mr. Oakes's . . ."

Also filed under: Boston – Oakes Music Store » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Sharp & Michelin was the lithography firm of William Sharp (1803–75) and Francis Michelin at 17 Tremont Row, Boston. Both Michelin and Sharp had worked at the London-based lithography firm of Charles Hullmandel before emigrating to America around 1839. Sharp & Michelin was founded the following year, but was shortlived, lasting from 1840–41. The work produced by Sharp & Michelin is regarded as interesting and highly accomplished, a result of William Sharp's determination to establish himself in Boston.

This information has been summarized from Boston Lithography 1825–1880 by Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterback.

Also filed under: Champney, Benjamin »

One of the first uses of lithography, after its invention in France in the late eighteenth century and its development in America, was for sheet music covers. The music itself was printed from engraved copper plates, which was necessary for the clarity and evenness demanded by the public for the music. However, lithography provided a quick and inexpensive way to provide enticing pictorial title pages, or covers, for sheet music. Pendleton's shop produced the first lithographic sheet music cover printed in the United States in 1826. Much of Lane's work at Pendleton's involved sheet music covers, and examples here by other artists show some of the conventions around the designs.

This information has been summarized from Boston Lithography 1825–1880 by Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterback.

Parker & Ditson

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.

Dedicated to the Tiger Boat Club.

Also filed under: Bufford, J. H. Lith. – Boston » // Parker & Ditson, Pub. – Boston » // Thayer's, Lith. – Boston » // Tiger Boat Club » // Yacht & Small Pleasure Craft »

Comp. Marshall S. Pike, Esq.

Also filed under: Bufford, J. H. Lith. – Boston »

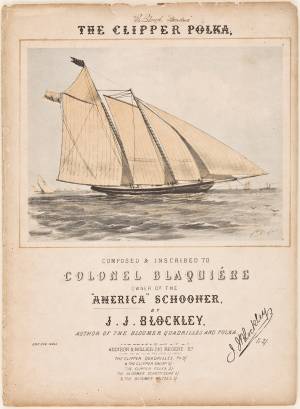

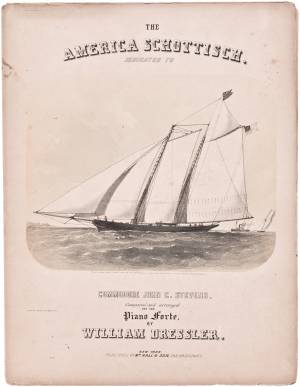

Paper, ink

13 x 10 in (33.02 x 25.4 cm)

Peabody Essex Museum (M26784)

"composed and inscribed to Colonel Baquiere, Owner of the "America" Schooner, 1851-1856"

Also filed under: "America" (Schooner Yacht) »

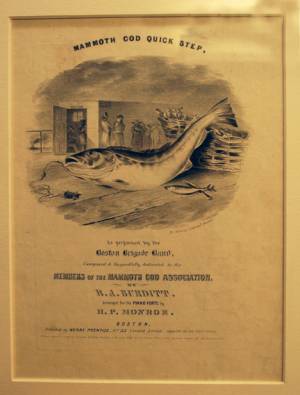

T. Moore's Lithography, Boston

12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.

20 x 16 3/4 in (Framed)

Cape Ann Museum, Museum Purchase (2014.089.2)

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Johnston, David Claypoole » // Moore's, T. - Lith. - Boston »

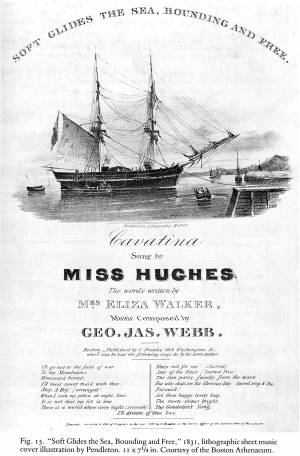

Lithographic sheet music

11 x 7 1/4 in.

Boston Athenaeum

Also filed under: Pendleton's, Lith. – Boston » // Salmon, Robert »

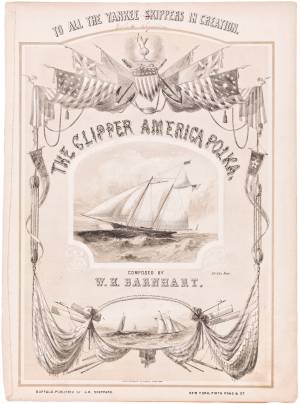

Ink, paper

13 x 10 in (33.02 x 25.4 cm)

Peabody Essex Museum

Also filed under: "America" (Schooner Yacht) »

Ink on paper

13 x 10 inches

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. (M26750)

Also filed under: "America" (Schooner Yacht) »

Commentary

This sheet music cover was designed and drawn on stone by Lane and printed by Sharp & Michelin. The publisher was Oakes & Swan.

[+] See More