An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

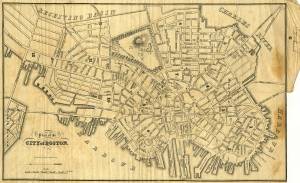

inv. 92

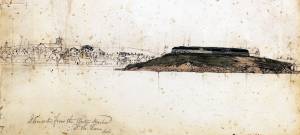

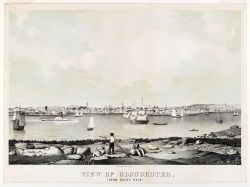

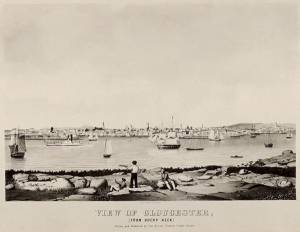

View of Gloucester, (From Rocky Neck)

View of Gloucester from Rocky Neck; View of Gloucester, Mass.; View of Gloucester, Massachusetts

1846 Colored lithograph 21 1/2 x 35 1/2 in. (54.6 x 90.2 cm) Printed under image lower center: Lane & Scott Lithography / VIEW OF GLOUCESTER, / (From Rocky Neck).

Collections:

|

Related Work in the Catalog

Supplementary Images

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

44 x 34 in.

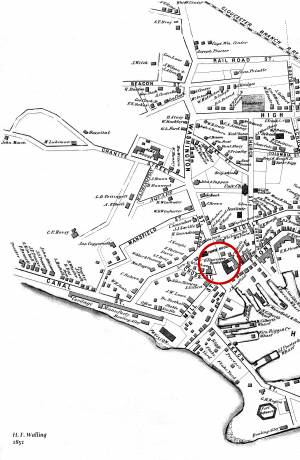

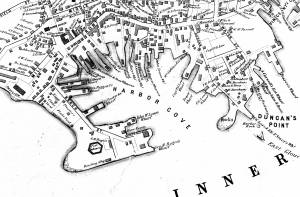

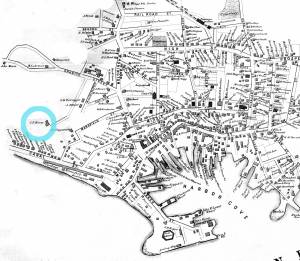

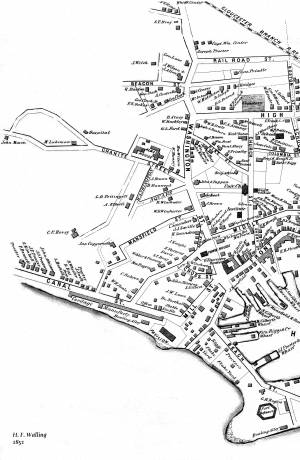

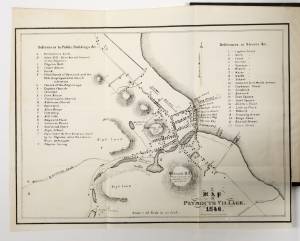

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

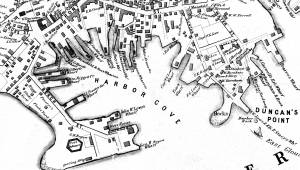

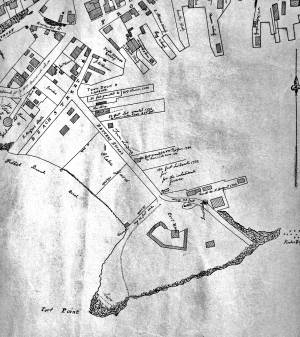

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Low's, Rogers', and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

Unknown Newspaper

"Our fellow townsman, Mr. Fitz H. Lane, has just published a splendid Lithographic view of Gloucester, which we think is far superior to his former one. It is one of the most perfect pictures of the kind we have ever seen, every house and object being distinctly visible. Copies of it can be obtained at Mr. Charles Smith's Bookstore, at the reasonable price of $1."

Filed under: Lithography (Sales & Exhibitions) » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper

Cape Ann Light & Gloucester Telegraph, p.3 col. 3

Boston Public Library

Accession # G56115

"Lane's new View of Gloucester, set in elegant Black Walnut or Gilt Frames at the store of C. Smith, 32 Front street, Gloucester. It makes a splendid Picture- every family that can afford it should have one."

Filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Four-page letter

Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

"[The painting] is offered you for $150 on as long time and in as many notes at 3% interest as you choose. . . I believe this to be the only important painting of Gloucester Harbor that Lane never duplicated. . . .Returning from a Gloucester visit while I was still under the roof there, father brought a print of Lane's first Gloucester view, bought of the artist at his Tremont Temple studio in Boston. An extra dollar had been paid for coloring it. For a few years it was a home delight.. . .I had been a few years in Gloucester when Lane began to come, for part of the time a while, if I remember rightly. He painted in his brother's house, "up in town" it then was. I recall visits there to see his pictures. But it was long after, that I could claim more than a simple speaking acquaintance. The Stacys were very kind, aiding him as time went on in selling paintings by lot. I invested in a view of Gloucester from Rocky Neck, thus put on sale at the old reading room, irreverently called "Wisdom Hall." And they bought direct of him to some extent, before other residents. Lane was much my senior and yet we gradually drifted together. Our earliest approach to friendship was after his abode began in Elm Street as an occupant of the old Prentiss [sic-corrected Stacy] house, moved there from Pleasant. I was a frequenter of this studio to a considerable extent, yet little compared with my intimacy at the next and last in the new stone house on the hill. Lane's art books and magazines were always at my service and a great inspiration and delight—notably the London Art Journal to which he long subscribed. I have here a little story to tell you. A Castine man came to Gloucester on business that brought the passing of $60 through my hands at 2 1/2 % commission. I bought with the $1.50 thus earned Ruskin's Modern Painters, my first purchase of an artbook. I dare say no other copy was then owned in town. . . .Lane was frequently in Boston, his sales agent being Balch who was at the head of his guild in those days. So in my Boston visits – I was led to Balch's fairly often – the resort of many artists and the depot of their works. Thus through, Lane in various ways I was long in touch with the art world, not only of New England but of New York and Philadelphia. I knew of most picture exhibits and saw many. The coming of the Dusseldorf Gallery to Boston was an event to fix itself in one's memory for all time. What talks of all these things Lane and I had in his studio and by my fireside!

For a long series of years I knew nearly every painting he made. I was with him on several trips to the Maine coast where he did much sketching, and sometimes was was [sic] his chooser of spots and bearer of materials when he sketched in the home neighborhood. Thus there are many paintings whose growth I saw both from brush and pencil. For his physical infirmity prevented his becoming an out-door colorist."

Colored lithograph

21 1/2 x 35 1/2 in.

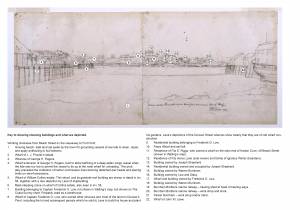

Detail of Ignatius Webber's windmill, without vanes.

Filed under: Windmill »

The old Baptist church appears in several Lane works. This was the first of three Baptist churches built on Pleasant Street. Baptists had been meeting on Cape Ann since 1808, originally in Sandy Bay (Rockport). But in 1830, a small group of Gloucester Baptists raised the funds to build a simple, unornamented, steeple-less white wooden building and chose this site near Franklin Square. Lane lithographs and paintings document the history of the building. In 1836, he showed it without a steeple. The building was improved in 1837 with the addition of a choir and the steeple, as seen in Lane's 1844 painting.

The building was not a church at the time of the painting of Gloucester Harbor in 1852, where it can be seen between the square four-spiked steeple of the First Parish Church and the mast of the closest, central boat. The Baptists, having recently built the large Italianate church seen just to the right in that 1852 painting, had sold the old Baptist church to Benjamin S. Corliss and other neighbors in 1850. Then in 1855, the Catholic community of Gloucester bought and moved the old church building around the corner to Prospect Street. The first Catholic mass had been held in 1849, in a private home, although the town hall was also available for masses. By 1855, the Catholic community established St. Ann's Parish, first in the old Baptist building (once again without a steeple, probably lost during the move from Pleasant Street), and then, when the current large stone church was built in 1876, this building became a school. It was replaced by the still-standing brick St. Ann's Parochial School in 1913.

– Sarah Dunlap (August, 2013)

Newspaper clipping

Cape Ann Advertiser

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"LANE'S PAINTINGS were distributed on Saturday last among the subscribers, as follows: Harbor Scene, – Thaddeus Friend. View of Bear Island, – George Marsh. Good Harbor Beach, – Mrs. J. H. Stacy. Fancy Sketch, – Capt. Charles Fitz. Scene at Town Parish, – J. H. Johnson, Salem. Beach Scene, – Pattillo & Center. View near Done Fudging, – Ripley Ropes, Salem."

Also filed under: Alex Patillo Dry Goods » // Center & Co. » // Center, Henry » // Done Fudging » // Fitz, Capt. Charles » // Friend, Thaddeus » // Johnson, J. H. » // Marsh, George » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Patillo, Alex » // Ropes, Ripley » // Stacy, Mr. and Mrs. John Hancock »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

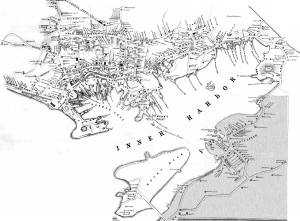

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

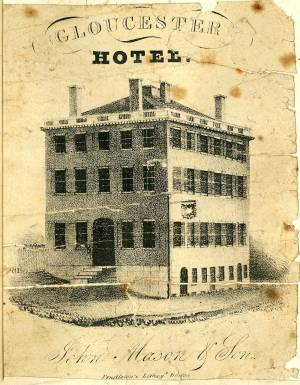

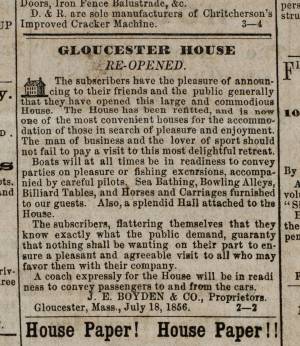

The Brick Houses were a cluster of buildings and a center of commerce and residence for wealthy local merchants. The brick hotel, the Gloucester House, was built by Col. James Tappan in 1810. It was four stories high, and scoffers of his grandiose hopes called it Tappan's Folly. It was from this hotel that stage coaches, before the 1847 extension of railroad to Gloucester, left for Boston every morning at 7:00 and returned every afternoon at 4:00. The hotel was opened year round, and was used by tourists and business people, as well as by local organizations. The John Mason family owned the hotel since the 1820s, and John's son Sidney Mason was the proprietor. Lane had perhaps already made an advertisement lithograph of this hotel in 1836. Sidney Mason also built the elaborate and luxurious summer Pavilion Hotel directly on the beach of the Outer Harbor. Both hotels are prominent in Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), and perhaps therefore the reason why Sidney commissioned Lane to paint that view. Col. Abijah Peabody, "one of the best landlords in the country," managed both hotels in 1852. Through the years, this brick hotel has also been named the Atlantic House, the Mason House, the Puritan House, and Blackburn Tavern. It still stands, offering a basement restaurant and upstairs public rooms.

The Gloucester House was the only brick building in the West End of town at the time of the disastrous fire on September 16, 1830, that wiped out blocks of wooden buildings and wharves. The brick buildings to the south and east of the Gloucester House replaced houses destroyed by that fire. Fire was an ever-present fear to Lane, who limped and walked with some difficulty. The story of the burning at sea of a merchant vessel on May 26, 1830, caught his attention, and the young artist, still Nathaniel Rogers Lane, painted Burning of the Packet Ship "Boston", 1830 (inv. 82) soon thereafter. A few months later, Lane, 26, lame and still living at home, experienced the panic and destruction of the September fire. His family's house on Middle Street was in danger, but survived intact. In 1849, after Lane returned to Gloucester from his lithography years in Boston, he built a fire-resistant stone house on Duncan's Point.

These brick houses were inhabited by wealthy merchants, owners of the wharves and businesses, next to the Town Landing and the intersection of Washington and Front Streets. Among them were Samuel Gilbert, James Mansfield, and Cyrus and Zachariah Stevens. Zachariah Stevens was the grandfather of Lane's friend and future executor, Joseph L. Stevens, Jr. Joseph lived with Zachariah from 1840 until his grandfather's death in 1846. Although still in Boston during this time, Lane frequently returned to his family and friends in Gloucester, and the two probably often met in the grandfather's house. Joseph and Lane made frequent trips to Joseph's parents' home in Castine, Maine.

Current address: West End of Main Street.

– Sarah Dunlap (August, 2013)

Stereo view

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Newsprint

Ad for Gloucester House

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.

See p. 4, column 2.

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Party Boat »

William Collins likely inherited his father's blockmaking business in 1810, including a shop and the wharf at the head of Harbor Cove. Blockmaking, which included the making of various types of rigging fittings (blocks, deadeyes, belaying pins, cleats, etc.) called for skilled workmanship and use of special types of wood. Inventories and auction announcements for William Collins’ estate give long lists of tools, materials, and products from his business. (Ref. 1)

Maps of the harbor from 1835 identify the wharf as Collins property, one of them being labeled “Wm. Collins”, suggesting sole ownership by then. When William Collins died in 1845, the property remained in the hands of his family, as indicated in Walling’s map of Cape Ann (1851) and in the Commissioner’s Map of Gloucester Harbor (1865).

Collins’ death did not mean the end of his wharf’s use in his line of work. An announcement in "The Gloucester Telegraph" that year stated that Parker Burnham & Brothers would resume the blockmaking business on the wharf, along with sparmaking and carpentry. All those activities were associated not just with shipbuilding, but with vessel maintenance and repair. They possibly marked the beginning of a major change in the Burnhams’ business, which had focused on shipbuilding to this point, but was now shifting to vessel repairs, and would lead to their building Gloucester’s first marine railway half a decade later.(Ref. 3)

–Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. “Gloucester Telegraph”, April 2, 1845. Administrator’s Sale, April 9, 10 o’clock, Wm. P. Dolliver, Adm’r. Massachusetts Archives, Probate Records, Essex County, March 1845.

2. Henry F. Walling, “Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex County, Massachusetts” (Philadelphia: A. Kollner, 1851). “Commissioners” Map of Gloucester Harbor, Massachusetts” (Commissioners on Harbors and Flats of the Commonwealth, October, 1865).

3. “Gloucester Telegraph”, May 7, 1845. “Removal”, Parker Burnham & Brothers, Gloucester, April 23, 1845.

Newspaper announcement

Gloucester Telegraph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

AUCTION

ADMINISTRATOR’S SALE

ON WEDNESDAY, April 9th, 10 o’clock Workshop of Wm. Collins (deceased) near Willam Burnham’s, will be sold. ALL the STOCK, TOOLS. &c. &c., of said shop,

Consisting in part as follows, About 400 Blocks of different sizes; 600 unfinish-ed Blocks; lot of Lignumvita Belaying Pins; Jib Hanks; Hand Pumps; 2 Guns; Handspikes; Knives; 1 large Grindstone; Saws; Gouges; Chisels; Planes; Augers; Bitt Stocks and Bitts; 1 Turning Lathe; 2 Vices; Stove and Funnel; Crow Bars; Hammer and Drills; Wheelbarrow; 2 large New Purchase Blocks; 2 second hand do. do.; together with a variety of other articles too numerousto mention.

Also, a SAIL BOAT

Wm. P. DOLLIVER, Adm’r.

If it should be foul weather, the sale will take

Place the first fair day after. March 29

Also filed under: Collins, William » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper announcement

Gloucester Telegraph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

REMOVAL.

The Subscribers have taken the Wharf of the Late Mr. Wm. Collins, where they will keep a large assortment of good BLOCKS, MAST HOOPS, JIB HANKS, Hand and Vessel PUMPS, and all articles made in a Block Maker’s Shop. Blocks repaired and Well Pumps made at short notice. They will also carry on Spar making with their Carpentering business.

PARKER BURNHAM & BROTHERS.

Gloucester, April 23, 1845

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

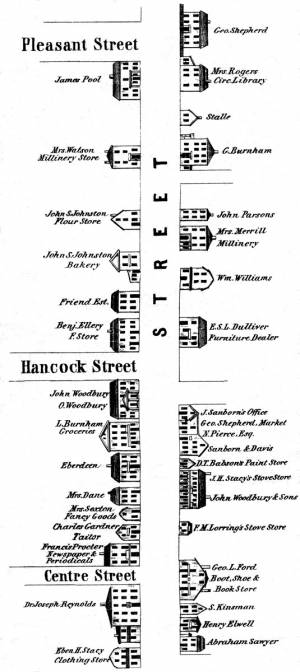

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Collins' and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

41 x 29 inches

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives

Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

High Street is the old name for the west end of what is now Prospect Street. Originally, it was Back Street, to go with Middle and Front Streets. Front Street became Main Street. Middle Street is still Middle Street. Back Street became High Street, and then adopted the name Prospect Street which already had gone from Pleasant Street east.

– Sarah Dunlap

Glass plate negative from Benham Collection

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View of Gloucester Harbor from Friend Street Wharves, Five Pound Island segment at far left, Rocky Neck, Eastern Point and Ten Pound Island in background.

Also filed under: Eastern Point » // Five Pound Island »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Gloucester Bank » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Stacy, Eben Hough »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Looking east down Main Street after storm of April 5, 1861; Centre Street enters from the left at "Job Printing" and John C. Calef, dry goods shop is on the right. (Buck and Dunlap, p. 97).

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // J. C. Calef Dry Goods »

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Maps » // Procter Brothers »

Oil on canvas

15 x 24 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Harold and Betty Bell, 1980 (2211)

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Town House »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Sawyer Free Library »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

From East Gloucester looking towards Gloucester.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Half Moon Beach » // Historic Photographs » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head » // Steepbank »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

1775–1875 Gloucester's Centennial, August 9th. Stereoscopic views of the celebration.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"In the foreground is a clear sheet of water which washes upon the beach beyond. The Pavilion is quite prominent, while upon the rising background can be seen the steeples of the several churchs, the tower of the first Town House, and the Collins School House."

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Pavilion Hotel » // Stage Rocks / Stage Fort / Stage Head »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Bond's Hill is a high eminence on the west side of Gloucester Harbor. The foreground is very rocky and shows a portion of the old road to West Gloucester and Essex, used before the road was built across the marsh, which is to be seen in the center of the picture. Beyond the marsh road is the canal with its dyke. Then the ground rises and dwelling houses appear, till Lookout Hill (or Mount Vernon Street.) can be seen on the left of the background. On the right of the picture is the 'Cut' road, the only carriage entrance into the main part of the town. Beyond it is to be seen 'Crescent Beach,' with the Pavilion and 'old Fort' and a portion of East Gloucester in the background. In the centre of the picture can be seen the unfinished tower of the Town House, and in the distance is the open sea, with Thatcher's Island and its lighthouses just discernible."

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Pavilion Hotel »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View shows Main Street Fish Market, Gloucester, Mass.

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs »

This was Charles F. Hovey's new house when Lane painted Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), the hilltop house on the horizon at the far left of the canvas, above the Fort. It is identified as the C.F. Hovey house on the 1851 Walling map and stood high above the outer Harbor, overlooking Gloucester's waterfront. The house that Charles Hovey built has been greatly altered by several owners over the years, but still commands an impressive view of the surrounding sea and land.

The brothers Charles Fox Hovey and George Otis Hovey, sons of Darius and Sarah, were born in Brookfield, Massachusetts. They first appeared in the Gloucester Assessor's Valuations in 1846, when Charles had a house, barn and land worth the substantial sum of $3,000, and George had land and an unfinished house worth $1,000, the beginnings of a vast estate on Dolliver’s Neck, Fresh Water Cove. The brothers enrolled in the Gloucester militia in 1847.

By 1851, both Charles and George lived in Boston, although they continued to own and pay taxes on their Gloucester houses. Charles was an abolitionist of note and a supporter of the women's rights convention. Charles F. Hovey died in Boston on April 28, 1859 of rheumatic gout. The posthumous $50,000 Hovey Fund was managed and allocated by the abolitionist and reformer, Wendell Phillips. George was a merchant and died in Gloucester on July 18, 1877.

Current address: 6 Hovey Street.

– Sarah Dunlap (January, 2014)

In the 1850s, Captain Frederick G. Low owned fully one-third of the land comprising Duncan's point, including the lot purchased by Lane for his home and studio. Much of his property fronted the Inner Harbor, including two wharves in Harbor Cove and a third jutting southeast from the point toward Harbor Rock (see Walling & Hanson map below.)

Low's wharves are not conspicuous in any of Lane's depictions of Gloucester Harbor, which is ironic because many of his harbor scenes were sketched from Low's property. In The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), his wharf adjacent to the Collins estate wharf is obscured by a building on the Collins wharf and a ship tied up to his own wharf. In Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), his wharf extending to Harbor Rock is concealed by the rocks off Fort Point with only a bark to mark the head of the wharf to which it is tied up.

Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), depicting the town from Rocky Neck, is the only painting which shows the shore line where Lowe's wharves were located (or to be located, given the early, 1844, date of this work). Lane's lithograph of 1846 (View of Gloucester, (From Rocky Neck), 1846 (inv. 57)) is similarly problematic, and his 1859 version (View of Gloucester, Mass., 1859 (not published)) shows so many changes that the earlier wharves are no longer discernible.

– Erik Ronnberg

Watercolor on paper

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Maps » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

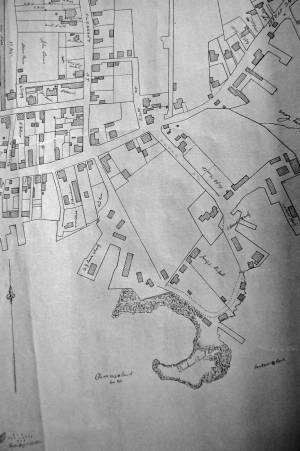

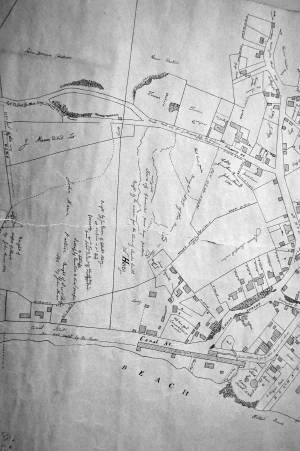

Lithograph

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Low's, Rogers', and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

George H. Rogers was one of Gloucester's most enterprising citizens of the mid-nineteenth century. In the early 1830s, he ventured into the Surinam trade with great success, leading him to acquire a wharf at the foot of Sea Street. Due to Harbor Cove's shallow bottom at low tide, berthings at wharves had to be done at high tide, leaving the ships grounded at other times. Many deep-loaded vessels had to anchor outside Harbor cove and be partially off-loaded by "lighters" (shallow-draft vessels that could transfer cargo to the wharves) before final unloading at wharfside. To lessen this problem, Rogers had an unattached extension built out from his wharf into deeper water (see The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), right middle ground). The space between the old wharf and the extension may have been a way to evade harbor regulations limiting how far a pier head could extend into the harbor. Stricter rules were not long in coming after this happened!

About 1848, Rogers acquired land on the east end of Fort Point, first putting up a large three-story building adjacent to Fort Defiance, then a very large wharf jutting out into Harbor Cove. Lane's depictions of Harbor Cove and Fort Point show progress of this construction in 1848 (The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58)), 1850 (Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240)), and c.1851 (Gloucester Harbor at Dusk, c.1852 (inv. 563)). A corner of the new wharf under construction can also be seen more closely in Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 17) and Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, 1864 (inv. 104) (foregrounds). This new wharf provided better frontage for large ships to load and unload, as well as larger warehouses and lofts for storage of goods and vessel gear.

By 1860, Rogers was unloading his Surinam cargos at Boston, as ever-larger ships and barks were more easily berthed there. His Gloucester wharves continued to be used for deliveries of trade goods by smaller vessels. In the late 1860s, Rogers' wharf at Fort Point (called "Fort Wharf" in Gloucester directories) was acquired by (Charles D.) Pettingill & (Nehemiah) Cunningham for use in "the fisheries" as listed by the directory. in 1876, it was sold to (John J.) Stanwood & Company, also for use in "the fisheries." (1)

Lowe's Wharf, adjacent to Fort Wharf, was acquired by (Sylvester) Cunningham & (William) Thompson, c.1877 and used in "the fisheries" as well. That wharf and its buildings were enlarged considerably as the business grew. By this time, Harbor Cove was completely occupied by businesses in the fisheries or providing services and equipment to the fishing fleet. In photographs of Fort Point from this period, it is difficult to distinguish one business from another, so closely are they adjoined.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

1. A city atlas, dated 1899, indicates that Rogers's wharf at Fort Point was still listed as part of his estate. If so, then Stanwood & Co. would have been leasing that facility from the Rogers's estate.

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Low's, Rogers', and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

41 x 29 inches

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives

Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Collins's, William (estate wharf) » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Maps »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Thomas Sanders built the house in 1764. For many years it was the home of John Beach, owner of a ropewalk that extended from Middle Street to almost Prospect. John Beach, Jr. was the creator of an image of an angel that adorned the pulpit at the Universalist Church at the other end of Middle Street. At the time of Lane's painting, the house was owned by the Davidson family. Dr. Herman E. Davidson was a prominent doctor in town, and his home was frequently visited by Lane. It was in this house that Lane spent many Sunday afternoons, and where he sought refuge when life in his Stone House was too disrupted by disputes with his brother-in-law, Ignatius Winter. Here it was, also, that Lane had the dream of the image of the dismasted and beached vessel, after which he drew a sketch for his hostess, Mrs. Sarah M. Davidson, and later created the famous Dream Painting, 1862 (inv. 74).

This house became the Gloucester Lyceum and Sawyer Free Library in 1884. Lane had been a member of the Gloucester Lyceum from the early 1840s, joining while he still lived principally in Boston. Once he moved back to Gloucester, he became a director. During Lane's life, the Lyceum met at 2 Spring (Main) Street, near the present the intersection of Duncan Street and not far from Lane's Stone House, built in 1849–50 on Duncan's Point. Samuel Sawyer, a wealthy businessman, philanthropist and patron of the arts, bought the elegant Sanders-Davidson house and gardens in 1884, and immediately donated it to the City for use as a library. The Library and Lyceum were thereafter placed in the center of the civic life of Gloucester, between the Unitarian Church on Middle Street and the 1871 City Hall on the newly-laid-out Dale Avenue.

Current Address: 88 Middle Street, Sawyer Free Library, corner Middle Street and Dale Avenue.

– Sarah Dunlap (October, 2013)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Middle Street looking west. At the corner of Dale Avenue is the Sanders-Davidson house, later Sawyer Free Library. Also shown: Unitarian Church, Congregational Church.

Also filed under: Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

The Trinity Congregational Church, visible in Lane paintings such as Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), was built in 1831, during the time of the reconstruction of downtown Gloucester after the devastating 1830 fire. But this church was not built to replace one lost in that conflagration. It was built to house a large faction of the original First Parish Church (the four -pointed square tower visible in several paintings, just to the east on Middle Street) that was dismayed by the Unitarian drift of the parish. The rise of Unitarianism, and the hiring of new ministers with that leaning, caused those who continued to embrace the older Puritan, Calvinist, Congregational beliefs to secede and form their own church. It was a split between the more radical, newer element of the Unitarians and those who wished to maintain their older, Trinitarian roots.

The minister of the Trinitarian church in 1852 was James Aiken, who did not stay in town long. Nor did the building serve long as a church. In 1854, the building was sold, cut in half, and moved. Both halves now stand on Mason Street, facing south, across School Street from the Central Fire Station.

A second Trinity Congregational Church, with a steeple higher than any other in town, was immediately erected on same site in 1854. This 153-foot, octagonal steeple, visible in Gloucester from Steepbank, c.1855 (inv. 125) was removed in 1865. The church building was totally destroyed by fire in July 1979. A third church stands on the site today.

Current address: 70 Middle Street at the corner of School Street. However, the building that appears in pre-1854 Lane works was cut in half and moved to 2–8 Mason Street.

– Sarah Dunlap (August, 2013)

On Middle St., the building of the new Orthodox Church will soon be commenced. …we understand that the church when completed, will be the finest in the country. It is to be surmounted by a steeple higher than any other in town, and will be a prominent land mark. The contractors, Messrs. Smith & Babson, are young and enterprising mechanics, and will spare no pains to render the completion of the edifice as perfect and handsome as can be accomplished. The old church having been cut in two, and moved back on Mason Street, is being fitted up, and will be made into two large double dwelling houses. Another building has also been moved into this street and is being fitted up for a dwelling house.

The First Parish (Unitarian) meeting house, located on Middle Street, was a wooden framed, clapboard-sheathed structure with a distinctive four-pointed neo-Gothic inspired tower. It was built in 1828, as the First Parish Church, replacing an earlier structure built on the site in 1738, when the "first" parish moved to the Harbor from its original location on the Annisquam River near where the Rte. 128 Grant Circle now is laid out. The parish system dated from the Massachusetts Bay Colony times, when both religious and civic business was conducted in the parish meetinghouses. This 1828 building was a descendant of that system. It became the Unitarian Church gradually in the 1830s, when more traditional members separated, formed their own society and built the Congregational/Trinitarian Church two doors to the west on Middle Street. The Universalists, Methodists, and Baptists had already seceded and formed their own congregations, and the parish system was at an end.

The Unitarian William Mountford, newly arrived from England, preached in this church from 1850 to 1853. In 1852, a new organ was dedicated on July 4, and Rev. Mountford was installed formally on August 3. (1) It is not known if Lane himself was a member of this or any church, but he shared several traits with Mountford: they both walked with a limp, and they were both interested in Spiritualism. Mountford moved to Boston in 1853 to pursue Transcendentalism and Spiritualism, and seldom returned to Gloucester. But he did come back in August, 1865, to officiate at Fitz Henry Lane's funeral, although Rev. Robert P. Rogers was minister at the time. It was from this church that Lane's body made its final journey to the Oak Grove Cemetery, where he was buried in the family plot of Joseph L. Stevens, Jr.

This building remained the Unitarian Church through the 1940s; however, the congregation had dwindled significantly and was no longer able to maintain the structure. The Gothic steeple was removed during this time. By 1950, the few remaining congregants were meeting with the Universalists further along Middle Street and the assets of the church were divided up: the church silver, made by Paul Revere, went to the Cape Ann Museum; endowment funds went to the Unitarian headquarters in Boston and the meeting house was sold to the local Jewish community who transformed it into Temple Ahavat Achim. Another victim of fire, it was destroyed in the conflagration that began in the next-door Lorraine Apartments on a wintry night of December, 2007.

Current Address: 86 Middle Street, site of Temple Ahavat Achim.

– Sarah Dunlap

Reference:

1. Babson, History of Gloucester, p. 497.

Watercolor on paper

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps »

Glass plate negative

Also filed under: Lane's Stone House, Duncan's Point » // Residences »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Procter Brothers »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

See p. 498. This shows the First Parish Meeting House before it was rebuilt in 1828.

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from top of Unitarian Church on Middle Street looking southeast, showing the Fort and Ten Pound Island. Tappan Block and Main Street buildings between Center and Hancock in foreground.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Ten Pound Island »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Middle Street looking west. At the corner of Dale Avenue is the Sanders-Davidson house, later Sawyer Free Library. Also shown: Unitarian Church, Congregational Church.

Also filed under: Sanders-Davidson House »

A grist windmill, originally owned by Ignatius Webber and then by Sidney Mason's father, John Mason, had stood on the hill since 1814, but, in preparation for the Pavilion Hotel, was moved to the inner-harbor side of the old Fort and eventually burned in 1877. Lot on which it stood by the water was sold to Sidney Mason in 1846. The windmill can be seen in several Lane harbor paintings and drawings.

Ignatius Webber’s windmill in its original location appears in View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 437) (far left, very small, with vanes), and View of Gloucester, (From Rocky Neck), 1846 (inv. 92) (also far left, a bit larger, but without vanes). After its move to Fort Point, it appears in the drawing of Gloucester Inner Harbor, (sitting on George H. Rogers’ Wharf), just behind the foremast of the two-masted New England boat), View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143). In the derivative painting owned by the Mariners’ Museum Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), this time it shows up just abaft the same boat’s main mast. The drawing and painting just show the building without vanes.

Lithograph

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–1835."

This section of the map shows the location of the Pavilion Hotel and ropewalk along the beach.

Also filed under: Maps » // Mason, John » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach » // Pavilion Hotel » // Ropewalk »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Through the years, this point and its fortifications had many names: Watch House Point, the Old Battery, Fort Defiance, Fort Head, and now just "The Fort." In 1793, Fort Defiance was turned over to the young United States government and was allowed to deteriorate. During the War of 1812 it was described as being "in ruins," and any remaining buildings burned in 1833. It was resuscitated in the Civil War and two batteries of guns were installed. The City of Gloucester did not regain ownership of the land until 1925.

The first fortifications on this point, guarding the entrance to the Inner Harbor, were put up in the 1740s, when fear of attack from the French led to the construction of a battery armed with twelve-pounder guns. Greater breastworks were thrown up in 1775, after Capt. Lindsay and his sloop-of-war the "Falcon" attacked the unprepared town. They were small and housed only a few cannon and local soldiers. Several other fortifications were at various times erected around the harbor: Fort Conant at what is now Stage Fort Park, another on Duncan's Point (near site of Lane's house) and the Civil War fort on Eastern Point. None of these preparations was ever called upon to actually defend the town.

Lane during his lifetime created a long series of images of the point and the condition of its fortifications. In 1832 there were still buildings standing, and the point had not yet been used for major wharves and warehouses. By the time of his painting Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), one can see that the earthwork foundation, but no superstructures, survived.

– Sarah Dunlap

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

Newsprint

Gloucester Telegraph

About picture of Old Fort hanging in the Gloucester Bank: "This picture is chiefly of interest on account of its preserving so accurately the features of a view so familiar to many of our citizens and which can never exist in reality."

Also filed under: Chronology » // Gloucester Bank » // Gloucester, Mass. – Gloucester Bank » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially useful in showing the Fort.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach » // Town / Public Landings »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

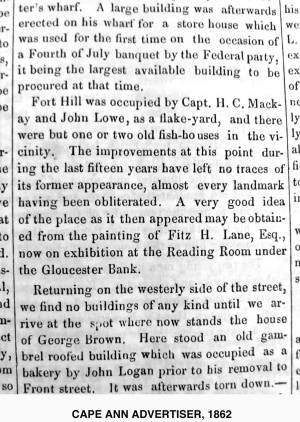

Newsprint

Cape Ann Advertiser

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Fort Hill was occupied by Capt. H. C. Mackay and John Lowe, as a flake-yard, and there were but one or two old fish-houses in the vicinity. The improvements at this point during the last fifteen years have left no traces of its former appearance, almost every landmark having been obliterated. A very good idea of the place as it then appeared may be obtained from the painting of Fitz H. Lane, Esq., now on exhibition at the Reading Room under the Gloucester Bank."

Also filed under: Gloucester Bank » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newspaper

Gloucester Telegraph

"By the will of the late Fitz H. Lane, Esq., his handsome painting of the Old Fort, Ten Pound Island, etc., now on exhibition at the rooms of the Gloucester Maritime Insurance Co., was given to the town... It will occupy its present position until the town has a suitable place to receive it."

Also filed under: Funeral & Burial » // Gloucester, Mass. – Marine Insurance Company » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Ten Pound Island »

Newsprint

Gloucester Telegraph

At the dedication of the Town House, speaker, "read the following letter:

To the Selectmen of Gloucester: / Gents: The will of our late Townsman, Fitz. H. Lane, contains this provision: / I give to the inhabitants of the Town of Gloucester, the picture of the Old Fort, to be kept as a memento[sic] of one of the localities of olden time; the said picture now hanging in the Reading Room under the Gloucester Bank, and to be there kept until the Town of Gloucester shall furnish a suitable and safe place to hang it. / The original sketch was taken twenty-five years ago, but the boats and vessels introduced are those of a quarter of a century earlier still. The painting was executed in 1859, six years before his decease."

Also filed under: Documents / Objects » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Town House »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from top of Unitarian Church on Middle Street looking southeast, showing the Fort and Ten Pound Island. Tappan Block and Main Street buildings between Center and Hancock in foreground.

Also filed under: Ten Pound Island » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

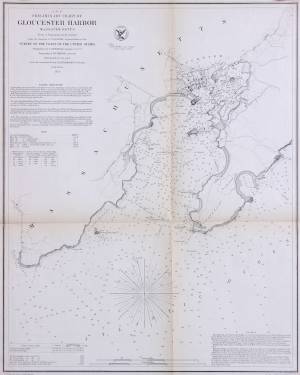

The northeast quarter of Gloucester Harbor is an inlet bounded by Fort Point and Rocky Neck at its entrance. It is further indented by three coves: Harbor Cove and Vincent’s Cove on its north side, and Smith’s Cove on its south side. The shallow northeast end is called Head of the Harbor. Collectively, this inlet with its coves and shallows is called Inner Harbor.

The entrance to Inner Harbor is a wide channel bounded by Fort Point and Duncan’s Point on its north side, and by Rocky Neck on its south side. From colonial times to the late nineteenth century, it was popularly known as “the Stream” and served as anchorage for deeply loaded vessels for “lightering” (partial off-loading). Subsequently it was known as “Deep Hole.”

Of Inner Harbor’s three coves, Harbor Cove (sometimes called “Old Harbor” in later years) was the deepest and most heavily used by fishing vessels in the Colonial Period, and largely dominated by the foreign trade in the first half of the nineteenth century. Its shallow bottom was the undoing of the foreign trade, as larger vessels became too deep to approach its wharves, and the cove returned to servicing a growing fishing fleet in the 1850s.

Vincent’s Cove, a smaller neighbor to Harbor Cove, was bare ground at low tide, and mostly useless for wharfage. Its shoreline was well suited for shipbuilding, and the cove was deep enough at high tide for launching. Records of shipbuilding there prior to the early 1860s have to date not been found.Smith’s Cove afforded wharfage for fishing vessels at its east entrance, as seen in Lane’s lithograph View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 86). The rest of the cove saw little use until the expansion of the fisheries after 1865.

The Head of the Harbor begins at the shallows surrounding Five Pound Island, extending to the harbor’s northeast end. Lane’s depiction of this area in Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23) shows the problems faced by vessel owners at low tide. Despite the absence of deep water, this area saw rapid development after 1865 when a thriving fishing industry needed waterfront facilities, even if they were accessible only at high tide.

– Erik Ronnberg

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

4 x 6 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Benham Collection

George Steele sail loft, William Jones spar yard, visible across harbor. Photograph is taken from high point on the Fort, overlooking business buildings on the Harbor Cove side.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Town House » // Universalist Church (Middle and Church Streets) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Lithograph

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Collins' and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Graving Beach »

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Dolliver's Neck » // Fresh Water Cove » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Maps »

41 x 29 inches

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives

Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Collins's, William (estate wharf) » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

Photograph in The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, published by N. L. Stebbins, Boston

Also filed under: Beacons / Monuments / Spindles »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

From East Gloucester looking towards Gloucester.

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stereo view showing Gloucester Harbor after a heavy snowfall

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Five Pound Island and Gloucester inner harbor taken from the top of Hammond Street building signs in foreground are for Severance, Carpenter and Crane, and Cooper at Clay Cove.

Also filed under: Five Pound Island »

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Schooner (Fishing) »

Oil on canvas

34 x 45 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Mrs. Jane Parker Stacy (Mrs. George O. Stacy),1948 (1289.1a)

Detail of party boat.

Also filed under: Party Boat »

Glass plate negative

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Detail from CAHA#00279

The magnificent views of Gloucester Harbor and the islands from the top floor of the stone house at Duncan's Point where Lane had his studio were the inspiration for many of his paintings.

From Buck and Dunlop, Fitz Henry Lane: Family, and Friends, pp. 59–74.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Lane's Stone House, Duncan's Point » // Residences »

Glass plate negative

3 x 4 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

#10112

Also filed under: Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860)

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

Rocky Neck lies on the eastern side of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor and along with Ten Pound Island provides a vital block to the southerly and westerly seas running down the Outer Harbor. Called Peter Mud’s Neck in the late 1600s, it was an island at high tide until the 1830s, reachable only by walking over the sand bar connecting it to the mainland at low tide. When the stone causeway was put in in the 1830s it not only made the Rocky Neck a functional neighborhood of East Gloucester, it secured the southwest end of Smith’s Cove against swell from the Outer Harbor and made the cove a tight and secure anchorage.

In Lane’s time it was primarily sheep pasture with a small population living on the fringes. In 1859 a marine railway was built at the end of the neck which is still in operation. As a result of Gloucester’s burgeoning fish trade, wharves and fish businesses quickly sprang up along the shore of the newly secure Smith’s Cove. In 1863 another landmark Gloucester business, the marine antifouling copper paint manufactory of Tarr and Wonson was built on the western tip. The Hopper-esque dark red building still stands and guards the entrance to the Inner Harbor directly across from Fort Point.

Lane drew the view for his second and third Gloucester lithographs from Rocky Neck looking across to the Inner Harbor to the town. He also did a major painting Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14) which shows the sheep, shepherd and dog on the rocky pasture in the foreground with the busy harbor and town unfolding before them.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Rocky Neck became an active waterfront neighborhood with a row of grand houses on its spine overlooking the harbor and town. Edward Hopper painted one of the more spectacular Beaux Arts houses on that ridge, the afternoon light catching its extraordinary trim and mansard roof, still beautifully preserved today.

Rocky Neck is perhaps best known today as Gloucester’s, and arguably America’s, most famous art colony. Beginning in the 1880’s and extending through the 1970’s, multiple generations of artists, including Homer, Duveneck, Hopper, Sloan, Twachtman and many others, representing every artistic style, have summered and worked, socialized and relaxed in the quaint and once ramshackle confines of the Neck.

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Newspaper clipping in "Authors and Artists "scrapbook

p.42

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This painting was considered by far the best of the several paintings by Fitz H. Lane and was a view of Gloucester from Rocky Neck at the time Mr. Lane painted it in 1856. From this painting Mr. Lane had finished a number of lithographs which were sold at a very low price. This did not bring to Mr. Lane much ready money and he was somewhat disappointed so he mounted several of these on canvas, painted them in oil and sold them to several of his friends for $25 and there are a number of these at present held in Gloucester and valued very highly.

The original painting was given to the town about the time the new town house was built and was put on the wall back of the stage in the large hall. When the building was found to be on fire it was impossible to get into the big hall to save anything and so this picture was destroyed. It was a genuine regret that this happened because of its historic value and being considered as the best work that Mr. Lane had done. A study of the pictures finished by Mr. Lane from this original is very interesting and particularly by reason of the type of fishing vessel and shipping in the harbor. In the foreground of the painting is a fine type of the Surinamers of those days which sailed out of Gloucester and brought wealth to many Gloucester families.

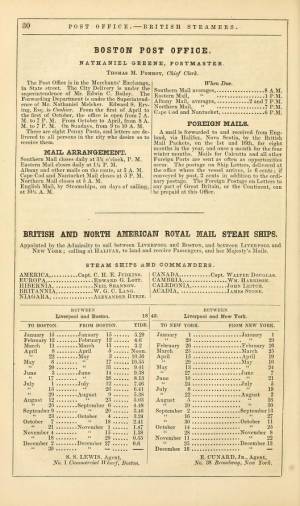

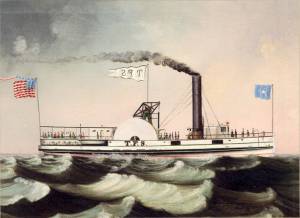

The first attempt to establish steamboat service between Gloucester and Boston came in 1846 when Menemon Sanford placed the steamboat "Yacht" on irregular passages between the two ports. "Yacht" was built at New York, New York in 1844, but her activity prior to coming to Gloucester is not known at this time, nor is her history after 1848, when another steamboat was put into service. "Yacht's" registry dimensions were: length 140 feet, breadth 22.5 feet, depth 8.3 feet, registered tonnage 249.64. These figures are average for the Boston–Gloucester steamboats prior to 1860.

Published sources place "Yacht's" first year of service at "about 1847," but Gloucester newspaper announcements in the previous year make it clear that she was serving Boston and Gloucester in 1846.

– Erik Ronnberg

Reference:

1. Charles Rodney Pittee, "The Gloucester Steamboats," The American Neptune, October 1952, 288–93.2.

Hermaphrodite brigs—more commonly called half-brigs by American seamen and merchants—were square-rigged only on the fore mast, the main mast being rigged with a spanker and a gaff-topsail. Staysails were often set between the fore and main masts, there being no gaff-rigged sail on the fore mast. (1)

The half-brig was the most common brig type used in the coasting trade and appears often in Lane’s coastal and harbor scenes. The type was further identified by the cargo it carried, if it was conspicuously limited to a specialized trade. Lumber brigs (see Shipping in Down East Waters, 1854 (inv. 212) and View of Southwest Harbor, Maine: Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 260)) and hay brigs (see Lighthouse at Camden, Maine, 1851 (inv. 320)) were recognizable by their conspicuous deck loads. Whaling brigs were easily distinguished by their whaleboats carried on side davits (see Ships in the Harbor (not published)). (2)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. M.H. Parry, et al., Aaak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 268, 274; and A Naval Encyclopaedia (L.R. Hamersly & Co., 1884. Reprint: Detroit, MI: Gale Research Company, 1971), 93, under "Brig-schooner."

2. W.H. Bunting, An Eye for the Coast (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House: 1998), 52–54, 68–69; and W.H. Bunting, A Day's Work, part 1 (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House: 1997), 52.

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) oncargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Fishing Schooners: While the port of Gloucester is synonymous with fishing and the schooner rig, Lane depicted only a few examples of fishing schooners in a Gloucester setting. Lane’s early years coincided with the preeminence of Gloucester’s foreign trade, which dominated the harbor while fishing was carried on from other Cape Ann communities under far less prosperous conditions than later. Only by the early 1850s was there a re-ascendency of the fishing industry in Gloucester Harbor, documented in a few of Lane’s paintings and lithographs. Depictions of fishing schooners at sea and at work are likewise few. Only A Smart Blow, c.1856 (inv. 9), showing cod fishing on Georges Bank (4), and At the Fishing Grounds, 1851 (inv. 276), showing mackerel jigging on Georges Bank, are known examples. (5)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 74–76.

5. Howard I. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 58–75, 76–101.

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

Stereograph card

Frank Rowell, Publisher

stereo image, "x " on card, "x"

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View showing a sharpshooter fishing schooner, circa 1850. Note the stern davits for a yawl boat, which is being towed astern in this view.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Model made for marine artist Thomas M. Hoyne

scale: 3/8" = 1'

Thomas M. Hoyne Collection, Mystic Seaport, Conn.

While this model was built to represent a typical Marblehead fishing schooner of the early nineteenth century, it has the basic characteristics of other banks fishing schooners of that region and period: a sharper bow below the waterline and a generally more sea-kindly hull form, a high quarter deck, and a yawl-boat on stern davits.

The simple schooner rig could be fitted with a fore topmast and square topsail for making winter trading voyages to the West Indies. The yawl boat was often put ashore and a "moses boat" shipped on the stern davits for bringing barrels of rum and molasses from a beach to the schooner.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seafarers in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 29–31.

Also filed under: Hand-lining » // Ship Models »

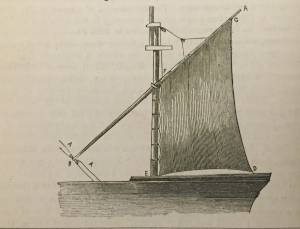

20 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

The image, as originally drafted, showed only spars and sail outlines with dimensions, and an approximate deck line. The hull is a complete overdrawing, in fine pencil lines with varied shading, all agreeing closely with Lane's drawing style and depiction of water. Fishing schooners very similar to this one can be seen in his painting /entry:240/.

– Erik Ronnberg

Newspaper

"Shipping Intelligence: Port of Gloucester"

"Fishermen . . . The T. [Tasso] was considerably injured by coming in contact with brig Deposite, at Salem . . ."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newsprint

From bound volume owned by publisher Francis Procter

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

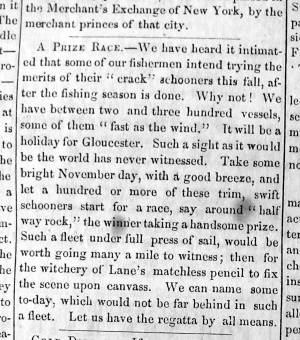

"A Prize Race—We have heard it intimated that some of our fishermen intend trying the merits of their "crack" schooners this fall, after the fishing season is done. Why not! . . .Such a fleet under full press of sail, would be worth going many a mile to witness; then for the witchery of Lane's matchless pencil to fix the scene upon canvass. . ."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Also filed under: Cape Ann Advertiser Masthead »

Stereograph card

Procter Brothers, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Rocky Neck » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

See p. 254.

As Erik Ronnberg has noted, Lane's engraving follows closely the French publication, Jal's "Glossaire Nautique" of 1848.

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester »

Wood, cordage, acrylic paste, metal

~40 in. x 30 in.

Erik Ronnberg

Model shows mast of fishing vessel being unstepped.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Fishing »

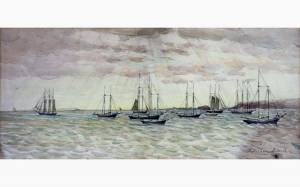

Watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 19 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Rev. and Mrs. A. A. Madsen, 1950

Accession # 1468

Fishing schooners in Gloucester's outer harbor, probably riding out bad weather.

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer »

Photograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Print from bound volume of Gloucester scenes sent to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

11 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

Schooner "Grace L. Fears" at David A. Story Yard in Vincent's Cove.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Shipbuilding / Repair » // Vincent's Cove »

The term "ship," as used by nineteenth-century merchants and seamen, referred to a large three-masted sailing vessel which was square-rigged on all three masts. (1) In that same period, sailing warships of the largest classes were also called ships, or more formally, ships of the line, their size qualifying them to engage the enemy in a line of battle. (2) In the second half of the nineteenth century, as sailing vessels were replaced by engine-powered vessels, the term ship was applied to any large vessel, regardless of propulsion or use. (3)

Ships were often further defined by their specialized uses or modifications, clipper ships and packet ships being the most noted examples. Built for speed, clipper ships were employed in carrying high-value or perishable goods over long distances. (4) Lane painted formal portraits of clipper ships for their owners, as well as generic examples for his port paintings. (5)

Packet ships were designed for carrying capacity which required some sacrifice in speed while still being able to make scheduled passages within a reasonable time frame between regular destinations. In the packet trade with European ports, mail, passengers, and bulk cargos such as cotton, textiles, and farm produce made the eastward passages. Mail, passengers (usually in much larger numbers), and finished wares were the usual cargos for return trips. (6) Lane depicted these vessels in portraits for their owners, and in his port scenes of Boston and New York Harbors.

Ships in specific trades were often identified by their cargos: salt ships which brought salt to Gloucester for curing dried fish; tea clippers in the China Trade; coffee ships in the West Indies and South American trades, and cotton ships bringing cotton to mills in New England or to European ports. Some trades were identified by the special destination of a ship’s regular voyages; hence Gloucester vessels in the trade with Surinam were identified as Surinam ships (or barks, or brigs, depending on their rigs). In Lane’s Gloucester Harbor scenes, there are likely (though not identifiable) examples of Surinam ships, but only the ship "California" in his depiction of the Burnham marine railway in Gloucester (see Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, 1857 (inv. 29)) is so identified. (7)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. R[ichard)] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman’s Friend, 13th ed. (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1873), p. 121 and Plate IV with captions.

2. A Naval Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884), 739, 741.

3. M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World’s Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 536.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 281–87.

5. Ibid.

6. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 26–30.

7. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 67–69.

Photograph

From American Clipper Ships 1833–1858, by Octavius T. Howe and Frederick C. Matthews, vol. 1 (Salem, MA: Marine Research Society, 1926).

Photo caption reads: "'Golden State' 1363 tons, built at New York, in 1852. From a photograph showing her in dock at Quebec in 1884."

Also filed under: "Golden State" (Clipper Ship) »

Oil on canvas

24 x 35 in.

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

Walters' painting depicts the "Nonantum" homeward bound for Boston from Liverpool in 1842. The paddle-steamer is one of the four Clyde-built Britannia-class vessels, of which one is visible crossing in the opposite direction.

View related Fitz Henry Lane catalog entries (2) »

Also filed under: Packet Shipping » // Walters, Samuel »