An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

inv. 297

Pilot Pendant: Departing

Oil on canvas 14 x 17 in. (35.6 x 43.2 cm)

Private collection

|

Related Work in the Catalog

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

During the years after the war of 1812 and before the Civil War, the port of Boston was a center of American deep-water shipping. Trading with China, India, and the West Indies, which had fueled maritime growth in the early years of the century gave way to re-exporting these goods and foreign trade based on the shoe and textile trades. Although second to New York in terms of shipping tonnage, many of New York's shipbuilders and merchants were Boston based. In addition, ship building continued in Boston. Also, the coastal trade (the domestic trade up and down the coast) was still the most efficient way to transport goods and passengers, and accounts for much of the tonnage and shipping traffic.

Although dwarfed by New York, Boston was an active port in the 1840s and 1850s. Its registered tonnage rose from 149,186 in 1840 to 270,510 in 1850. The harbor was a crowded place. For example, on September 18, 1850, 32 ships, 49 barks, 47 brigs, and 52 schooners were reported at Boston.(1)

In 1849, foreign entries at Boston included 215 ships, 305 barks, 908 brigs, and 52 schooners. Coastwise arrivals included 193 ships, 488 barks, 1087 brigs, 4287 schooners, 89 sloops, and 65 schooners.(2)

(1) W.H. Bunting, p.8.

(2) Ibid.

For more information:

Samuel Eliot Morrison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860

W.H. Bunting, Portrait of a Port, Boston 1852-1914 Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1971.

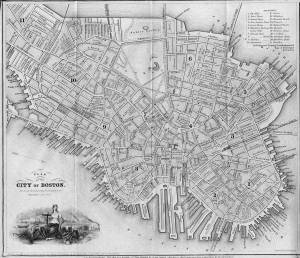

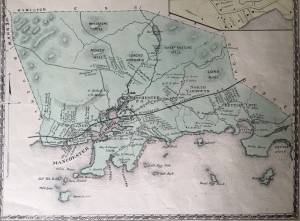

Printed map inside Boston Almanac

Published by B. B. Mussey & Co. and Thomas Groom, Boston

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (R910.45 B65 1848)

Map at front of almanac with Tremont Temple highlighted.

Also filed under: Boston City Views » // Maps » // Tremont Temple »

Harvard Depository: Widener (NAV 578.57)

For digitized version, click here.

Also filed under: Signal Systems (Flags & Maritime Codes) »

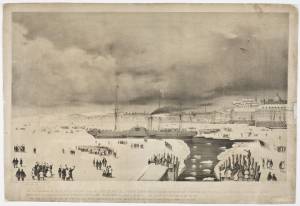

Tinted lithograph with hand coloring

13 7/8 x 22 3/8 in.

Boston Athenaeum

From Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterback, Boston Lithography, 1825–1880: The Boston Atheneaum Collection (Boston: Athenaeum, 1991): "Tidd drew this print when he was a consulting engineer for Simpson's. He has depicted the clipper ship 'Southern Cross' in the dry dock. Built in 1851, she was known for having sailed from San Francisco to Hong Kong in the record breaking time of thirty-two days. The Bethlehem Ship Building Company eventually took over this location and operated a dry dock there until the mid 1940s."

Also filed under: "Southern Cross" (Clipper Ship) » // M. M. Tidd, Lith. – Boston »

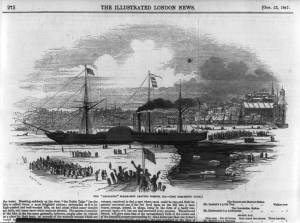

Library of Congress Catalog Number 2004671768

Also filed under: "Britannia" (Cunard Steamship) »

1853

Bostonian Society (1884.0209)

Also filed under: Scott, John W. A. »

1 print : lithograph, tinted ; image 50.3 x 111.9 cm., 68.7 x 121.2 cm.

View of the city of Boston from East Boston showing Boston Harbor. The wharves of East Boston can be seen in the foreground.

Number nine of thirty-eight city views published in "Whitefield's Original Views of (North) American Cities (Scenery).

On stone by Charles W. Burton after a drawing by Edwin Whitefield.

Inscribed in brown ink lower right corner of sheet: "Boston Athenaeum from Josiah Quincy. September 28, 1848."

Local Notes:#1848.1.

In the ninteenth century, the term "bark" was applied to a large sailing vessel having three masts, the first two (fore and main) being square-rigged; the third (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged. The reduced square-rig made the vessel easier and more economical to handle, using a smaller crew. (1)

Barks had significant presence in mid-nineteenth-century America, as indicated by Lane’s depictions of them. Hardly any are to be found in his scenes of major ports, but some do appear in his Cape Ann scenes (see The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), View of Gloucester, 1859 (inv. 91), Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 391), and Bark "Eastern Star" of Boston, 1853 (inv. 571)), also in views of other small ports and of coastal shipping (see Clipper Ship "Southern Cross" in Boston Harbor, 1851 (inv. 253), Merchantmen Off Boston Harbor, 1853 (inv. 267), Approaching Storm, Owl's Head, 1860 (inv. 399), and Bark "Mary" (inv. 629)).

Brigs, and to a lesser extent ships, were the vessels of choice for Gloucester’s foreign trade in the first half of the nineteenth century. They brought cargos from the West Indies, South America, and Europe, anchoring in the deeper parts of the Inner Harbor while lighters off-loaded the goods and landed them at the wharves in Harbor Cove, by then too shallow for the newer, larger merchant vessels coming into use. (2) By mid-century, barks were gradually replacing brigs and ships, while the trade with Surinam was removed to Boston in 1860. (3)

Some bulk cargos still had to be landed in Gloucester, salt for curing fish being the most important. “Salt barks” brought Tortugas salt from the West Indies, and in the 1870s, Italian salt barks began bringing Trapani salt from Sicily. The importation of salt by sailing ships ended with the outbreak of World War I. (4)

The term barkentine, like the bark, pre-dates the nineteenth century, but in the mid- to late 1800s referred to a large vessel of three masts (or more), with only the fore mast square-rigged, the others being fore-and-aft-rigged. In Lane’s time, the term was little known in the United States, while many other names were coined for the rig. One of these early terms was demi-bark, probably from the French demi-barque, which was applied to a very different kind of vessel. (5) Lane’s depictions of these rigs include a lithograph of the steam demi-bark "Antelope" View of Newburyport, (From Salisbury), 1845 (inv. 499) and at least three depictions of Cunard steamships The "Britannia" Entering Boston Harbor, 1848 (inv. 49), Cunard Steamship Entering Boston Harbor (inv. 197), and Cunard Liner "Britannia", 1842 (inv. 259). (6) None of these subjects typify the barkentine rig as applied to sails-only rigs as they developed in the years after Lane’s death.

– Erik Ronnberg (May, 2015)

References:

1. R[ichard] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman's Friend (Boston; Thomas Groom & Co., 1841. 13th ed., 1873), 97 and Plate IV with captions; and M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 43.

2. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 56, note 10; 67, note 7.

3. James R. Pringle, History of the Town and City of Gloucester (1892. Reprint: Gloucester, MA, 1997), 106–08.

4. Raymond McFarland, A History of the New England Fisheries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1911), 95–96; and Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History (New York: Walker & Co., 2002), 419–420.

5. Parry, 44, 167. Dana has neither definition nor illustration of this rig.

6. J[ohn] W. Griffiths, “The Japan and China Propeller Antelope," U.S. Nautical Magazine III (October 1855): 11–17. This article includes an impression of Lane’s lithograph on folded tissue.

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This view of Gloucester's Inner Harbor shows three square-rigged vessels in the salt trade at anchor. The one at left is a (full-rigged) ship; the other two are barks. By the nature of their cargos, they were known as "salt ships" and "salt barks" respectively. Due to their draft (too deep to unload at wharfside) they were partially unloaded at anchor by "lighters" before being brought to the wharves for final unloading.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Salt » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

When inbound merchant ships approached their destination ports, they were required by law to pick up a pilot to guide the vessel safely into the harbor. Pilot schooners were stationed outside the ports to transfer one of their pilots to the incoming ship by means of a small rowing boat designed for this task, even in heavy seas. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, this boat was called a canoe. In other ports, such as New York, they were of different design and called yawls. (1)

In hull form, the pilot canoe bore no resemblance to any Native American watercraft by that name. The term’s origin seems to be French, where a canot was a small, beamy, and very seaworthy rowing boat. A bilingual guide to French nautical terms and their English equivalents contains a sample dialogue between a shipmaster and a pilot wherein the term canot is used for the pilot’s boat. (2) Definitions and descriptions of the French canot as a ship's boat used for communication between vessels and between ship and shore support the French origin for the Boston pilots' term "canoe." (3) Pilot yawls, as built and used in New York, closely resembled Whitehall boats in design, though with variations in construction. (4)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Charles I. Lampee, “Memories of Cruises on Boston Pilot Boats of Long Ago,” Nautical Research Journal 10, no. 2: 44–58.

2. Eugène Pornain, Termes Nautiques (Sea Terms) Anglais Francais, 13th ed. (Paris: Augustin Challamel,1890), 181–83.

3. John Harland, Seamanship in the Age of Sail (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1984), 283–84; and Lecomte, Jules, Dictionnaire Pittoresque de Marine (Paris: 1835; Douarnenez: Editions de L'estran, 1982), see "canot."

4. Erik A.R. Ronnberg, Jr., “Boston Pilot Canoes Revisited,” Nautical Research Journal 39, no. 3: 166.

Oil on canvas

23 1/2 x 36 in. (59.7 x 91.4 cm)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of the Estate of Marjory A. Johnson, 1988 (2612.00)

In this detail, the canoe can just be discerned conveying the pilot from the pilot boat to the clipper ship.

Pilot schooners in the pre-Civil War period were small- to medium-size schooners (60 to 90 feet on deck) which transported pilots to inbound vessels and picked up pilots from outbound vessels. Their presence was indicated by a signal flag hoisted on the main mast. In Boston, the pilot flag was blue and white, divided vertically. In New York, the flag was solid blue, sometimes with stars in rows. Other ports had pilot flags of differing designs.

When a merchant ship approached its destination port, it was (and still is) mandated by law to take on a pilot to guide the ship through unfamiliar channels, tidal currents, and other hazards to reach safe anchorage or berthing. The same law applies to outbound ships, which must take on a pilot to guide the vessel safely, leaving the pilot with a stationed pilot schooner once the port is cleared. The small rowing boat used to transfer the pilot from schooner to ship (or ship to schooner) was called a pilot yawl (in New York) or a pilot canoe (in Boston).

In many American ports, piloting could be a very competitive business, with rival schooners racing to an inbound ship to be first to put a pilot on board. These vessels were sometimes sold out of service to become yachts, while yachts were occasionally sold into pilot service, so adapted for speed were both types.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

Tom Cunliff, Pilots 1: Pilot Schooners of North America and Great Britain (Douarnenez, France: Le Chasse-Maree/Maritime Life and Traditions; and Brooklin, ME: Wooden Boat, 2001).

Photograph

Johnson, H. and Lightfoot, F.S.: Maritime New York in Nineteenth-Century Photographs, Dover Publications, Inc., New York

The New York pilot boats would sail out to meet large incoming ships, flying the blue and white flag. The pilot would board the large ship and guide her into harbor. On outgoing trips the pilot boat would pick up the pilot after the ship in his charge had cleared the harbor.

Also filed under: New York Harbor »

Mahogany, cotton, paper, metal

29 x 34 x 6 1/2 in (73.66 x 86.36 x 16.51 cm)

M27746

Peabody Essex Museum

Also filed under: Ship Models »

The ensign of the United States refers to the flag of the United States when used as a maritime flag to indentify nationality. As required on entering port, a vessel would fly her own ensign at the stern, but a conventional token of respect to the host country would be to fly the flag of the host country (the United States in Boston Harbor, for example) at the foremast. See The "Britannia" Entering Boston Harbor, 1848 (inv. 49) for an example of a ship doing this. The American ensign often had the stars in the canton arranged in a circle with one large star in the center; an alternative on merchant ensigns was star-shaped constellation. In times of distress a ship would fly the ensign upside down, as can be seen in Wreck of the Roma, 1846 (inv. 250).

The use of flags on vessels is different from the use of flags on land. The importance and history of the flagpole in Fresh Water Cove in Gloucester is still being studied.

The modern meaning of the flag was forged in December 1860, when Major Robert Anderson moved the U.S. garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Adam Goodheart argues this was the opening move of the American Civil War, and the flag was used throughout northern states to symbolize American nationalism and rejection of secessionism.

Before that day, the flag had served mostly as a military ensign or a convenient marking of American territory, flown from forts, embassies, and ships, and displayed on special occasions like American Independence day. But in the weeks after Major Anderson's surprising stand, it became something different. Suddenly the Stars and Stripes flew—as it does today, and especially as it did after the September 11 attacks in 2001—from houses, from storefronts, from churches; above the village greens and college quads. For the first time American flags were mass-produced rather than individually stitched and even so, manufacturers could not keep up with demand. As the long winter of 1861 turned into spring, that old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union cause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for.

– Adam Goodheart, Prologue of 1861: The Civil War Awakening (2011).

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

A view of a Cove on the western side of Gloucester Harbor, with the landing at Brookbank. Houses are seen in the woods back. A boat with two men is in the foreground.

Also filed under: Brookbank » // Fresh Water Cove » // Historic Photographs »

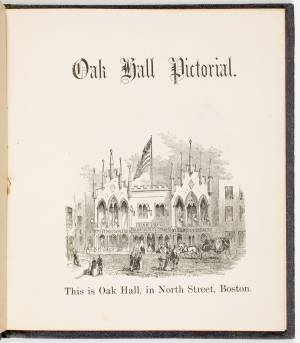

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854 CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass. (CL.F9116.011.1854)

Also filed under: Oak Hall »

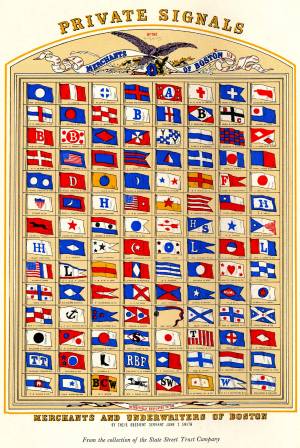

The use of signal flags, for ship-to-ship communication, generally preceded land-based chains of maritime semaphore stations, the latter using flags or rotating arms, until the advent of the electric or magnetic telegraph.

Until the end of the Napoleonic wars, merchant ships generally sailed in convoy as ordered by the escorting warship(s) using a few simple flags. Peace brought independent voyaging, the end of the convoy system, and the realization by various authorities that merchant vessels now needed their own separate means of signaling to each other. This resulted in a handful of rival codes, each with its individual flags and syntax. In general, they each had a section enabling ship identification and also a "vocabulary" section for transmitting selected messages. It was not until 1857 that a common Commercial Code became available for international use, only gradually replacing the earlier ones. All existed side by side for a decade or two.

Signal systems for American ships were originally intended to identify a vessel by name and owner; only later were more advanced systems developed to convey messages. Most basic were private signals, or "house flags", each of a different design or pattern, identifying the vessel's owner; identification charts were local and poorly distributed, limiting their usefulness. A secondary signal, a flag or large pennant bearing the vessel's name, was sometimes flown by larger ships, but pictorial records of them are uncommon. These private signal flags usually flew from the foremasthead or main masthead if a three master ship. Pilot boats had their own identifying flags, blue and white as seen in Spitfire Entering Boston Harbor (inv. 536). Small vessels, such as schooners, often had a "tell-tale" pennant, an often-unmarked and often red flag, that was used to determine wind direction.

A numerical code flag system, identifying vessels by the code numbers, was introduced by Captain Frederick Marryat R.N. in 1817 for English vessels. American vessels soon adopted this system. Elford's "marine telegraphic system" was the first American equivalent to the Marryat code flags, first issued in 1823, and with changes, remaining in use until the late 1850s. Most of the signal flags on vessels depicted by Lane use Elford's; Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43) is a noteworthy example of his depiction of Marryat's. The Elford's Code was popular in America on account of its simplicity and only required six blue and white flags. Eventually these changed to red and white, although it is unclear exactly when this happened. Instructions and a key ot the Elford's Code's use are included in successive editions of the Boston Harbor Signal Book.

Whereas the other codes employ at least ten flags of diverse shapes and colours, there are only six Elford flags in total, representing the numbers one to six. All are uniformly rectangular and monochrome in colour (either blue and white or red and white—or even black and white as in an early photograph). Selected from these six flags each individual vessel is allotted a combination of four flags to be prominently displayed as a vertical hoist. Reading from above down these convey its "designated number." Armed with this number and the type of vessel (e.g. ship, bark, brig, schooner /or steamer) the subject can be uniquely identified by reference to a copy of the Boston Harbor Signal Book for the appropriate year.

– A. Sam Davidson

As reproduced in Yankee Sailing Ship Cards by Allan Forbes and Ralph M. Eastman (Boston: State Street Trust Company, 1948).

Also filed under: "Eastern Star" (Bark) » // Forbes, Robert Bennet »

Harvard Depository: Widener (NAV 578.57)

For digitized version, click here.

Also filed under: Boston Harbor »

Boston: Eastburn's Press

New York Public Library

Complete book is included in Google Books, click here.

In The American Neptune 3, no. 3 (July 1943): 205–21.

Peabody Essex Museum

Descriptions of Marryat, Elford, Rogers, and commercial code signal systems, and private signals. Includes illustrations of flag systems with color keys.

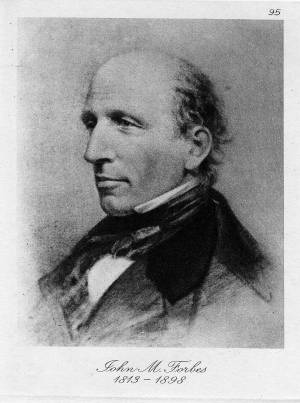

John Murray Forbes was the brother of Robert Bennet Forbes, a ship's captain who commissioned a number of works from Lane. John Murray Forbes purchased land with his brother in Milton, Massachusetts and built a house for their mother there, known as the Robert Bennet Forbes house. According to the 1848 Boston Directory, John Murray Forbes had an office at 48 State Street.

Book "Family Photographs" 1:45

Privately Printed: The Riverside Press

Collection of the Forbes House Museum.

Also filed under: Forbes, Robert Bennet » // Manchester, Mass. »

Also filed under: Forbes, Robert Bennet »

Robert Bennet Forbes (1804–89) of Boston was a key figure in his family's business in the China trade. While his brothers and cousins took positions as land-based merchants stationed either in Boston or Canton, Robert Bennet Forbes chose life at sea. He went on many trips to China, starting in 1817 as a cabin boy—thirteen years old—and eventually as a ship captain.

Forbes became a partner in the firm in 1832, known by then as Russell & Co., Canton, and went for a two-year trip to China in 1838–40 as a merchant. He was a proponent of steam power, which helped ships on the long voyage to China and Japan, and gave them the speed to evade the pirates who were ever present in the opium trade. His firm built about 70 ships, of which he was owner or part owner of several.

Robert Bennet Forbes also helped to introduce yachting as a sport, and participated in some of the first yacht races. His book Personal Reminiscences, published in 1892, lists many of these exploits, as well as all of the vessels he owned and built.

Forbes was known for his adventurous spirit. In 1846, when news of the Irish famine reached Boston, he convinced the U.S.Navy to lend him the "USS Jamestown" to take food to famine sufferers in 1847. He was the first civilian given the honor of commanding a naval vessel, and he crossed the Atlantic in a record seventeen days. Forbes wrote a book about his trans-Atlantic voyage for which he commissioned Lane to make the frontispiece illustration.

The "Jamestown" commission was one of several works Lane made for Forbes. Forbes was not only adventurous but innovative, and he commissioned Lane to make works after two of his newly designed steam vessels: the "Massachusetts," a packet ship that used steam power to supplement wind power, and the "Antelope," that relied primarily on steam power.

The Forbes family lived in Milton, Massachusetts, and also had a home in Beverly, Massachusetts. In 1856 Forbes bought land in West Manchester and built a summer home there which he christened "Masconomo" after the sagamore, chief of the Agawam.

In 1834 Captain Forbes married Rose Greene Smith. She died September 18, 1885, having borne her husband three children: Robert Bennet Forbes (1837–June 30, 1891); Edith Forbes, who married Charles Eliot Perkins; and James Murray Forbes (b. July 17, 1845). He died on November 23, 1889 in Milton.

As reproduced in Yankee Sailing Ship Cards by Allan Forbes and Ralph M. Eastman (Boston: State Street Trust Company, 1948).

Also filed under: "Eastern Star" (Bark) » // Signal Systems (Flags & Maritime Codes) »

Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum

1011.2 F695

Also filed under: "Massachusetts" (Auxiliary Steam Packet Ship) »

vol. 1, no. 1

January 1941

pp. 51-57

Also filed under: "Antelope" (Steam Demi-Bark) » // "Massachusetts" (Auxiliary Steam Packet Ship) »

Typed transcription of photograph caption

Manchester Historical Museum, Manchester, Mass.

Also filed under: Manchester, Mass. »

map

Manchester Historical Museum

Also filed under: Manchester, Mass. »

c. 1857

Manchester Historical Museum

In 1856 Robert Bennet Forbes bought nineteen acres of land for $2,800 from Israel F. Tappan in the section of the West Manchester shore known in those days as Newport. There he built Masconomo, named for the sagamore of the Agawam. In her unpublished letters to her son Robert, his wife Rose Greene Forbes wrote:

"...I think Father will put up a good sized cheap summer house, rough pillars, pine furniture etc., and very likely we shall all be there for two months next summer. He means to show people how rational people ought to live at the seaside. What nice times we shall have..."

The house was sold to Benjamin G. Boardman in 1865.

Also filed under: Manchester, Mass. »

Book "Family Photographs" 1:45

Privately Printed: The Riverside Press

Collection of the Forbes House Museum.

Also filed under: Forbes, John Murray » // Manchester, Mass. »

Book

University Press, John Wilson and Sons, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Second edition, 1882, contains "Rambling Recollections Connected with China." Google book version.

Also filed under: "Massachusetts" (Auxiliary Steam Packet Ship) »

Also filed under: Forbes, John Murray »

Robert Bennet Forbes scrapbook

vol. 1, p. 4

Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum (SCR 4)

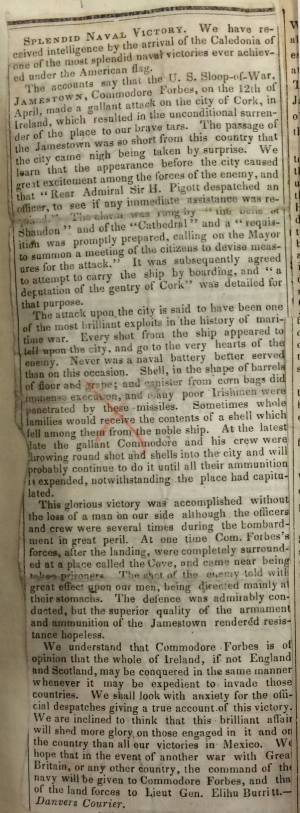

"SPLENDID NAVAL VICTORY. We have received intelligence by the arrival of the Caledonia of one of the most splendid naval victories ever achieved under the American flag..." This article is a humorous metaphor, comparing Forbes' mission to bring food to the starving Irish to a naval assault on the city of Cork.

Also filed under: "Caledonia" (Cunard Steamship) » // "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Perhaps painted in Canton

Collection of the Forbes House Museum

Given to the Forbes House Museum by H.A. Crosby Forbes, Ph.D., Robert P. Forbes, Ph.D., and Douglas B. Forbes in 2012

The painting was commissioned by Robert Bennet Forbes to commemorate the death of his brother, Thomas Tunno Forbes, in 1829 on "The Haide" during a storm off the coast of Macao.

Collection of the Forbes House Museum, Milton, Mass.

Scene depicts the "Jamestown" being towed out of Charlestown Navy Yard. Plaque reads: "To Captain R. Bennett [sic] Forbes / From his English friends. / The "Jamestown" American Sloop of War as she left Boston under his command / bound to CORK with DONATIONS of FOOD / freight free for the Irish. / 1847."

Also filed under: "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) »

Boston

Eastburn's Press

Link to Google Books.

Also filed under: "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) » // Lane & Scott's, Lith. – Boston » // Professional »

16 1/2 x 20 1/2 in., on sheet 18 1/8 x 22 1/2 in.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.

One of these lithographs was given to R. B. Forbes at an event held on the 19th of April at the Cork Temperance Institute.

"U.S. Sloop of war, Jamestown: Capt. R. B. Forbes. This print, commemorative of the splendid generosity of the American government in dismantling a ship of war for a mission of peace and charity, & of the noble-hearted citizens who humanely & benevolently responded to the call of Irish distress, is respectfully dedicated to the President, House of Representatives, Congress and people of the United States of America, by their obedt. servants, George M. W. Atkinson, William Scraggs, Cove of Cork 13th April, 1847"

Also filed under: "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) »

Collection of the Forbes House Museum, Milton, Massachusetts

Gift to R. B. Forbes from the U.S. Navy to commemorate voyage of the "Jamestown."

Also filed under: "Jamestown" (U.S. Sloop of War) »

Commentary

Pilot Pendant: Approaching (inv. 296) and Pilot Pendant: Departing (inv. 297) were in all likelihood created as a pair, or pendants, probably to be mounted side-by-side, or possibly in corresponding niches flanking a fireplace or on a symmetrically paneled wall. They depict a large American frigate hove-to off Boston Harbor, in company of a Boston pilot schooner in the course of leaving port (Pilot Pendant: Approaching (inv. 296)) or returning (Pilot Pendant: Departing (inv. 297)). The paintings have been in the same family since around 1860. According to the family, they were given to their relative Jonathan Smith by John M. Forbes sometime prior to Smith’s death in 1863. Smith was a ship’s captain, possibly for R.B. Forbes in the China trade. He contracted an illness in Shanghai and spent several years ashore working on the Forbes’ houses and yachts, for which these paintings may have been commissioned.

The scenes show a large frigate off of Boston Harbor, hove-to getting ready to receive or discharge a pilot. The frigate’s mainsails are braced aback while her other sails are drawing (except for the luffing jib), keeping the vessel stationary. It appears that Lane has depicted the same moment in both paintings, one with the bow approaching, the other astern. One can clearly see the pilot schooner’s “canoe”, used to ferry the pilot to and from the frigate, being hauled over the pilot schooner’s side in the stern view, barely visible in the bow view. The jaunty “wherry” with the small sail set in the bow view is not the pilot canoe but a device Lane inserted to further enliven the scene, along with the ubiquitous red shirt.

Interestingly, these paintings may have been commissioned to commemorate the Boston pilot schooner rather than the large frigate. The pilot schooner in both paintings flies the blue and white flag of the Boston pilots, and her hull has a shape and color scheme nearly identical to that of the schooner “Sylph” which was built as a yacht in 1834 and worked as a Boston pilot boat in 1836-37. For part of her yachting career she was owned by Robert Bennett Forbes and Samuel Cabot. It seems plausible that R. B. Forbes commissioned these paintings of his old yacht, now a pilot schooner, which were later acquired or given to his brother John Murray Forbes and hence to Jonathan Smith.

They are a handsome pair, very confidently executed by Lane, who has depicted a fresh, blowy day with scudding clouds and an active sea. As always with Lane, the rigging and details of the frigate are beautifully and correctly noted, even to the point of one of the forward jib sheets flying free shown in both views. Based on the confident, economical paint handling, these paintings likely date from the late 1840’s or early 1850’s.

–Erik Ronnberg, Sam Holdsworth

References:

1. Ralph M. Eastman, “Pilots and Pilot Boats of Boston Harbor” (Boston, MA: Second Bank – State Street Trust Company, 1956), pp. 28, 29, 31.

2. Robert Bennett Forbes, “Personal Reminiscences) (3rd. ed., rev., Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1892), Appendix: List of Vessels.

[+] See More