loading

Fitz Henry Lane

HISTORICAL ARCHIVE • CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ • EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Catalog entry

inv. 58

The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene)

Harbor Scene (Gloucester Harbor, the Fort and Ten Pound Island); Harbor Scene (The Fort and Ten Pound Island)

1848 Oil on canvas 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm) Signed and dated lower right: F H Lane / 1848

|

Related Work in the Catalog

Supplementary Images

Additional material

| Letter: Letter from poet Charles Olson to Alfred Mansfield Brooks, June 12, 1960, published in Charles Olson: Letters Home 1949-1969, edited by David Rich, published by Cape Ann Museum, 2010. [click image to enlarge] |

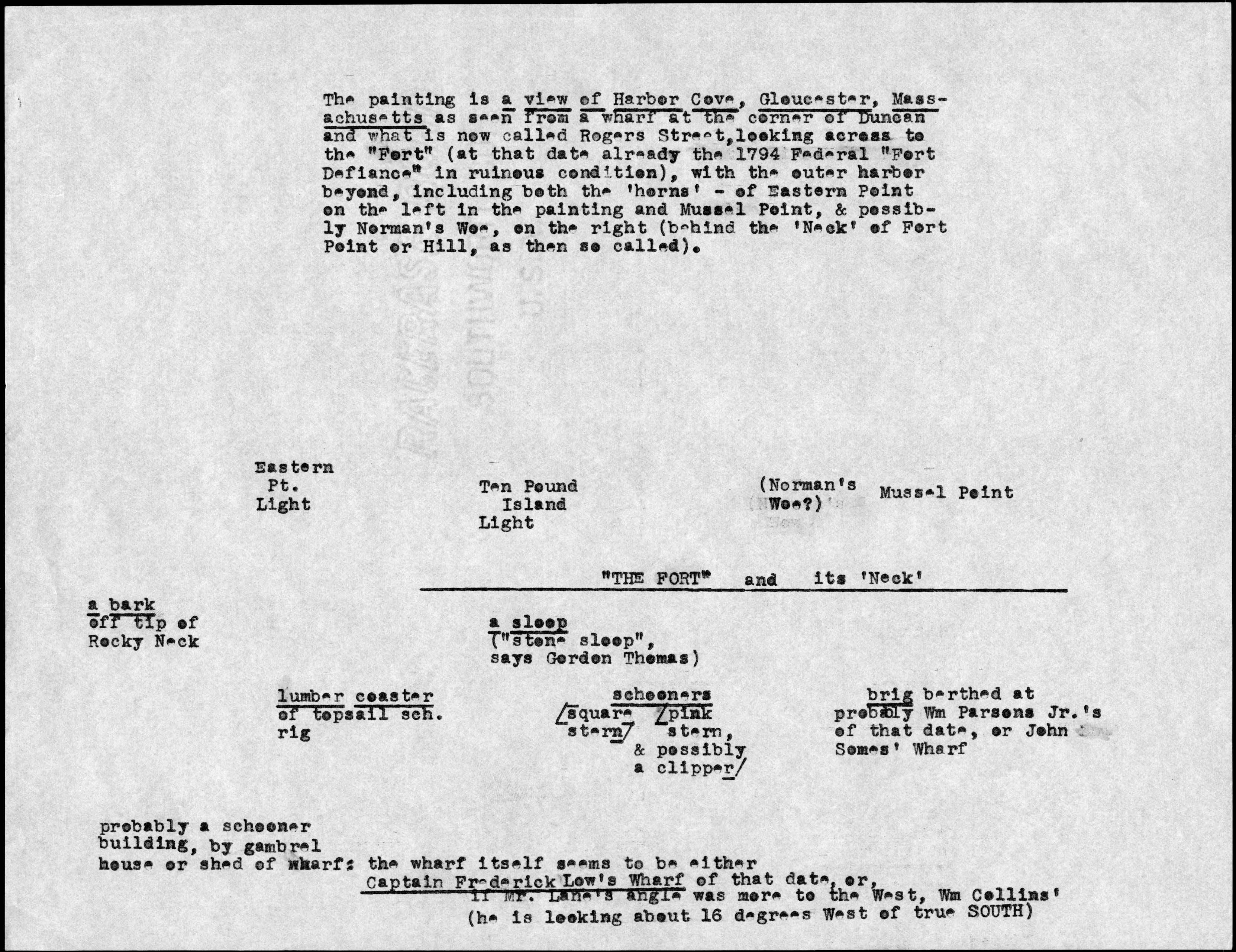

| Document: Diagram accompanying letter by poet Charles Olson to Alfred Mansfield Brooks, June 12, 1960, published in Charles Olson: Letters Home 1949-1969, edited by David Rich, published by Cape Ann Museum, 2010. [click image to enlarge] |

Provenance (Information known to date; research ongoing.)

Mrs. Chant Owen, Cheshire, Conn. (by descent)

Newark Museum, N.J., 1959

Exhibition History

Cummer Gallery of Art, Jacksonville, Florida, American Paintings of Ports and Harbors, February 4–March 16, 1969.

Traveled to: Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, Norfolk, Va., 5–11, 1969.

Traveled to: Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, Norfolk, Va., 5–11, 1969.

Whitney Museum, New York, New York, Seascape and the American Imagination, June 9–September 7, 1975.

Published References

Olson, Charles. "Letter to Alfred Mansfield Brooks (1960)." Charles Olson: Letters Home, 1949-1969. Rich, David. Gloucester: Cape Ann Museum, 2010., p. xviii. p.15, and ill. in color p.14. ⇒ includes  text

text

Wilmerding, John. Fitz Hugh Lane, 1804–1865: American Marine Painter. Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1964., p. 55.

The American Neptune, Pictorial Supplement VII: A Selection of Marine Paintings by Fitz Hugh Lane, 1804–1865. Salem, MA: The American Neptune, 1965. ⇒ includes  text

text

Dodge, Joseph Jeffers. American Paintings and Harbors, 1774–1968. Jacksonville, FL: Cummer Gallery of Art, 1969.

Wilmerding, John. Fitz Hugh Lane. New York: Praeger, 1971., pl. II.

Stein, Roger B. Seascape and the American Imagination. New York: Crown Publishers; in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1975., no. 68.

American Art in the Newark Museum: Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. Newark, NJ: The Newark Museum, 1981., p. 31.

Hoffman, Katherine. "The Art of Fitz Hugh Lane." Essex Institute Historical Collections 119 (1983)., p. 30.

Ronnberg, Erik A.R., Jr. "Imagery and Types of Vessels." In Paintings by Fitz Hugh Lane, by John Wilmerding. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1988, pp. 61–104., pp. 55–58. ⇒ includes  text

text

Labaree, Benjamin Woods. America and the Sea: A Maritime History. Mystic, CT: Mystic Seaport, 1998., p. 241.

Kugler, Richard C. William Bradford: Sailing Ships and Arctic Seas. New Bedford, MA: New Bedford Whaling Museum, in association with the University of Washington Press; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Ronnberg, Erik A.R., Jr. "William Bradford: Mastering Form and Developing a Style, 1852–1862." In William Bradford: Sailing Ships and Arctic Seas, by Richard C. Kugler. New Bedford, MA: New Bedford Whaling Museum: in association with the University of Washington Press, 2003., pp. 55–58. ⇒ includes  text

text

Slawek, Tadeusz. Revelations of Gloucester: Charles Olson, Fitz Hugh Lane, and Writing of the Place. New York: Peter Lang, 2003., Il. 6.

Ronnberg, Erik A.R., Jr. "Views of Fort Point: Fitz Hugh Lane's Images of a Gloucester Landmark." Cape Ann Historical Association Newsletter 26, no. 2–4 (April, July, September 2004)., fig. 4. ⇒ includes  text

text

Wilmerding, John. Fitz Henry Lane. Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Historical Association, 2005. Reprint of Fitz Hugh Lane, by John Wilmerding. New York: Praeger, 1971. Includes new information regarding the artist's name., pl. 2.

Commentary

When Lane returned to Gloucester in 1848, after spending approximately sixteen years in Boston as a lithographer, he painted a series of extraordinary panoramic views of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor. These views, listed below, illustrate in great detail how the harbor and all its related industries were growing and changing after a decades-long slump. In the late 1840s, a confluence of factors caused a great expansion of Gloucester’s waterfront and fishing industry. The arrival of the railroad in 1847, increased coastal trade from Maine and Canada and new fisheries, and advances in vessel design all contributed to a building boom. Gloucester Harbor was set on the trajectory that would peak fifty years later with the great age of schooner fishing.

The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene) is the only painting we know of where Lane has shown shipbuilding in process. Gloucester did not have an active shipbuilding tradition, partly because the harbor waterfront was already quite crowded. Also, the necessary timber had long ago been cleared from Cape Ann and was difficult to transport from elsewhere. The William Collins wharf was an exception, and Lane has shown all of its activity in great detail. Marine historian Erik Ronnberg has marked and identified all the elements within this painting in fascinating detail below, from the uses of the various pieces of wood and tools to the buildings and wharves in the background. Also note that Lane has signed and dated the painting in the lower right corner on the wonderful wide board fence with the pointed crenellations on top.

Lane’s lithography training is in full view in this painting. He has organized an enormous amount of detail in the foreground in a logical and spatially correct manner without it seeming cluttered. He then takes the viewer into the middle and deep distance of the harbor, where the dead calm of the summer day has slowed all motion and infused the entire painting with a sense of peace and languor at odds with the intense labor of shipbuilding. Perhaps it is lunch hour, and the two fellows chatting in the foreground will be picking up their tools shortly.

There is a feeling of nostalgia in many of these early harbor views. According to accounts of the period, many people were dismayed by the changes in the waterfront as new wharves and buildings covered up old landmarks, including the Old Fort. Lane may have felt the same way, or perhaps he was painting these pictures for an audience that did.

– Sam Holdsworth

A Visual Guide to the Painting

Foreground:

William Collins (1787 - 1845) was a blockmaker – a trade whose products included many types of wooden rigging fittings, wooden bilge pumps, and a variety of hardwood deck fittings. His products were in constant demand for new and older vessels alike, assuring a prosperous occupation. On his death, his estate was retained by his heirs and the wharf was rented out to the Burnham brothers, who not only resumed the blockmaking trade, but added shipbuilding, rigging, sparmaking, and coopering to the previous services. The Burnhams also bought out Collins’ business inventory and tools, and set up a mast-stepping crane, which can be seen in the left margin of /cat:142/.

While it cannot be documented at this time, it appears that the Burnham brothers were beginning to change their business from a combination of shipbuilding and repair to specializing in the latter, the move to Collins wharf being the initial step in what would lead to a marine railway. That facility would end Gloucester vessel owners’ reliance on hauling facilities in Boston or having to ground their vessels on a graving beach and wait for low tide to clean and repair the hull bottoms.

1. A small vessel (probably a schooner) is under construction at a stage where it is said to be “in frame." The keel has been laid and the stem post set up; framing has commenced, starting amidships and progressing to the ends.

2. Rough timbers on the ground have been chosen for making the frames. The shape of each frame part is cut from the timber whose shape matches the shape of the frame at the point where it will be joined to other parts.

3. The long, straight timbers are for spars (masts, bowsprit, booms, and gaffs). They are first cut square (in cross section) and tapered, using a broad axe; then eight-sided and sixteen-sided with a draw knife. Finally, they are made round, using a spokeshave and a plane.

4. Behind the vessel in frame is a mast-stepping crane and hoisting tackle which lifts the masts at their balance points and positions them over the vessel. On deck, a stepping gang will haul down the lower end (or heel) until the mast is vertical and positioned over the mast hole in the deck. The mast is then lowered and its heel is seated in a slot in the keelson.

5. Alongside the wharf is the recently stepped mast of a vessel hidden from view. The shrouds (lines that support the masts) were seated over the masthead before stepping and are hanging slack until the riggers set them up with deadeyes and lanyards at the vessel’s sides.

6. The cooper’s shed houses a fireplace, a very large steam kettle, and a steam box for steaming and shaping staves for barrels. The staves must be softened by the hot steam so they can be shaped to fit closely to other staves that make up the barrel. This is done by placing them in the steam box and letting them cook for an hour or more. A partially assembled barrel next to the shed shows how the finished barrels are shaped and tapered.

7. A yawl boat with damaged planking has been hauled out for repairs. Boats with blunt bows like this one needed to have their new planks steamed and softened before bending them into place.

Vessels in Harbor Cove (from left to right):

8. A bark, probably in the Surinam Trade, is tied up at Frederick G. Low’s wharf. She has probably just arrived, and preparations are under way to unload the cargo. The sails, hanging loosely to dry, will be taken ashore for washing and repairs.

9. A lumber schooner (rigged as a topsail schooner, as defined by her square fore topsails) is lowering sail and preparing to anchor while waiting for a wharfside berth in which to unload. Gloucester’s Harbor Cove was very shallow at low tide, so vessels had to wait in deeper water for high tide to move to and from wharves and anchorages. The largest ships had to anchor in deep water outside Harbor Cove and be partially unloaded by barges called lighters before going to a wharf for final loading. The deep water between Fort Point, Ten Pound Island, and Rocky Neck was then called The Stream.

10. Beyond the lumber schooner is the bottom of a schooner hulk that has been condemned as unseaworthy and stripped of metal fastenings. What is left will be used as backfill when the new wharf for George H. Rogers is built at that part of Fort Point.

11. The large sloop beyond the lumber schooner’s bow is a stone sloop—used to carry granite blocks and rubble stone from quarry wharves to places where stone piers or buildings were being constructed. This sloop is laying down rubble stone, or riprap, as a foundation for the stone bulkhead pier from which a large timber wharf will be built out.

12. Two fishing schooners are at anchor, one of which appears to be getting underway for a fishing trip. Both vessels are of conservative design and probably used for hand-line fishing from the rails—not in dories. At this period in Gloucester’s history, the fishing industry was beginning to revive after two decades of decline.

13. Near the shore, a man is moving a small New England boat by poling—nudging the boat along by pushing with the pole on the harbor bottom. The boat has possibly been repaired at Fears’ Wharf, and will be poled along the shore to the wharf where it will be outfitted for shore fishing.

14. Beyond the New England boat is a brig tied up at George H. Rogers’s old wharf at the end of Sea Street (now what is left of the lower end of Hancock Street). The brig rig was popular for ships in the earlier years of the Surinam Trade; it slowly gave way to larger barks and ships as the trade grew. Gloucester Harbor was not dredged until the twentieth century, and when ever-larger vessels were needed, the foreign trade was moved to Boston, where harbor depth was not a problem. By 1860, Gloucester’s fishing industry had the harbor virtually to itself.

15. A yawl boat is tied up to an extension of George H. Rogers’s wharf. Yawl boats were used on hand-line fishing schooners as life boats and for harbor errands. This was also true for many merchant vessels, both in coastal and foreign trades.

Fort Point land features:

16. Atop Fort Point are the remains of Fort Defiance, used for harbor defense from the mid-eighteenth century to the end of the War of 1812. Thereafter, it was allowed to crumble, prompting Gloucester citizens to help themselves to the bricks and stonework to build cellars for their new houses.

17. To the left of the fort’s remains is a small wooden building used by fishermen for stowing their gear.

18. The long white building below the fort was built by George H. Rogers, circa 1847. This was the beginning of his office, storehouse, and wharf complex, whose construction was ongoing to 1850.

19. The fish wharf of John W. Lowe is the oldest such pier on Fort Point, dating back to the eighteenth century. The stone cob wharf with the gambrel-roof buildings is the oldest part, with timber-wharf extensions and a third building added later.

20. The low land to the right was part of Pavilion Beach, which connected Fort Point to Gloucester’s mainland. It was used as a flake yard for drying salt cod on long wooden racks called fish flakes.

Outside Harbor Cove:

21. Beyond Fort Point, and partially hidden by it, is Ten Pound Island—one of two islands in Gloucester Harbor, the other named Five Pound Island. Both islands were named for the number of sheep pounds they had, not the supposed money paid for them by Cape Ann’s early settlers. The white building is Ten Pound Island Light, with the lightkeeper’s house built around it.

22. On the horizon at left is Eastern Point and its lighthouse, marking the east side of the entrance to Gloucester Harbor.

Other views of Harbor Cove:

Surviving depictions of Harbor Cove by Lane have been dated from 1842 to 1850 (with another uncataloged possibility dated circa 1851). Listed chronologically, these include:

Old Fort at Gloucester, 1842 (not published)

The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 28)

The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30)

The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271)

View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97)

The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58) (Invs. 97 and 58 use different viewing points)

Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240) (from drawing View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143))

View Across Gloucester Inner Cove, from Road near Beach Wharf, 1850s (inv. 142)

View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143)

– Erik Ronnberg