An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Supplementary Images

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

The beach between Stage Rocks and Tablet Rocks, adjacent to Fisherman's Field, was known during Lane's time as either Field Beach or Long Beach. It was a bit more rocky than Half Moon Beach. After Lane's time it became known as Crescent (or Cressy's) Beach. Field Rocks are just off the shore of the beach.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stage Fort from Hough's Farm, showing a panorama of the harbor from Pavilion Beach to Fort Point and Rocky Neck.

Also filed under: Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head »

Newspaper

"Mr. Lane has just completed a third picture of the Western Shore of Gloucester Harbor, including the distance from 'Norman's Woe Rock' to 'Half Moon Beach.' It was painted for Mr. William E. Coffin of Boston, and will be on exhibition at the artist's rooms for only a few days; we advise all our readers who admire works of art, and would see one of the best pictures Mr. Lane has ever executed..."

"...solitary pine, so many years a familiar object and landmark to the fisherman."

Also filed under: Coffin, William E. » // Dolliver's Neck » // Fresh Water Cove » // Half Moon Beach » // Lone Pine » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Norman's Woe » // Studio Descriptions »

Letter

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

". . . will fully appreciate all that I have done in my garden, in ornamenting it, with flowers and plants, Rustic Arbours and Statues, and I only wish that you could be here to witness and enjoy his [Dr. J. L. Stevens] expressions of delight and interest, when a new flower attracts his attention, or some beauty of arrangement meets his eye. Samuel [B. Stevens of Castine] he tells me came up with the expectation of going on a voyage to Australia, but when he arrived in Boston he found the vessel with her compliment of men, and it is very uncertain if he goes in her. Your Mother and all at home are well. I yesterday made a sketch of Stage Fort and the surrounding scenery, from the water. Piper has given me an order for a picture from this point of view, to be treated as a sunset. I shall try to make something out of it, but it will require some management, as there is no foreground but water and vessels. One o’clock, it is very hot, the glass indicates 84° in my room, with the windows all open and a light breeze from the east, this is the warmest day . . .

. . . than devoting it to you. Since writing you last I have painted but one picture worth talking about and that one I intend for you if you should be pleased with it. It is a View of the beach between Stage Fort and Steep bank including Hovey’s Hill and residence, Fresh water cove and the point of land with the lone pine tree. Fessenden’s house, likewise comes into the picture. The effect is a mid day light with a cloudy sky, a patch of sunlight is thrown across the beach and the breaking waves, an old vessel lies stranded on the beach with two or three figures, there are a few vessels in the distance and the Field rocks likewise show at the left of the picture. I think you will be pleased with this picture, for it is a very picturesque scene especially the beach, as there are many rocks which come in to destroy the monotony of a plain sand beach, and I have so arranged the light and shade that the effect I think is very good indeed, however you will be better able to judge of that when you see it, the size is 20 x 33. . ."

Commonwealth of Massachusetts: Southern Essex District Registry of Deeds

1543 plan 0141_0001

The third of the three plans has the references on it “Plan showing the taking of land, flats and beach for Stage Fort Park…1898…”

Includes a reference to the home of Mary Turnbull which is Steepbank.

Also filed under: Maps » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head » // Steepbank »

29 x 25 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (#089)

Ernest Bowditch was a landscape gardener. This map shows some of the various names of landmarks around Stage Rocks.

Also filed under: Half Moon Beach » // Maps » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head »

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) on cargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Coasting schooners: This is the most general term, applied to any merchant schooner carrying cargo from one coastal port to another along the United States coast (see Bar Island and Mt. Desert Mountains from Somes Settlement, 1850 (inv. 401), right foreground). (4)

Packet schooners: Like packet sloops, these vessels carried passengers and various higher-value goods to and from specific ports on regular schedules. They were generally better-maintained and finished than schooners carrying bulk cargoes (see The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), center; and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), stern view). (5)

Lumber schooners: Built for the most common specialized trade of Lane’s time, they were fitted with bow ports for loading lumber in their holds (see View of Southwest Harbor, Maine: Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 260)) and carried large deck loads as well (Stage Rocks and the Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857 (inv. 8), right). Lumber schooners intended for long coastal trips were often rigged with square topsails on their fore masts (see Becalmed Off Halfway Rock, 1860 (inv. 344), left; Maverick House, 1835 (not published); and Lumber Schooner in a Gale, 1863 (inv. 552)). (6)

Schooners in other specialized trades. Some coasting schooners built for carrying varied cargoes would be used for, or converted to, special trades. This was true in the stone trade where stone schooners (like stone sloops) would be adapted for carrying stone from quarries to a coastal destination. A Lane depiction of a stone schooner is yet to be found. Marsh hay was a priority cargo for gundalows operating around salt marshes, and it is likely that some coasting schooners made a specialty of transporting this necessity for horses to urban ports which relied heavily on horses for transportation needs. Lane depicted at least two examples of hay schooners (see Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 391), left; and Coasting Schooner off Boon Island, c.1850 (inv. 564)), their decks neatly piled high with bales of hay, well secured with rope and tarpaulins.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 40, 42–43.

5. Ibid., 42–43, 73.

6. Ibid., 74–76.

A topsail schooner has no tops at her foremast, and is fore-and-aft rigged at her mainmast. She differs from an hermaphrodite brig in that she is not properly square-rigged at her foremast, having no top, and carrying a fore-and-aft foresail instead of a square foresail and a spencer.

Wood rails, metal rollers, chain; wood cradle. Scale: ½" = 1' (1:24)

Original diorama components made, 1892; replacements made, 1993.

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce, 1925 (2014.071)

A schooner is shown hauled out on a cradle which travels over racks of rollers on a wood and metal track.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Marine Railways »

Glass plate negative

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Lobstering »

Details about Maine's lumber trade in 1855, see pp. 250–52

Also filed under: Castine » // Lumber Industry »

The yawl boat was a ninteenth-century development of earlier ships' boats built for naval and merchant use. Usually twenty feet long or less, they had round bottoms and square sterns; many had raking stem profiles. Yawl boats built for fishing tended to have greater beam than those built for vessels in the coastal trades. In the hand-line fisheries, where the crew fished from the schooner's rails, a single yawl boat was hung from the stern davits as a life boat or for use in port. Their possible use as lifeboats required greater breadth to provide room for the whole crew. In port, they carried crew, provisions, and gear between schooner and shore. (1)

Lane's most dramatic depictions of fishing schooners' yawl-boats are found in his paintings Gloucester Outer Harbor, from the Cut, 1850s (inv. 109) and /entry:311. Their hull forms follow closely that of Chapelle's lines drawing. (2) Similar examples appear in the foregrounds of Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), Ships in Ice off Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 44), and The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271). A slightly smaller example is having its bottom seams payed with pitch in the foreground of Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23). In Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), a grounded yawl boat gives an excellent view of its seating arrangement, while fishing schooners in the left background have yawl boats hung from their stern davits, or floating astern.

One remarkable drawing, Untitled (inv. 219) illustrates both the hull geometry of a yawl boat and Lane's uncanny accuracy in depicting hull form in perspective. No hull construction other than plank seams is shown, leaving pure hull form to be explored, leading in turn to unanswered questions concerning Lane's training to achieve such understanding of naval architecture.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 222–23.

2. Ibid., 223.

Oil on canvas

12 1/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M.and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865 (48.447)

A schooner's yawl lies marooned in the ice-bound harbor in this detail.

Prior to marine railways, the only way to clean and repair a vessel’s bottom was to bring it as far ashore on a sandy beach as tide would allow, then wait as the tide ebbed, leaving the vessel high and dry. Tidal amplitude (the difference between high tide and low tide) ranged between nine feet and twelve feet on Cape Ann (neap tide and spring tide), allowing reasonable working time for vessels drawing seven to ten feet. This was suitable for most fishing schooners and smaller craft, but larger vessels would need the services of marine railways, graving docks, or “heaving-down” facilities in larger ports. (Ref. 1)

The most desirable graving beaches had clean, firmly-packed sand with rock-free areas large enough to accommodate local vessels. Gloucester’s Harbor Cove had such a beach along its south-west side which was actually the part of Pavilion Beach which faced the cove. Two of Lane’s depictions of Harbor Cove (View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97) and The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271)) show this beach in their far right backgrounds, with schooners grounded out and men working on them.

The term “graving” also applied to docks fitted at one end with watertight gates which, when closed, allowed the dock to be pumped dry so a docked vessel could be worked on at all hours. Such facilities are commonly called “dry docks” and were found in Boston, Portsmouth, New York, and other large ports with major merchant or naval facilities. (Ref. 2)

–Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. “A Naval Encyclopaedia” (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884. Reprint: 1971), p. 318.

2. “The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History” (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), Vol. 1, p. 571.

44 x 34 in.

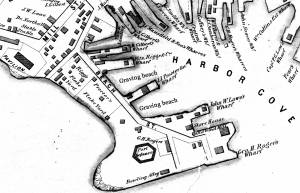

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Collins' and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

To judge from Lane's depictions of Gloucester Harbor, It would seem that the harbor was devoid of shipbuilding activity, with only one painting The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58) showing a vessel under construction. While the historical record shows far more shipbuilding activity in nearby Essex, Gloucester did have significant shipbuilding in the years 1800 to 1865, amounting to 93 registered vessels and an unknown number of enrolled vessels. The registered vessels included 82 schooners, four (full-rigged) ships, one bark, four brigs, and two sloops. The numbers of enrolled vessels is unknown, but they were likely to be smaller craft with sloop and schooner rigs, and built in significant numbers. (1)

Official records were compiled by the U.S. Customs Service for all merchant and fishing vessels, registry being applied to vessels trading or fishing in foreign waters and ports. "Enrolment" (as spelled on customs documents) was applied to vessels fishing or trading only in U.S. territorial waters. Registry documents were filed with the Register of the Treasury in Washington, DC, as well as with the local customs offices. Enrollment documents were filed only with local customs offices and were subject to loss due to fires or careless storage, leaving many voids in the record of American coastal fishing and shipping. (2)

Shipbuilding was a time-consuming process, needing a sizeable space for lofting, millwork, storage of shipbuiding timbers and lumber, not to mention the building- and launching ways. Prime waterfront space was not a necessity. As long as the launching incline is straight, and the water is deep enough to float the vessel at high tide, the building site can utilize unwanted shoreline, as it did in Gloucester's Vincent Cove for many years. The likelihood that Gloucester shipyards were in out-of-the-way places around the Inner Harbor is probably why Lane (and his clientele) paid so little attention to them.

The vessel in Lane's painting is probably a very small schooner—more likely to be enrolled than registered. Building vessels on a wharf was common in Gloucester, even into the twentieth century, but launching was difficult for larger vessels. The example in Lane's painting will probably measure (not weigh) about twenty tons - a small vessel which should be easy to launch this way. Needless to say, the launching would take place at high tide, when the drop from wharf to water was minimal.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789-1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944)

2. Forrest R. Holdcamper, "Registers, Enrollments and Licenses in the National Archives", The American Neptune 1, no. 3, 275–83.

Print from bound volume of Gloucester scenes sent to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

11 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

Schooner "Grace L. Fears" at David A. Story Yard in Vincent's Cove.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Vincent's Cove »

Details about Maine's shipbuilding industry, see pp. 252–57.

Also filed under: Castine »

The Practical Ship-Builder: Containing the Best Mechanical and Philosophical Principles for the Construction Different Classes of Vessels, and the Practical Adaption of their Several Parts, with Rules Carefully Detailed. Collins Keese & Co, New York, 1839. Oblong 4to, 17x20 cm, (2), 107, (4) pp, ill., 7 fold. plates.

In Google Books

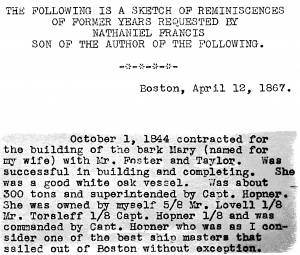

"October 1, 1844 contracted for the building of the bark Mary (named for my wife) with Mr. Foster and Taylor. Was successful in building and completing. She was a good white oak vessel. Was about 300 tons and superintended by Capt. Hopner. She was owned by myself 5/8 Mr. Lovell 1/8 Mr. Torsleff 1/8 Capt. Hopner 1/8 and was commanded by Capt. Hopner who as as I consider one of the best ship masters that sailed out of Boston without exception. . . .We sailed the bark Mary for three years after making three successful voyages, taking each about one year going from Boston to Norfolk and to Rio and St. Petersburg and Boston and then sold her to Wm. H. Boadman for the sum of $16,500 being about what she cost when new and she had about paid for herself."

Also filed under: "Mary" (Bark) »

Commentary

This view of Gloucester Harbor is from the western shore at Field Beach, near its eastern end with the rocks of Stage Fort at the left margin. This site can be termed a “graving beach,” having no large rocks buried in the sand which could damage hull bottoms when they were high and dry at low tide. Prior to the marine railways, this was the standard method of cleaning and repairing hull bottoms on Cape Ann and nearby harbors.

The activity in this scene is confined to mending plank seams and “pitching” (tarring) the hull bottom. The former activity has already been completed; the caulkers have packed their tool bags and left. What is here depicted is the process of “pitching the bottom” with hot pitch and a crude brush resembling a broom. In this scene, one man tends the tar pot, keeping its contents hot and easier to brush on. A second man is chopping wood to keep the fire going, while a third applies the hot pitch to the bottom planking.

This process proceeded with the tides, the work stopping when the tide rose and resuming when it ebbed. This activity was depicted by Lane in another harbor scene Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23), while graving beaches not in use can be seen in a drawing View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143) and a lithograph View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 437).

The two schooners in the middle ground are coasting schooners, probably anchored for a day or two to take on water before resuming their voyages. The yawl boat with passengers may be bringing friends of the captain alongside for a visit and exchange of news. Another yawl boat at the shore awaits a crew member, his gear on his back, to return to one of the schooners. The ship in the background is a merchantman in the deep-water trade, returning from Surinam or Europe. Lane’s depiction of small craft was as painstaking as that of his larger vessels. One can count the frames in the bow of the yawl boat in the left foreground.

– Erik Ronnberg

[+] See More