An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

inv. 271

The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts

1847 Oil on canvas 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm) Signed and dated lower right (on beam): F. H. Lane / 1847

Inscribed verso: F H Lane Gloucester / Mass. |

Related Work in the Catalog

Supplementary Images

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

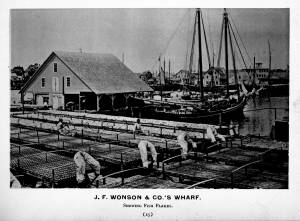

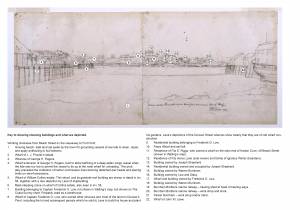

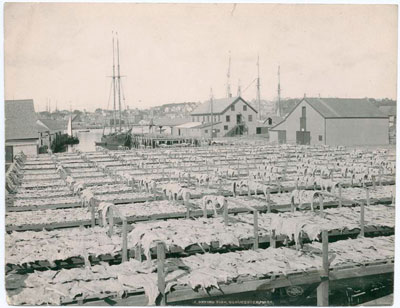

In the days prior mechanical refrigeration, salting and drying were the most common methods of preserving fish. Split cod were spread out on wooden racks, called "fish flakes," to dry. Drying time could take days, depending on weather and temperature. Warm, sunny weather could speed up the drying time, but also "burn" the fish, spoiling its texture and flavor. To prevent this, canvas awnings were stretched over wooden frames built onto the flakes. In wet weather, wooden boxes were placed over the flakes to protect them.

There were several large flake yards in Gloucester in Lane's day. One was situated between Battery Street and the beach, on the long point of land leading to the Fort, and is clearly shown in the 1851 Walling map.

c.1900.

Also filed under: Drying Fish »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Drying Fish » // Historic Photographs »

44 x 34 in.

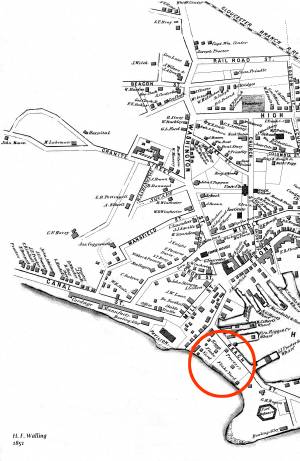

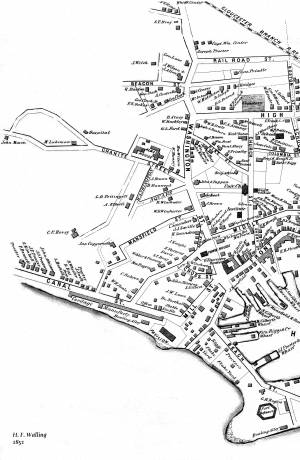

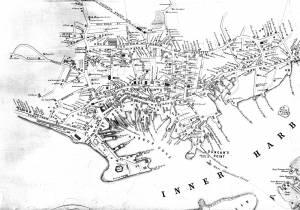

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

24 x 38 in.

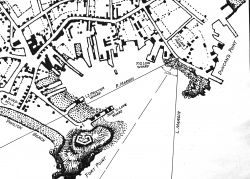

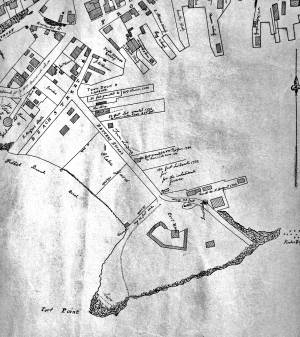

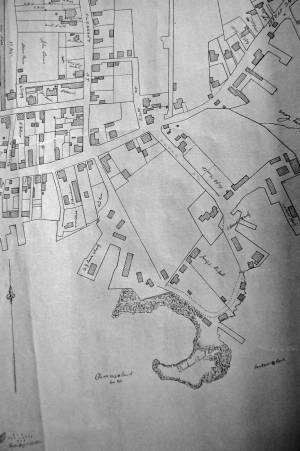

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially helpful in showing the wharves of the inner harbor at the foot of Washington Street.

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially useful in showing the Fort.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach » // Town / Public Landings »

Wood drying racks, metal split salt fish. Scale: ½" = 1' (1:24)

Original diorama components made, 1892; replacements made 1993.

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce, 1925 (2014.071)

Fish flakes are wood drying racks for salt codfish, and have been used for this purpose in America since colonial times.

Also filed under: Drying Fish »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Maps »

George H. Rogers was one of Gloucester's most enterprising citizens of the mid-nineteenth century. In the early 1830s, he ventured into the Surinam trade with great success, leading him to acquire a wharf at the foot of Sea Street. Due to Harbor Cove's shallow bottom at low tide, berthings at wharves had to be done at high tide, leaving the ships grounded at other times. Many deep-loaded vessels had to anchor outside Harbor cove and be partially off-loaded by "lighters" (shallow-draft vessels that could transfer cargo to the wharves) before final unloading at wharfside. To lessen this problem, Rogers had an unattached extension built out from his wharf into deeper water (see The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), right middle ground). The space between the old wharf and the extension may have been a way to evade harbor regulations limiting how far a pier head could extend into the harbor. Stricter rules were not long in coming after this happened!

About 1848, Rogers acquired land on the east end of Fort Point, first putting up a large three-story building adjacent to Fort Defiance, then a very large wharf jutting out into Harbor Cove. Lane's depictions of Harbor Cove and Fort Point show progress of this construction in 1848 (The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58)), 1850 (Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240)), and c.1851 (Gloucester Harbor at Dusk, c.1852 (inv. 563)). A corner of the new wharf under construction can also be seen more closely in Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 17) and Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, 1864 (inv. 104) (foregrounds). This new wharf provided better frontage for large ships to load and unload, as well as larger warehouses and lofts for storage of goods and vessel gear.

By 1860, Rogers was unloading his Surinam cargos at Boston, as ever-larger ships and barks were more easily berthed there. His Gloucester wharves continued to be used for deliveries of trade goods by smaller vessels. In the late 1860s, Rogers' wharf at Fort Point (called "Fort Wharf" in Gloucester directories) was acquired by (Charles D.) Pettingill & (Nehemiah) Cunningham for use in "the fisheries" as listed by the directory. in 1876, it was sold to (John J.) Stanwood & Company, also for use in "the fisheries." (1)

Lowe's Wharf, adjacent to Fort Wharf, was acquired by (Sylvester) Cunningham & (William) Thompson, c.1877 and used in "the fisheries" as well. That wharf and its buildings were enlarged considerably as the business grew. By this time, Harbor Cove was completely occupied by businesses in the fisheries or providing services and equipment to the fishing fleet. In photographs of Fort Point from this period, it is difficult to distinguish one business from another, so closely are they adjoined.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

1. A city atlas, dated 1899, indicates that Rogers's wharf at Fort Point was still listed as part of his estate. If so, then Stanwood & Co. would have been leasing that facility from the Rogers's estate.

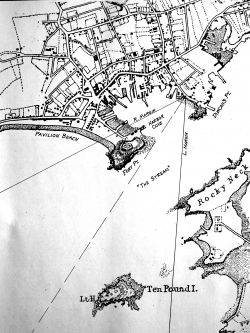

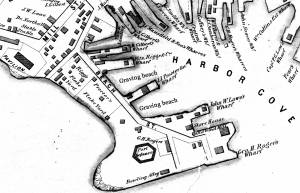

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Low's, Rogers', and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

41 x 29 inches

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives

Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Collins's, William (estate wharf) » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Maps »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

In 1849, Lane bought a small lot of land on top of a hill that jutted into Gloucester Inner Harbor. The name Duncan's Point refers alternatively to the entire hill, or only to the rocks that form a point beneath the current Coast Guard Station. The hilltop was vacant when Lane bought the property. He designed and built a gabled stone house on the hill, the northwest room of which was his studio. He lived there with his sister Sarah and her husband, Ignatius Winter, until he died in 1865, having bequeathed the house to his friend, Joseph L. Stevens, Jr. (1)

Reference:

1. Sarah Dunlop and Stephanie Buck, Fitz Henry Lane: Family and Friends (Gloucester, MA: Church & Mason Publishing; in association with the Cape Ann Historical Museum, 2007), 59–74, 150–55.

Glass plate negative

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Detail from CAHA#00279

The magnificent views of Gloucester Harbor and the islands from the top floor of the stone house at Duncan's Point where Lane had his studio were the inspiration for many of his paintings.

From Buck and Dunlop, Fitz Henry Lane: Family, and Friends, pp. 59–74.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Lane's Stone House, Duncan's Point » // Residences »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

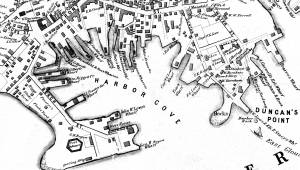

Lithograph

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Lane-Winter property on Duncan's Point.

Also filed under: Maps » // Union School » // Winter, Ignatius »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Segment shows Lane's home on Duncan's Point (as F. G. Low property) and neighboring businesses about five years after his death.

Also filed under: Maps »

Mounted print

8 x 10 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Railway at the tip of Duncan's Point. Vessels on the ways are "Isabell Leighton" and "Hattie B. West."

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

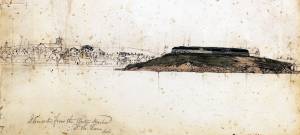

Through the years, this point and its fortifications had many names: Watch House Point, the Old Battery, Fort Defiance, Fort Head, and now just "The Fort." In 1793, Fort Defiance was turned over to the young United States government and was allowed to deteriorate. During the War of 1812 it was described as being "in ruins," and any remaining buildings burned in 1833. It was resuscitated in the Civil War and two batteries of guns were installed. The City of Gloucester did not regain ownership of the land until 1925.

The first fortifications on this point, guarding the entrance to the Inner Harbor, were put up in the 1740s, when fear of attack from the French led to the construction of a battery armed with twelve-pounder guns. Greater breastworks were thrown up in 1775, after Capt. Lindsay and his sloop-of-war the "Falcon" attacked the unprepared town. They were small and housed only a few cannon and local soldiers. Several other fortifications were at various times erected around the harbor: Fort Conant at what is now Stage Fort Park, another on Duncan's Point (near site of Lane's house) and the Civil War fort on Eastern Point. None of these preparations was ever called upon to actually defend the town.

Lane during his lifetime created a long series of images of the point and the condition of its fortifications. In 1832 there were still buildings standing, and the point had not yet been used for major wharves and warehouses. By the time of his painting Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), one can see that the earthwork foundation, but no superstructures, survived.

– Sarah Dunlap

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

Newsprint

Gloucester Telegraph

About picture of Old Fort hanging in the Gloucester Bank: "This picture is chiefly of interest on account of its preserving so accurately the features of a view so familiar to many of our citizens and which can never exist in reality."

Also filed under: Chronology » // Gloucester Bank » // Gloucester, Mass. – Gloucester Bank » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially useful in showing the Fort.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach » // Town / Public Landings »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

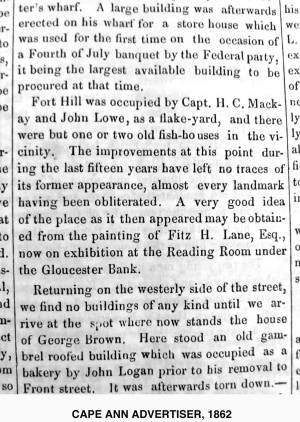

Newsprint

Cape Ann Advertiser

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Fort Hill was occupied by Capt. H. C. Mackay and John Lowe, as a flake-yard, and there were but one or two old fish-houses in the vicinity. The improvements at this point during the last fifteen years have left no traces of its former appearance, almost every landmark having been obliterated. A very good idea of the place as it then appeared may be obtained from the painting of Fitz H. Lane, Esq., now on exhibition at the Reading Room under the Gloucester Bank."

Also filed under: Gloucester Bank » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper

Gloucester Telegraph

"By the will of the late Fitz H. Lane, Esq., his handsome painting of the Old Fort, Ten Pound Island, etc., now on exhibition at the rooms of the Gloucester Maritime Insurance Co., was given to the town... It will occupy its present position until the town has a suitable place to receive it."

Also filed under: Funeral & Burial » // Gloucester, Mass. – Marine Insurance Company » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Ten Pound Island »

Newsprint

Gloucester Telegraph

At the dedication of the Town House, speaker, "read the following letter:

To the Selectmen of Gloucester: / Gents: The will of our late Townsman, Fitz. H. Lane, contains this provision: / I give to the inhabitants of the Town of Gloucester, the picture of the Old Fort, to be kept as a memento[sic] of one of the localities of olden time; the said picture now hanging in the Reading Room under the Gloucester Bank, and to be there kept until the Town of Gloucester shall furnish a suitable and safe place to hang it. / The original sketch was taken twenty-five years ago, but the boats and vessels introduced are those of a quarter of a century earlier still. The painting was executed in 1859, six years before his decease."

Also filed under: Documents / Objects » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Town House »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from top of Unitarian Church on Middle Street looking southeast, showing the Fort and Ten Pound Island. Tappan Block and Main Street buildings between Center and Hancock in foreground.

Also filed under: Ten Pound Island » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

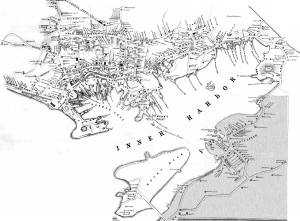

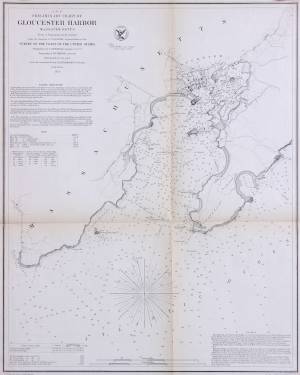

The northeast quarter of Gloucester Harbor is an inlet bounded by Fort Point and Rocky Neck at its entrance. It is further indented by three coves: Harbor Cove and Vincent’s Cove on its north side, and Smith’s Cove on its south side. The shallow northeast end is called Head of the Harbor. Collectively, this inlet with its coves and shallows is called Inner Harbor.

The entrance to Inner Harbor is a wide channel bounded by Fort Point and Duncan’s Point on its north side, and by Rocky Neck on its south side. From colonial times to the late nineteenth century, it was popularly known as “the Stream” and served as anchorage for deeply loaded vessels for “lightering” (partial off-loading). Subsequently it was known as “Deep Hole.”

Of Inner Harbor’s three coves, Harbor Cove (sometimes called “Old Harbor” in later years) was the deepest and most heavily used by fishing vessels in the Colonial Period, and largely dominated by the foreign trade in the first half of the nineteenth century. Its shallow bottom was the undoing of the foreign trade, as larger vessels became too deep to approach its wharves, and the cove returned to servicing a growing fishing fleet in the 1850s.

Vincent’s Cove, a smaller neighbor to Harbor Cove, was bare ground at low tide, and mostly useless for wharfage. Its shoreline was well suited for shipbuilding, and the cove was deep enough at high tide for launching. Records of shipbuilding there prior to the early 1860s have to date not been found.Smith’s Cove afforded wharfage for fishing vessels at its east entrance, as seen in Lane’s lithograph View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 86). The rest of the cove saw little use until the expansion of the fisheries after 1865.

The Head of the Harbor begins at the shallows surrounding Five Pound Island, extending to the harbor’s northeast end. Lane’s depiction of this area in Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23) shows the problems faced by vessel owners at low tide. Despite the absence of deep water, this area saw rapid development after 1865 when a thriving fishing industry needed waterfront facilities, even if they were accessible only at high tide.

– Erik Ronnberg

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

4 x 6 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Benham Collection

George Steele sail loft, William Jones spar yard, visible across harbor. Photograph is taken from high point on the Fort, overlooking business buildings on the Harbor Cove side.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Town House » // Universalist Church (Middle and Church Streets) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Lithograph

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Collins' and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Graving Beach »

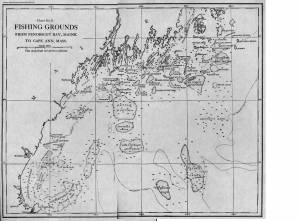

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Dolliver's Neck » // Fresh Water Cove » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Maps »

41 x 29 inches

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives

Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Collins's, William (estate wharf) » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

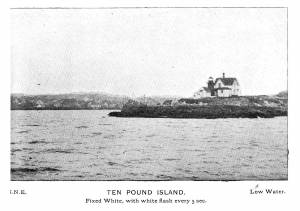

Photograph in The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, published by N. L. Stebbins, Boston

Also filed under: Beacons / Monuments / Spindles »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

From East Gloucester looking towards Gloucester.

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stereo view showing Gloucester Harbor after a heavy snowfall

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Five Pound Island and Gloucester inner harbor taken from the top of Hammond Street building signs in foreground are for Severance, Carpenter and Crane, and Cooper at Clay Cove.

Also filed under: Five Pound Island »

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Schooner (Fishing) »

Oil on canvas

34 x 45 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Mrs. Jane Parker Stacy (Mrs. George O. Stacy),1948 (1289.1a)

Detail of party boat.

Also filed under: Party Boat »

Glass plate negative

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Detail from CAHA#00279

The magnificent views of Gloucester Harbor and the islands from the top floor of the stone house at Duncan's Point where Lane had his studio were the inspiration for many of his paintings.

From Buck and Dunlop, Fitz Henry Lane: Family, and Friends, pp. 59–74.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Lane's Stone House, Duncan's Point » // Residences »

Glass plate negative

3 x 4 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

#10112

Also filed under: Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

Gloucester Outer Harbor served as a staging area for deep draft or heavily laden vessels waiting to come into the wharves in the shallow Old Harbor at high tide, or waiting to discharge cargo into smaller vessels. While Lane's paintings typically show one or two vessels in the harbor, works by other artists from the period, as well as contemporary descriptions, demonstrate that the harbor was usually crowded with vessels, especially in bad weather. The Outer Harbor could accommodate as many as three hundred vessels when they needed to shelter during a storm.

There were two deep spots where they could wait, the "Deep Hole" between Ten Pound Island and the Fort; and the "Pancake Grounds" between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. The "Pancake Grounds" also served as a quarantine area for ships arriving from foreign ports. "Deep Hole" was named for the (relatively) deep water between Rocky Neck and Fort Point to the Outer Harbor. Deeply loaded vessels had to anchor there for “lightering” (partial unloading by boats called “lighters”) prior to final unloading at wharfside. "Deep Hole" was 20–25 feet deep at low tide, when Harbor Cove was only 1–6 feet deep with bare ground around some wharves. "Deep Hole" is where you see ships anchored in Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), View of Gloucester, Mass., 1859 (not published), Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271), and Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 335) (which is coming to anchor).

The term "Deep Hole" is apparently a post-Bellum term. Prior to that, it was known as "The Stream" and, as later, served as anchorage where deeply loaded vessels could be lightered prior to docking in Harbor Cove. Alfred Mansfield Brooks in his book Gloucester Recollected uses this term on page 53. After the Civil War, merchant shipping in Gloucester was dominated by salt ships and later coal carriers, bringing a whole new culture to the harbor, and with it new names for old places.

John Heywood Photo for Hervey Friend

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooners anchored on the Pancake Ground, taken from from Wonson's Cove, easterly side of the Rocky Neck causeway. Eastern Point Fort and garrison in background to far left.

Also filed under: Eastern Point »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Rocky Neck » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from Civil War fort on Eastern Point.

Also filed under: Eastern Point » // Historic Photographs »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850: 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850: 3,213."

Also filed under: Annisquam River » // Brookbank » // Dolliver's Neck » // Fresh Water Cove » // Maps » // Norman's Woe » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head » // Steepbank » // West Gloucester – Little River » // Western Shore »

Newsprint

Cape Ann Advertiser

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Notice in the Cape Ann Advertiser announcing arrival of ships into the port of Gloucester, with details of their cargo.

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Trade Routes and Statistics »

Newspaper

"Lane's studio seldom presents so many attractions to visitors as at the present time. With unwonted rapidity his easel has turned off pictures in answer to the numerous orders which have poured in from all quarters."

Also filed under: Chronology » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Studio Descriptions »

Electrotype impression

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Maps »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head »

Pencil and ink on paper

15 x 22 1/8 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Mr. Donald K. Usher, in memory of Mrs. Margaret Campbell Usher, 1984 (2401.19)

Also filed under: Beacons / Monuments / Spindles » // Mackerel Fishing »

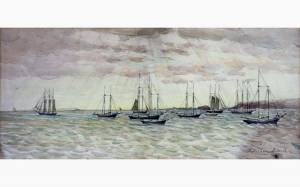

Watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 19 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Rev. and Mrs. A. A. Madsen, 1950

Accession # 1468

Fishing schooners in Gloucester's outer harbor, probably riding out bad weather.

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Schooner (Fishing) »

Ten Pound Island guards the entrance to Gloucester’s Inner Harbor and provides a crucial block to heavy seas running southerly down the Outer Harbor from the open ocean beyond. The rocky island and its welcoming lighthouse is seen, passed, and possibly blessed by every mariner entering the safety of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor after outrunning a storm at sea. Ten Pound Island is situated such that the Inner Harbor is protected from open water on all sides making it one of the safest harbors in all New England.

Legend has it that the island was named for the ten pound sum paid to the Indians for the island, and the smaller Five Pound Island deeper in the Inner Harbor was purchased for that lesser sum. None of it makes much financial sense when the entirety of Cape Ann was purchased for only seven pounds from the Indian Samuel English, grandson of Masshanomett the Sagamore of Agawam in 1700. From approximately 1640 on the island was used to hold rams, and anyone putting female sheep on the island was fined. Gloucester historian Joseph Garland has posited that the name actually came from the number of sheep pens it held, or pounds as they were called, and the smaller Five Pound Island was similarly named.

The island itself is only a few acres of rock and struggling vegetation but is central to the marine life of the harbor as it defines the eastern edge of the deep channel used to turn the corner and enter the Inner Harbor. The first lighthouse was lit there in 1821, and a house was built for the keeper adjacent to the lighthouse.

In the summer of 1880 Winslow Homer boarded with the lighthouse keeper and painted some of his most masterful and evocative watercolor views of the busy harbor life swirling about the island at all times of day. Boys rowing dories, schooners tacking in and out in all weather, pleasure craft drifting in becalmed water, seen together they tell a Gloucester story of light, water and sail much as Lane’s work did only several decades earlier.

Colored lithograph

Cape Ann Museum Library and Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light »

Photograph

From The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, N. L. Stebbins, 1891.

Also filed under: Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light »

Oil on canvas

22 x 36 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., deposited by the Collection of Addison Gilbert Hospital, 1978 (DEP. 201)

Detail of party boat.

Also filed under: Party Boat »

Engraving of 1819 survey taken from American Coast Pilot 14th edition

9 1/2 x 8 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

D32 FF5

Also filed under: Dolliver's Neck » // Eastern Point » // Maps » // Norman's Woe »

Newspaper

Gloucester Telegraph

"By the will of the late Fitz H. Lane, Esq., his handsome painting of the Old Fort, Ten Pound Island, etc., now on exhibition at the rooms of the Gloucester Maritime Insurance Co., was given to the town... It will occupy its present position until the town has a suitable place to receive it."

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from top of Unitarian Church on Middle Street looking southeast, showing the Fort and Ten Pound Island. Tappan Block and Main Street buildings between Center and Hancock in foreground.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) »

Preceded by Annisquam as the earliest permanently settled harbor and Gloucester’s original first parish, Gloucester Harbor did not become a seaport of significance until the end of the 17th century. Its earliest fishing activity was focused on nearby grounds in the Gulf of Maine, few vessels venturing further to the banks off Canada. After 1700, as maritime activity was well-established in fishing, shipbuilding, and coastal trade, the waterfront saw the expansion of flake yards for drying fish and wharves for berthing and outfitting vessels, loading lumber and fish, and receiving trade goods. Shipbuilding was also carried on, using shorelines with straight slopes not suited for wharves.

By 1740, the majority of Cape Ann-owned vessels were berthed in Gloucester Harbor; three years later, Watch House Point (now called Fort Point) was armed and fortified. The fishing fleet continued to grow, numbering over 140 vessels by the time of the Revolution. A customs office was established in 1768, resulting in strong protests over seizures of contraband. Revolution brought hardship to the fishing industry, forcing many vessel owners to resort to privateering.

Independence saw a much-diminished fishing fleet and a severely impoverished seaport. With the Federally-sponsored incentive of the codfish bounties, Gloucester fishermen began to rebuild their fishing fleet. By 1790, trade with Surinam was under way, leading to the building and purchase of merchant vessels, new wharves, and improvements to old wharves in Harbor Cove, which had become Gloucester’s center of maritime activity. In addition to shipyards and sail lofts, two ropewalks furnished cordage for rigging.

The first four decades of the 19th century saw fitful growth in the fishing industry, due to the interruptions of war and financial panics. Few wharves were added to the waterfront in that period, and when new ones were built, their purpose was to serve the growing Surinam Trade. Fishing had come to its low point in the 1840s when the railroad reached Gloucester, opening a huge inland market for the fish it caught. The use of ice to keep fish fresh, combined with new and faster fishing schooners to get it quickly to port, sparked a revival in Gloucester’s fishing industry.

As Gloucester’s fishing industry revived, its growth in the Surinam Trade was hampered by its shallow harbor which made berthing of ever larger ships more difficult. Forced to seek a deeper harbor, merchants reluctantly sent their largest ships to Boston for unloading. Between 1850 and 1860, this process continued until ships and warehouses were relocated and their owners commuted to Boston by rail, leaving their old wharves to the fishing fleet. In 1863, the Surinam trade collapsed.

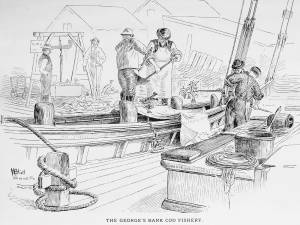

Gloucester’s fishing fleet grew dramatically in the 1850s for more reasons than ice, railroads, and faster schooners. The technology of catching fish also improved dramatically. Hand-line fishing (two hooks on a line) gave way to dory trawling with many hooks on a very long “trawl line,” while fishing for mackerel with hand-lines was replaced by “purse seining,” setting a 1,000-foot-long net in a circle around a school of mackerel. These dramatic improvements in productivity were expensive but made possible by the fishermen organizing a mutual savings bank to serve their needs and a mutual insurance company to cover their risks. These advantages could not be matched by any other fishing communities in New England or in the Canadian Maritime Provinces, sparking a huge migration of fishermen to Gloucester. These newcomers were welcomed to fill a growing work force while Gloucester’s native work force moved on to other, less dangerous, occupations.

Lane’s depictions of Gloucester’s waterfront best illustrate the period before 1850. After that date, his attention turned more to the Harbor’s outer shores, to nearby communities such as Manchester, to New York, back to Boston, and north to Maine. While his lapse of interest is regrettable, the scenes and activity he missed were becoming popular with photographers while his earlier waterfront views are nowhere else to be found.

–Erik Ronnberg

References:

Dates and happenings were based on (or confirmed by):

Mary Ray and Sarah V. Dunlap, “Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical Time-Line (Gloucester: Gloucester Archives Committee, 2002).

Improvements to Gloucester’s fishing technology, management, and financing are based on:

Wayne O’ Leary, “Maine Sea Fisheries” (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), pp. 166–179 (fishing technology), 235–251 (management and financing), and 235–251 (in-migration to Gloucester).

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Windmill »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Windmill »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This view of Gloucester's Inner Harbor shows three square-rigged vessels in the salt trade at anchor. The one at left is a (full-rigged) ship; the other two are barks. By the nature of their cargos, they were known as "salt ships" and "salt barks" respectively. Due to their draft (too deep to unload at wharfside) they were partially unloaded at anchor by "lighters" before being brought to the wharves for final unloading.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Bark / Barkentine or Demi-Bark » // Historic Photographs » // Salt »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stereo view showing Gloucester Harbor after a heavy snowfall

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Wood, metal, and paint

20 1/4 x 10 1/4 x 10 1/2 in., scale: 1/2" = 1'

Made for the Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892–93

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce

The wharf is built up of "cribs", square (sometimes rectangular) frames of logs, resembling a log cabin, but with spaces between crib layers that allow water to flow freely through the structure.Beams are laid over the top crib, on which the "deck" of the wharf is built. Vertical pilings (or "spiles" as locally known) are driven at intervals to serve as fenders where vessels are tied up.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Cob / Crib Wharf »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

In general, brigs were small to medium size merchant vessels, generally ranging between 80 and 120 feet in hull length. Their hull forms ranged from sharp-ended (for greater speed; see Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43)) to “kettle-bottom” (a contemporary term for full-ended with wide hull bottom for maximum cargo capacity; see Ships in Ice off Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 44) and Boston Harbor, c.1850 (inv. 48)). The former were widely used in the packet trade (coastwise or transoceanic); the latter were bulk-carriers designed for long passages on regular routes. (1) This rig was favored by Gloucester merchants in the Surinam Trade, which led to vessels so-rigged being referred to by recent historians as Surinam brigs (see Brig "Cadet" in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s (inv. 13) and Gloucester Harbor at Dusk, c.1852 (inv. 563)). (2)

Brigs are two-masted square-rigged vessels which fall into three categories:

Full-rigged brigs—simply called brigs—were fully square-rigged on both masts. A sub-type—called a snow—had a trysail mast on the aft side of the lower main mast, on which the spanker, with its gaff and boom, was set. (3)

Brigantines were square-rigged on the fore mast, but set only square topsails on the main mast. This type was rarely seen in America in Lane’s time, but was still used for some naval vessels and European merchant vessels. The term is commonly misapplied to hermaphrodite brigs. (4)

Hermaphrodite brigs—more commonly called half-brigs by American seamen and merchants—were square-rigged only on the fore mast, the main mast being rigged with a spanker and a gaff-topsail. Staysails were often set between the fore and main masts, there being no gaff-rigged sail on the fore mast.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 64–68.

2. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 62–74. A candid and witty view of Gloucester’s Surinam Trade, which employed brigs and barks.

3. R[ichard] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman's Friend (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1841. 13th ed., 1873), 100 and Plate 4 and captions; and M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 95.

4. Parry, 95, see Definition 1.

Oil on canvas

17 1/4 x 25 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Isabel Babson Lane, 1946 (1147.a)

Photo: Cape Ann Museum

Detail of brig "Cadet."

Also filed under: "Cadet" (Brig) »

Painting on board

72 x 48 in.

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

Chart showing the voyage of the brig Cadet to Surinam and return, March 10–June 11, 1840.

Also filed under: "Cadet" (Brig) » // Surinam Trade »

The colonial American shallop is the ancestor of many regional types of New England fishing craft found in Lane's paintings and drawings, including "New England Boats" (known as "boats" and discussed elsewhere), and later descendents, such as "Chebacco Boats," "Dogbodies," and "Pinkies."

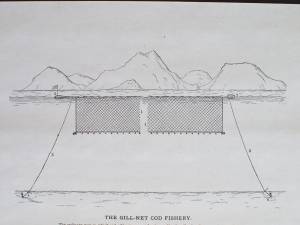

These boats were very common work boat types on Cape Ann throughout the 1800s. They were primarily used for inshore coastal fishing, which included lobstering, gill-netting, fish-trapping, hand-lining, and the like. They were usually sailed by one or two men, sometimes with a boy, and could be rowed as well as sailed. An ordinary catch would include rock cod, flounder, fluke, dabs, or other small flat fish. The catch would be eaten fresh, or salted and stored for later consumption, or used as bait fish. Gill-netting would catch herring and alewives when spawning. Wooden lobster traps were marked with buoys much as they are today, and hauled over the low sides of the boat, emptied of lobsters and any by-catch, re-baited and thrown back.

CHEBACCO BOATS AND PINKIES

In the Chebacco Parish of the Ipswich Colony, a larger version of the colonial shallop evolved to a heavily built two-masted boat with either a sharp or square stern. This development included partial decking at bow and stern, the former as a cuddy which was fitted with crude bunks and a brick fireplace for cooking. Further development provided midship decking over a fish hold with standing rooms fore and aft for fishing. At this stage, low bulwarks replaced simple rails and in the double-enders were extended aft beyond the rudderhead to form a “pinched,” or “pink“ stern. Some time in the second half of the eighteenth century, boats with these characteristics became known as Chebacco Boats. The squarestern versions were called Dogbodies, for reasons now forgotten. (1)

Chebacco Boats became the vessels of choice for Cape Ann fishermen working coastal grounds for cod, mackerel, herring, and groundfish with hook and line or with nets. This did not prevent them from venturing further, particularly in pursuit of migrating schools of mackerel. The “Bashalore,” a corruption of the Bay of Chaleur in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, was a favorite destination for Cape Ann Fishermen who fished for mackerel in that region. (2)

Lane undoubtedly saw Chebacco Boats in the years prior to his move to Boston, but if he made drawings or paintings of them in that period, none have come to light. A small lithograph, titled “View of the Old Fort and Harbor 1837,” is attributed to him, but the vessels and wharf buildings are too crudely drawn to warrant this undocumented claim. (3) Lane did see and render accurately the Chebacco Boat’s successor the Pinky—which was larger and had a schooner rig (two masts, main sail, fore sail, jib, and main topmast staysail).

Schooners with pinksterns were recorded early in the 18th century later that there were models and graphic representations of hull form and rig (Ref. 4). By then, the pinky was very similar in hull form to Chebacco Boats, and some Chebacco Boats were converted to pinkies by giving them schooner rigs. A pinky in Lane’s The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30) (misdated 1850s, more likely mid-1840s) is quite possibly an example of such a conversion.

Lane’s depictions of pinkies in Massachusetts waters are numerous and sometimes very informative. Examples in his views of Gloucester Harbor portray them at various angles, from broadside (see Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), and View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 86)) to stern (see The Western Shore with Norman's Woe, 1862 (inv. 18), The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), and Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 391)), but few, if any, bow views. His portrayals of pinkies in Boston Harbor and vicinity are more in the foreground and more generous in detail. The earliest of these, from 1845, shows a pinky getting underway in a hurry as the yacht "Northern Light" bears down on her in The Yacht "Northern Light" in Boston Harbor, 1845 (inv. 268). A late harbor view (id ) offers a rare bow view.

Like the Chebacco Boat, the pinky was primarily a fishing vessel, doing much the same kind of fishing in coastal waters, but large enough to venture further offshore to work on the banks in the Gulf of Maine in pursuit of the cod. By the 1820s, pinkies reached their largest size: 50 to 60 feet on deck. Beyond that size called for a different deck arrangement and higher rails, so men could stand on deck and fish from the rails – an arrangement offered by the banks fishing schooner. (5)

What is perhaps Lane’s most detailed and narrative view of a pinky appears in Becalmed Off Halfway Rock, 1860 (inv. 344) and dominates the right foreground. Fitted-out for mackerel gillnetting, she has a dory and a wherry in tow, the latter with the net in the stern. The crew is relaxed, enjoying the evening calm as the vessel heads for port. The barrels on deck are filled with freshly caught mackerel, which will be sold as such when landed, most likely at Gloucester. This pinky was probably fishing on Stellwagen Bank or Cape Cod Bay, which were good fishing grounds for mackerel, and close enough to Gloucester to make trips in smaller vessels worthwhile. To judge from his paintings, Lane found only a few pinkies in the parts of the Maine Coast he explored. Only one drawing (Southwest Harbor, Mount Desert, 1852 (inv. 184)) and two widely published paintings (Entrance of Somes Sound, Mount Desert, Maine, 1855 (inv. 347) and Bar Island and Mt. Desert Mountains from Somes Settlement, 1850 (inv. 401)) illustrate this type, and then at a distance. What is apparent is that pinkies in southern Maine did not differ markedly from those on the Massachusetts coast. Had Lane ventured further Down East, he might have found modifications to the type that reflected Canadian influences. (6)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. William A. Baker, Sloops & Shallops (Barre, MA: Barre Publishing Co., 1966), 82–91; and Howard I. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners, 1825–1935 (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 25–27.

2. G. Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, Section V, Vol. I (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1884–87), 275, 287, 298–300, 419–21, 425–32, 459–63.

3. John J. Babson, History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann (Procter Bros., 1860, reprint: Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1972), see lithograph facing p. 474.

4. Goode, 275–77, 280, 294–96.

5. Chapelle, 36–37.

6. Ibid., 45–54.

Glass plate negative

3 x 4 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

#10112

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

Also filed under: Ship Models »

Also filed under: Ship Models »

Also filed under: Ship Models » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

20" l. x 19" h. x 3 3/4" w. [not to scale]

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Mr. J. Hollis Griffin, 1940 (891)

"Pinkys" were early nineteenth-century schooner-rigged derivations of Chebacco boats. This model is a good example of a traditional “sailor’s model,” or in this case, a sailmaker’s model, Mr. Nickerson having been a sailmaker.

Also filed under: Ship Models »

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

The colonial American shallop is the ancestor of many regional types of New England fishing craft found in Lane's paintings and drawings, including "New England Boats" (known as "boats"), and later descendents, such as "Chebacco Boats," "Dogbodies," and "Pinkies." (discussed elsewhere)

These boats were very common work boat types on Cape Ann throughout the 1800s. They were primarily used for inshore coastal fishing, which included lobstering, gill-netting, fish-trapping, hand-lining, and the like. They were usually sailed by one or two men, sometimes with a boy, and could be rowed as well as sailed. An ordinary catch would include rock cod, flounder, fluke, dabs, or other small flat fish. The catch would be eaten fresh, or salted and stored for later consumption, or used as bait fish. Gill-netting would catch herring and alewives when spawning. Wooden lobster traps were marked with buoys much as they are today, and hauled over the low sides of the boat, emptied of lobsters and any by-catch, re-baited and thrown back.

THE SHALLOP

Like other colonial vessel types, shallops were defined in many ways, including size, construction, and rig. Most commonly, they were open boats with square or sharp sterns, 20 to 30 feet in length, two-masted rigs, and heavy sawnframe construction which in time became lighter. (1)

The smaller shallops developed into a type called the Hampton Boat early in the nineteenth century, becoming the earliest named regional variant of what is now collectively termed the New England Boat. Other variants were named for their regions of origin: Isles of Shoals Boat, Casco Bay Boat, No Mans Land Boat, to name a few. No regional name for a Cape Ann version has survived, and "boat," or "two-masted boat" seems to have sufficed. (2)

Gloucester's New England Boats were mostly double-enders (sharp sterns) ranging in length from 25 to 30 feet, with two masts and two sails (no bowsprit or jib). They were used in the shore fisheries: handlining, gillnetting, and gathering or trapping shellfish (see View from Kettle Cove, Manchester-by-the-Sea, 1847 (inv. 94), View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97), and /entry: 240/). (3)

Larger, double-ended shallops became decked and evolved in Ipswich (the part now called Essex) to become Chebacco Boats. (4) This variant retained the two-mast, two-sail rig, but evolved further, acquiring a bowsprit and jib and becoming known as a pinky (see Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), The Western Shore with Norman's Woe, 1862 (inv. 18), and The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30)). The Chebacco Boat became a distinct type by the mid-eighteenth century giving rise to the pinky in the early ninetennth century; the latter, by the early 1900s. (5)

References:

1. William A. Baker, Sloops & Shallops (Barre, MA: Barre Publishing Co., 1966), 27–33; and “Vessel Types of Colonial Massachusetts,” in Seafaring in Colonial Massachusetts (Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1980), 13–15, see figs. 10, 11.

2. Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 136–45.

3. Ibid., 145, upper photo, fourth page of plates.

4. Baker, 82–91.

5. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners, 1825–1935 (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 23–54.

THE NEW ENGLAND BOAT

By the 1840s, the Gloucester version of the New England Boat had evolved into a distinct regional type. Referred to locally as “boats,” the most common version was a double-ender, i.e. having a pointed stern, unlike the less common version having a square stern.

Both variants had two masts, a foresail, a mainsail, but no bowsprit or jib. Lane depicted both in several paintings, beginning in the mid-1840s (see View from Kettle Cove, Manchester-by-the-Sea, 1847 (inv. 94), View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97), and /entry: 240/), all ranging 25 to 30 feet in length. In View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97) and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), a double-ender can be seen on the beach while a square-stern version lies at anchor in the harbor, just to the right of the former. (1)

Lane’s depictions of the double-enders show lapstrake hull planking in View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97) and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), and cuddies (short decking) inboard at the ends for shelter and stowage of fishing gear in View from Kettle Cove, Manchester-by-the-Sea, 1847 (inv. 94). The few square-stern examples (see View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97) and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240)) suggest carvel (smooth) planking and paint finish, rather than oil and tar. The presence of an example of the latter variant in Boston Harbor, as noted in Boston Harbor, c.1850 (inv. 48), suggests a broader geographical range for this subtype. (2)

The primary use of Cape Ann’s “boats” was fishing, making “day trips” to coastal grounds for cod, herring, mackerel, hake, flounder, and lobster, depending on the season. Fishing gear included hooks and lines, gill nets, and various traps made of wood and fish net.

Some boats worked out of Gloucester Harbor, but other communities on Cape Ann had larger fleets, such as Sandy Bay, Pigeon Cove, Folly Cove, Lanesville, Bay View, and Annisquam. Lane’s depictions of these places and their boats are rare to nonexistent. (3)

The double-ended boat served Lane in marking the passage of time in Gloucester Harbor. In View from Kettle Cove, Manchester-by-the-Sea, 1847 (inv. 94), we see new boats setting out to fish, but in View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97) and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), a boat of the same type is depicted in a progressively worn state. In Stage Fort across Gloucester Harbor, 1862 (inv. 237), the boat is a stove hulk on a beach, and in the same year, Lane depicted the type’s shattered bottom frame and planking lying on the shore at Norman’s Woe in Norman's Woe, Gloucester Harbor, 1862 (inv. 1).

Regional variants of the New England Boat appear in Lane’s paintings of Maine harbors, including one and two-masted versions, collectively called Hampton Boats (see Bear Island, Northeast Harbor, 1855 (inv. 24), Ten Pound Island at Sunset, 1851 (inv. 25), Fishing Party, 1850 (inv. 50), Father's (Steven's) Old Boat, 1851 (inv. 190), and "General Gates" at Anchor off Our Encampment at Bar Island in Somes Sound, Mount Desert, Maine, 1850 (inv. 192)). Some distinctive regional types were given names, i.e. Casco Bay Boats ("General Gates" at Anchor off Our Encampment at Bar Island in Somes Sound, Mount Desert, Maine, 1850 (inv. 192) may be one), but many local type names, if they were coined, have been lost. (4)

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 141–42.

2. Ibid., 152–55.

3. Sylvanus Smith, Fisheries of Cape Ann (Gloucester, MA: Press of the Gloucester Times, 1915), 96–97, 102–05, 110–13.

4. Chapelle, 152–55.

Also filed under: Ship Models »

Also filed under: Ship Models »

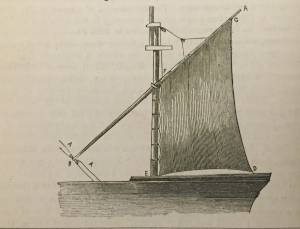

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) oncargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Fishing Schooners: While the port of Gloucester is synonymous with fishing and the schooner rig, Lane depicted only a few examples of fishing schooners in a Gloucester setting. Lane’s early years coincided with the preeminence of Gloucester’s foreign trade, which dominated the harbor while fishing was carried on from other Cape Ann communities under far less prosperous conditions than later. Only by the early 1850s was there a re-ascendency of the fishing industry in Gloucester Harbor, documented in a few of Lane’s paintings and lithographs. Depictions of fishing schooners at sea and at work are likewise few. Only A Smart Blow, c.1856 (inv. 9), showing cod fishing on Georges Bank (4), and At the Fishing Grounds, 1851 (inv. 276), showing mackerel jigging on Georges Bank, are known examples. (5)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 74–76.

5. Howard I. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 58–75, 76–101.

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

Stereograph card

Frank Rowell, Publisher

stereo image, "x " on card, "x"

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View showing a sharpshooter fishing schooner, circa 1850. Note the stern davits for a yawl boat, which is being towed astern in this view.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Model made for marine artist Thomas M. Hoyne

scale: 3/8" = 1'

Thomas M. Hoyne Collection, Mystic Seaport, Conn.

While this model was built to represent a typical Marblehead fishing schooner of the early nineteenth century, it has the basic characteristics of other banks fishing schooners of that region and period: a sharper bow below the waterline and a generally more sea-kindly hull form, a high quarter deck, and a yawl-boat on stern davits.

The simple schooner rig could be fitted with a fore topmast and square topsail for making winter trading voyages to the West Indies. The yawl boat was often put ashore and a "moses boat" shipped on the stern davits for bringing barrels of rum and molasses from a beach to the schooner.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seafarers in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 29–31.

Also filed under: Hand-lining » // Ship Models »

20 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

The image, as originally drafted, showed only spars and sail outlines with dimensions, and an approximate deck line. The hull is a complete overdrawing, in fine pencil lines with varied shading, all agreeing closely with Lane's drawing style and depiction of water. Fishing schooners very similar to this one can be seen in his painting /entry:240/.

– Erik Ronnberg

Newspaper

"Shipping Intelligence: Port of Gloucester"

"Fishermen . . . The T. [Tasso] was considerably injured by coming in contact with brig Deposite, at Salem . . ."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

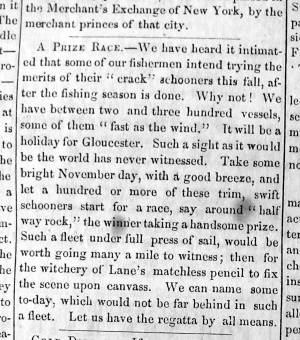

Newsprint

From bound volume owned by publisher Francis Procter

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"A Prize Race—We have heard it intimated that some of our fishermen intend trying the merits of their "crack" schooners this fall, after the fishing season is done. Why not! . . .Such a fleet under full press of sail, would be worth going many a mile to witness; then for the witchery of Lane's matchless pencil to fix the scene upon canvass. . ."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Also filed under: Cape Ann Advertiser Masthead »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Rocky Neck » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

See p. 254.

As Erik Ronnberg has noted, Lane's engraving follows closely the French publication, Jal's "Glossaire Nautique" of 1848.

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester »

Wood, cordage, acrylic paste, metal

~40 in. x 30 in.

Erik Ronnberg

Model shows mast of fishing vessel being unstepped.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Fishing »

Watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 19 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Rev. and Mrs. A. A. Madsen, 1950

Accession # 1468

Fishing schooners in Gloucester's outer harbor, probably riding out bad weather.

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Print from bound volume of Gloucester scenes sent to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

11 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

Schooner "Grace L. Fears" at David A. Story Yard in Vincent's Cove.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Shipbuilding / Repair » // Vincent's Cove »

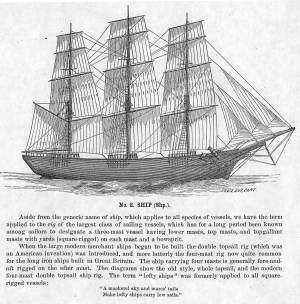

The term "ship," as used by nineteenth-century merchants and seamen, referred to a large three-masted sailing vessel which was square-rigged on all three masts. (1) In that same period, sailing warships of the largest classes were also called ships, or more formally, ships of the line, their size qualifying them to engage the enemy in a line of battle. (2) In the second half of the nineteenth century, as sailing vessels were replaced by engine-powered vessels, the term ship was applied to any large vessel, regardless of propulsion or use. (3)

Ships were often further defined by their specialized uses or modifications, clipper ships and packet ships being the most noted examples. Built for speed, clipper ships were employed in carrying high-value or perishable goods over long distances. (4) Lane painted formal portraits of clipper ships for their owners, as well as generic examples for his port paintings. (5)

Packet ships were designed for carrying capacity which required some sacrifice in speed while still being able to make scheduled passages within a reasonable time frame between regular destinations. In the packet trade with European ports, mail, passengers, and bulk cargos such as cotton, textiles, and farm produce made the eastward passages. Mail, passengers (usually in much larger numbers), and finished wares were the usual cargos for return trips. (6) Lane depicted these vessels in portraits for their owners, and in his port scenes of Boston and New York Harbors.

Ships in specific trades were often identified by their cargos: salt ships which brought salt to Gloucester for curing dried fish; tea clippers in the China Trade; coffee ships in the West Indies and South American trades, and cotton ships bringing cotton to mills in New England or to European ports. Some trades were identified by the special destination of a ship’s regular voyages; hence Gloucester vessels in the trade with Surinam were identified as Surinam ships (or barks, or brigs, depending on their rigs). In Lane’s Gloucester Harbor scenes, there are likely (though not identifiable) examples of Surinam ships, but only the ship "California" in his depiction of the Burnham marine railway in Gloucester (see Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, 1857 (inv. 29)) is so identified. (7)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. R[ichard)] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman’s Friend, 13th ed. (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1873), p. 121 and Plate IV with captions.

2. A Naval Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884), 739, 741.

3. M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World’s Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 536.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 281–87.

5. Ibid.

6. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 26–30.

7. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 67–69.

Photograph

From American Clipper Ships 1833–1858, by Octavius T. Howe and Frederick C. Matthews, vol. 1 (Salem, MA: Marine Research Society, 1926).

Photo caption reads: "'Golden State' 1363 tons, built at New York, in 1852. From a photograph showing her in dock at Quebec in 1884."

Also filed under: "Golden State" (Clipper Ship) »

Oil on canvas

24 x 35 in.

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

Walters' painting depicts the "Nonantum" homeward bound for Boston from Liverpool in 1842. The paddle-steamer is one of the four Clyde-built Britannia-class vessels, of which one is visible crossing in the opposite direction.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Packet Shipping » // Walters, Samuel »

The term “wherry”—variously spelled—has a long history with many hull types, some dating from the fifteenth century. (1) The version known to Lane appears to be a variant of the dory hull form and probably was developed by French and English fishermen in the Newfoundland fisheries before 1700. (2) From that time, the wherry and the dory co-evolved, their similarities the result of their construction, their differences the result of use. By the early nineteenth century, their forms reached their final states, if fragments of contemporary descriptions are any indication. (3)

By the time Lane was depicting wherries, the type (as used for fishing) resembled a larger, wider version of a dory. The extra width was due to greater bottom width (both types had flat bottoms), with a wider transom at the stern instead of the narrow, v-shaped “tombstone.” These features are easy to see in one of his drawings (see Three Men, One in a Wherry (inv. 225)) and a painting (see Sunrise through Mist, 1852 (inv. 98)), the latter depicted alongside a dory, clearly showing the differences.